Alpha Wolfe

You should skip "A Man in Full" and watch the first film adaptation of Tom Wolfe's work. PLUS: A complete guide to the writer's onscreen oeuvre

The Netflix adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s 1998 novel A Man in Full was released last week. A lot of people are probably wondering why David E. Kelly and Regina King felt that this late-career work that marked the decline of a once-great writer deserved an eight-episode adaptation in the year 2024. I am certainly wondering that. (So are many critics.)

The book is about a boorish over-leveraged billionaire whose twin obsessions are hanging onto his fortune and projecting an image of swaggering masculinity. I suppose that has some Trump resonances... But the critical reception of the novel wasn’t much better than the reaction to the new miniseries. When it was released in the late 1990s, it was widely seen as evidence that the firm grip on the zeitgeist that Wolfe had exhibited over the previous three decades was slipping.

No one reading A Man in Full without any prior knowledge of Wolfe could possibly grasp why each his earlier works—fiction or non-fiction—became a cause célèbre or succès de scandale, sparking endless debates and often setting off bidding wars for film and TV rights.

Wolfe was one of the key figures who introduced the literary techniques of fiction to feature writing. He also had an uncanny knack for spotting the most interesting developments in pop culture, youth culture, and counterculture. He coined incisive and witty neologisms that instantly entered the national consciousness: The Me Generation, radical chic, the Masters of the Universe… He was like a superhero to many, and like any true superhero, he had an instantly recognizable uniform: white suit and rakishly tilted homburg hat, sometimes accentuated with an honest-to-god cape.

The 2023 documentary Radical Wolfe gives a sense of just how influential and impactful the writer was in his prime. It’s available to stream on Netflix.

I watched a little bit of A Man in Full on Netflix, and…I doubt I will ever finish it. But the new series spurred a deep dive into previous film and TV adaptations of Wolfe’s work. Below I submit an appreciation of a woefully overlooked 1973 film based on one of his most memorable magazine pieces. I also drew up a list of all the other adaptations that have been made, including info on a few documentaries and weird obscurities that might be of interest to people who admire Wolfe—did you know that there’s an opera based on The Bonfire of the Vanities, and you can stream it for free on Tubi?! (Wherever possible, I’ve included details on how you can watch all of this stuff.)

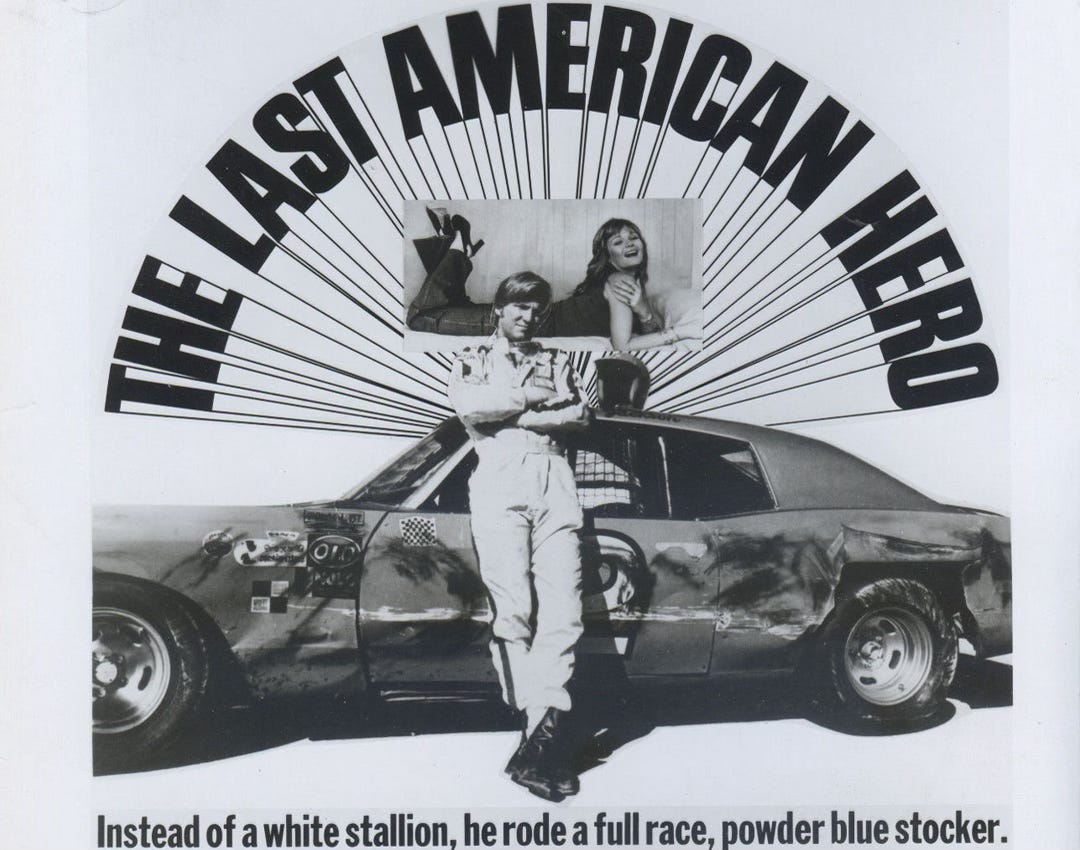

”The Last American Hero is Junior Johnson. Yes!” (1963) adapted as The Last American Hero (1973)

Wolfe's 1965 Esquire feature about stock car racing champion Junior Johnson was an epochal example of what would come to be known as New Journalism. Wolfe vividly captured the thrilling intensity of NASCAR competitions and the reserved swagger of Johnson, who learned to race by shaking off the cops while running shipments of his father’s moonshine. But what sticks with you is the evocative portrait Wolfe paints of the North Carolina milieu.

The subjects of his feature probably saw the writer as a dandified city slicker from way up north in Richmond, Virginia. But Wolfe saw himself as a fellow Southerner, and he wanted to present an uncondescending view of the region and its culture to the stuffy, snobbish Northern establishment that subscribed to (and published) Esquire. He nails the details of the environs, the rhythms of the people’s lives, and the cadence of their speech. The writer doesn’t simply note that Junior Johnson and his father and all of their fellow moonshine runners were folk heroes in their community; he traces the origins of that adulation back to the Whiskey Rebellion in the 18th century.

The essay is where many Americans first learned of the phrase “good ol’ boy,” and Wolfe explains its meaning with great rigor and precision. Junior Johnson was given to communicating in monosyllabic grunts but was also capable of surprising eloquence and self-awareness. Wolfe renders Johnson’s voice so authentically that I found myself repeatedly wondering how he did it—was he taking shorthand notes, or using some sort of recording device, or channeling Johnson’s voice himself (and bending the rules of journalism a tad)?

Wolfe’s feature was adapted into the 1973 film The Last American Hero. It’s not quite as earth-shattering as its source material, but it’s one of the great car-centric films of the early 1970s, and that’s really saying something. I mean, this is the era that gave us The French Connection, American Graffiti, Le Mans, Vanishing Point, Duel, Two-Lane Blacktop, Gone in 60 Seconds, The Seven-Ups, Sugarland Express…

The racing scenes are shot and edited with grit and verisimilitude, bringing you into the action at race tracks, demolition derbies, or on dirt roads. The whole cast is great, but Jeff Bridges is fantastic as Johnson. The locations and cinematography do a good job of capturing the flavor of the locale, though sticklers for historical authenticity will grumble about how the extras in a film set in the mid-1950s have bushy sideburns and long pointy shirt collars. (The fact that the theme song happens to be that quintessential 1970s chestnut “I Got a Name” by Jim Croce is also a jarring anachronism. It debuted in the film several months before it became a radio hit.)

The film helped forge the cinematic paradigm of sexy rebellious downhome dudes sticking it to The Man on the open roads. It set the pattern for all of the Southsploitation flicks that dominated grindhouses in the 1970s, which often focused on outmaneuvering the fuzz via badass stunt driving and a bleeding-edge communication tool known as Citizens band radio. The subgenre would reach its zenith with Smokey and the Bandit, and we can also credit/blame it for The Dukes of Hazard.

The inimitable New Yorker critic Pauline Kael really admired the film, writing "With a script that uses Wolfe as the source for most of the story elements, Lamont Johnson, who directed, has done the Southern racing scene and the character of the people caught up in it better, perhaps, than they’ve ever been done before." But she faulted it for tacking on a fictionalized downbeat ending in classic 1970s fashion—the film creates an arc where the rebel Johnson is forced to kowtow to the forces of capital to get his shot. In real life, Johnson told Wolfe that a short stint in prison for illicit distilling taught him that following rules and doing what he was told wouldn’t kill him. But he was able to rise to the top of his sport without making the sort of devil’s bargain that the film portrays.

Kael’s review is excellent, of course, and worth reading in full. She’s especially insightful about the car’s place in cinema and Wolfe’s place in journalism. This bit is particularly good: “Wolfe used the youth culture for excitement just as the movies did. Movies hit us in more ways than we can ever quite add up, and that’s the kind of experience that Tom Wolfe tried to convey in prose.” The Last American Hero (1973) is available to rent or buy on Prime and Youtube.)

The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (1965)

Studios have always been quick to option many of Wolfe's trailblazing nonfiction works. His first book-length collection of magazine pieces was a best seller that sparked a lot of interest from film studios, especially the anchor story that gives the book its name. It’s a deep dive into the subculture of custom car aficionados in California, but the original version that ran in Esquire in 1963 had a much more fulsome and Wolfe-ian title, loaded with exclamation points and onomatopoeia: "There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy-Kolored (Thphhhhhh!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (Rahghhh!) Around the Bend (Brummmmmmmmmmmmmmm)…"

The story established Wolfe’s ongoing fascination with subcultural icons. He clearly admires and envies the custom car artists George Barris and Ed “Big Daddy” Roth because they are completely divorced from the sophisticated art world, and they because they never attempted to move beyond the teen culture they emerged from—they are “untouched by the big amoeba god of Anglo-European sophistication that gets you in the East.” That amoeba got its grubby hands all over Wolfe, and he uses his classical education to put the creations of these hot rod artists in terms that all of the square magazine readers could understand. He compares Roth’s creations to works by Salvador Dali and Heironymous Bosch and lays out a framework in which custom car culture is the Dionysian antithesis to the orderly Apollonian designs of Detroit and the Big Three.

The film adaptation of “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby” was to be directed by John Boorman, but it never happened. However, Wolfe did eventually appear in a documentary on the legacy of the hot rod artiste Roth. The film is called Tales of the Rat Fink, and it's available for rent or purchase on Prime. Some miscreant posted a bootleg of the entire film on YouTube, and here is the portion that features Wolfe.

In keeping with the car-crazy theme of this documentary about Ed "Big Daddy" Roth and his kustom kreations, all of the interviewees appear to speak through their vehicles. Wolfe’s disembodied voice emerges from his 2003 Cadillac Seville. (Both the writer and the car are clad in all-white, natch.)

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968)

Wolfe's book about Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, who lived communally and traveled across the country evangelizing for LSD, was a huge hit that cemented the image of hippie culture and psychedelia in the public imagination. The film rights for the book were optioned, but an adaptation was never made. However, the footage that the pranksters themselves shot of their own exploits while Wolfe was reporting on them was later incorporated into the 2011 documentary Magic Trip: Ken Kesey's Search for a Kool Place. It’s currently free to stream on Prime.

Tom Wolfe's Los Angeles (1977)

The great lost artifact of the writer's onscreen career is this made-for-TV special that he penned and hosted for PBS. It's supposedly a freewheeling and episodic satire of Tinseltown that covers some of the same territory as his 1970 essay "Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers," which mocked minority resentment as well as the guilt of do-gooder white liberals. That’s a theme running through a lot of the writer’s post-1960s work, which, to put it mildly, has not aged well. He probably saw it as sticking it to the cliches of the liberal establishment—not racism, per se, but anti-anti-racism. It rarely comes off that way.

Wolfe appears as himself and narrates the proceedings. The New York Times reviewer found the satire to be juvenile, noting that it's "as subtle as a porno flick" and that "Mr. Wolfe's snickering television essay becomes an intolerable exercise in contempt." It sounds tasteless and offensive and kind of crummy, and that somehow makes me want to see it even more. Unfortunately, all that's available on the interwebs is some raw outtake footage

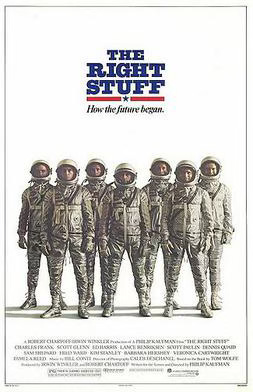

The Right Stuff (1979) adapted as The Right Stuff (1983) and The Right Stuff (2020)

The nonfiction novel was the culmination of seven years of reporting and research on NASA and the Mercury 7 astronauts. It became Wolfe’s best-selling work to that date, won the National Book Award, and is widely regarded as one of the great works of literary non-fiction. The film adaptation won four technical Oscars and deserved to win several more. Everyone loved it except for the original screenwriter William Goldman and the astronauts themselves, who all felt that it portrayed the Mercury 7 men as little more than “spam in a can.”

This is one of those movies of the era like Diner or The Outsiders that features a cast full of relative unknowns who would all go on to great fame and success. It’s filmmaker Phil Kaufman’s masterpiece—which is saying something since he’s the guy who directed The Outlaw Josey Wales, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and Henry & June. It’s available to rent or buy for a nominal fee from numerous sources online.

In 2020, National Geographic released a limited series adaptation of both the book and the film. Unlike the movie, it didn’t focus on the contrast between the mediagenic, college-educated Mercury 7 astronauts and laconic, hard-bitten test pilot Chuck Yeager. The series is rather dull and dutiful, and it received a chilly reception. A planned second season was canceled, and it was removed from the Disney+ streaming service in a belt-tightening move.

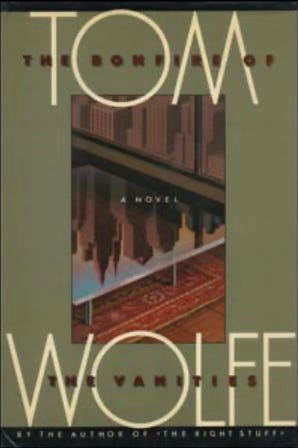

The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987) adapted as The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) and The Bonfire of the Vanities (2015)

Wolfe’s first major foray into fiction was a sensation and a bestseller that was widely regarded as a quintessential novel of the 1980s. The film adaptation featured a screenplay by Pulitzer and Tony Award-winning playwright Michael Christofer, production design by Oscar-winner Richard Sylbert, direction by an auteur at the apex of his box office clout, and performances by several high-profile actors who were on the cusp of a new level of success and critical acclaim. The result is…

Look, I am a huge fan of Brian DePalma. I will talk your ear off about the merits of even his lesser works like The Fury and Phantom of the Paradise and Hi, Mom! But he was the worst possible choice to direct this film, and none of his signature cinematic flourishes do more than temporarily distract from the thudding unsubtlety of this unfunny satire.

There’s exactly one memorable scene, where the nervousness of the protagonist gradually turns a routine police interview into a suspect interrogation. But everything else in this cack-handed production serves to magnify the flaws that were already there in Wolfe’s jaundiced take on a modern multicultural metropolis. It’s become one of those films like Heaven’s Gate or Ishtar or Waterworld where its scandalous commercial failure has completely overshadowed the work itself, and while some stick up for the merits of those other movies, no one can muster a defense of this one. It’s available to rent or buy from multiple sources online, but don’t.

Turner Classic Movies devoted a whole season of their podcast The Plot Thickens to the behind-the-scenes story of what all went wrong with the Bonfire adaptation. It was based on Julie Salamon's excellent, dishy book The Devil's Candy, and Salomon hosted that season of the podcast.

The opera adaptation [?!] of Bonfire of the Vanities is currently free with ads on Tubi. (Come back, Brian DePalma, all is forgiven!) The opera's website is still online even though it closed after its initial performances nine years ago.

Miscellany

Wolfe’s later work descended into self-parody, with increasingly crotchety and obtuse attacks on topics from college promiscuity to Darwinism. But he also parodied himself with characteristic elan in the 6th season Simpsons episode "Moe'N'a Lisa"—that's available on Disney Plus.

Wolfe also made a cameo as himself in Bill Cosby's short-lived final TV series in 1999, but that has [understandably] been memory-holed.

The lower half of Wolfe's body makes an appearance in the avant-garde film by Yoko Ono and John Lennon, Up Your Legs Forever. It's literally just a feature-length assemblage of footage of various people's legs, capped by a shot of the filmmaking duo's buttocks. It isn't available to stream anywhere, and honestly, I'm not losing much sleep over that fact.