Before the Humane AI Pin, There Was the Power Glove

The 2024 virtual assistant and the 1989 wearable controller both promised a radical new form of interactivity. One problem: neither actually worked

One year ago this month, the Humane AI Pin was launched to much fanfare. The revolutionary device promised to be a real-life version of the smart devices that were central characters in the 2013 Spike Jonez sci-fi romance Her. The Pin is a tiny two-ounce square, about the size of an Apple Watch sans band, that can be clipped to your belt or shirt pocket. There’s no screen of any kind to tap out messages on—you interact with it through speech, gestures, or even by holding up objects to it for recognition.

The Pin promised to forever change how we thought of mobile devices. There was one problem, though: it just flat-out didn’t work. This February, Humane was sold to HP for less than half of the funding it raised to create the device, and announced that support for the Pin would end.

The new era of interactivity that the Humane Pin promised to usher in lasted less than a year. I come not to gloat over its untimely demise—I’m rooting for any bold innovator who dares to design a completely new type of human-computer interface. The failure of this product is a reminder of just how hard it is to design and mass-produce such a thing.

All of this put me in mind of another massively hyped device that promised to fundamentally change how we interacted with technology…if it had only worked. It was called the Mattel Power Glove.

Most people first got a glimpse of the Power Glove in the 1989 film The Wizard, which was about kids traveling across the country to take part in a video game tournament. The whole film is a thinly veiled commercial for Nintendo, but the reveal of the Power Glove is a particularly egregious example of diegetic advertising. A cool kid sporting Ray Bans produces a gleaming silver case and opens it to reveal what looks like a prop from a sci-fi movie.

It's a bulky metallic grey glove with input devices attached to the knuckles and the wrist. It bristles with controller buttons. An ersatz version of Morricone's The Good the Bad and the Ugly theme song plays as the kid straps it on, flexing his fingers and holding his arm aloft like he's wearing Marvel’s Infinity Gauntlet.

The kid fires up the game Rad Racer on his Nintendo Entertainment System game console and begins to play, holding his gloved hand out in front of him as if it were wrapped around an invisible steering wheel. With simple and natural twists of his wrist, he weaves the car in Rad Racer between lanes with the casual cool of Magnum P.I. piloting his cherry red Ferrari down the Moanalua Freeway. “I love the Power Glove,” he effuses. “It's so bad.”

Mattel's other commercial for the device—the one that ran on TV, not that scene from The Wizard—followed the same paradigm, depicting a cool young dude in a denim jacket waving his hand around like an orchestra conductor to play classic Nintendo games. With a flick of his wrist, he can make Mario jump in Super Mario Bros. 2. Then he uses the glove to make the boxer Little Mac sock his opponents in Punch-Out. The narrator intones, “Now you and the games are one.”

It’s so bad

This wearable device promised a radical new form of interface that was as natural and intuitive as turning a door handle. It was based on The Dataglove developed by VPL Research, a company that was at the forefront of the first VR boom in the 1980s. “Optical fiber sensors mounted on a lightweight lycra glove monitor flexion and extension of the fingers,” reads the promotional material, “while a magnetic sensor measures the position and orientation of the hand.”

When attached to a cutting-edge computer of the era, the Dataglove could detect subtle movements of the fingers in three dimensions. “The glove lets you feel a world that doesn’t exist as if it’s real and pick up things in that world as if they’re real,” said VPL Research’s dreadlocked founder Jaron Lanier. “It lets you reach into an imaginary world.”

The toy company Mattel licensed VPL’s technology. Then they set out to make something that could be mass-produced much more cheaply than the Dataglove, and marketed to kids as a cool new way to play games. Instead of requiring a personal computer, it would be designed to work with the far less powerful Nintendo Entertainment System game console.

But something vital was lost in that downgrade. The kid in that movie The Wizard who said that the Power Glove was “so bad” used the phrase in the Run DMC sense — not bad meaning bad, but bad meaning good. But in point of fact, the traditional definition of “bad” was far more accurate. The Power Glove simply did not work as advertised.

Kids who were seduced by The Wizard into begging their parents for the Mattel controller quickly discovered that it was impossible to play that cool-looking racing game Rad Racer, or any other classic NES game, using the $75 (about $190 in today's money) glove.

The Mattel Power Glove was a legendary failure. Like the Humane AI Pin, it was discontinued after less than a year on the market. Looking at the two devices, a few key lessons emerge for anyone hoping to sink tens of millions of dollars into establishing a new UX:

Technical limitations - Both products suffered from technology that wasn't a match for their ambitions. New interfaces need technical foundations that can deliver on their promises.

No clear value proposition - Neither product effectively answered the question "What problem does this solve better than existing solutions?"

Just because a new form of interactivity looks cool in a carefully edited promotional video doesn’t mean people won’t find it to be a chore when the novelty wears off - The social awkwardness of the AI Pin's interactions and the impracticality of wearing the Power Glove quickly became apparent to users. Think about the glove-based interface that Tom Cruise shows off at the beginning of the sci-fi film Minority Report. It looks cool, but would you really want to stand in front of an array of screens for your entire work day waving your arms around like an air traffic controller?

Refusing to Let Go

Despite its quick commercial flameout, the Power Glove still has plenty of ardent defenders. “It was not just a gimmicky toy,” insists Andrew Austin, one of the directors of the documentary The Power of Glove, which explores the failed promise of the device.

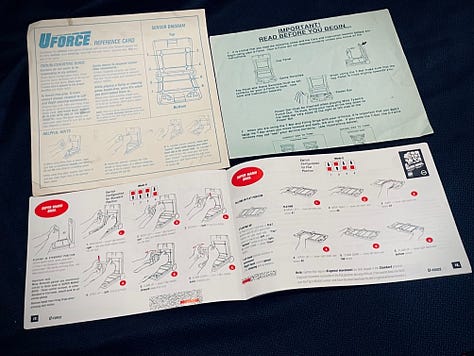

He explains that it’s an oversimplification to say that the device did not work. “It was using the speed of sound to triangulate its position,” Austin explains. “Two transmitters in the glove were 'chirping' at three receivers that you placed on your TV. It was very sophisticated, but the cycle could only happen 20 times a second, which is three times slower than a regular Nintendo controller. If you have a game designed for quick tactile response, something that requires catlike reflexes, then the Power Glove is operating at a big disadvantage.”

“You just can't play Super Mario with a motion controller,” says Adam Ward, another director of The Power of Glove. “It's just not conducive to capturing the small movements you need to make in order to control Mario.”

Ward insists that games that were designed around the slower response time of the controller worked just fine. “Mattel did have a lineup of custom games slated to come out for it. Super Glove Ball was the only one released, and it plays fairly well – you can actually sense your hand moving in this virtual 3D space.”

There was another game called Bad Street Brawler that had Power Glove support retrofitted onto it. But because the game wasn’t designed with the controller in mind, it was an excruciating struggle to control the onscreen action of the protagonist, “Duke Davis. Former International Punk Music Rocker and Street Fighter Extraordinaire.” None of the other planned releases in the Power Glove Gaming Series made it to market before the device was discontinued.

There were an array of weird gesture-based controllers in the offing, and Mattel was eager to beat potential rivals, like the “touch-free” Broderbund U-Force controller, to market. “They rushed it, in a nutshell,” says Austin. The Power Glove went from concept to commercial release in about a year, and man oh man did it show.

The device made a promise that no peripheral available at Toys R Us could hope to keep. Still, it looked like what the Nintendo Generation saw in their mind's eye when they imagined the future. “We talked to the designers of the device, and they said that they wanted children to think this was a very expensive high-tech piece of wearable electronics,” says Austin. “The awesome little input device on the top is called ‘The Stealth,’ and it was modeled after Robocop.”

“Even the bulkiness of it was a selling point,” adds Ward “This was the era of giant mobile phones, giant shoulder pads, and big hair. Everything was big back then.”

“Nowadays, we want tech to be sleek and almost invisible,” notes Austin. “Back then, they wanted to make you look like a cyborg. There was this almost delusional sense of tech optimism.”

Endless Glove

The Power Glove sold a very specific fantasy that it had no hope of realizing. But Mattel’s short-lived controller has had a bizarre afterlife as an iconic example of consumer-grade retrofuturism and Reagan-era kitsch. The device seems to embody all of the gee-whiz techno-utopianism that burned within the hearts of Eighties kids. Long after the glove was pulled from the market, it lived on as a pop culture icon.

In the 1991 film Freddy's Dead: The Final Nightmare, the titular serial killer upgrades his bladed weapon to have Power Glove functionality. The controller also made cameos in everything from the family movie Beethoven to the film that made it impossible to ever take the notion of “cyberpunk” seriously: Hackers.

Mattel's peripheral is still a pop culture icon, though now it's more likely to signify nostalgia and quaintly dated retrofuturism. The Regular Show on the Cartoon Network built a whole episode around something called the Maximum Glove, a cool-looking controller that failed to do what the commercials promised.

In the kitschy retro-futurist movie Kung Fury, the Power Glove is an essential tool that the character Hackerman needs to time travel, and its kitschy cameo lovingly mimics its debut moment in The Wizard. In the 2021 film 8-Bit Christmas, the 1940s setting of A Christmas Story is updated to the 1980s, and the Power Glove is employed as the central MacGuffin, just like the Red Ryder BB Gun in the original film.

“The Power Glove is such a potent reminder of how the 1980s embraced technology with excitement and optimism,” says Ward. “The people making it weren’t trying to ruin everybody’s Christmas in 1989; they were genuinely trying to make an awesome toy and push the limits of consumer technology while doing it.”

People continue to do things with (and for) the Power Glove. There’s a thriving indie game development scene for the original Nintendo console, including homebrew Power Glove games like 8-Bit Hero Trainer, a “first-person combat simulator for training to fight 8-bit RPG-style monsters.”

Many people were so besotted with with promise of the Power Glove that they redesigned it to do all of the amazing things that they felt it was capable of. For instance, Dillon Markey, a filmmaker working on shows like Robot Chicken, turned his glove into a Bluetooth-enabled software controller that lets him tap the buttons on his wrist to shuffle back and forth between frames in his stop-motion animation software while shooting. (He also added a touch-sensitive microphone so that when he gives you a fist bump, his glove says “FU¢#!NG AWESOME!”)

Yeuda Ben-Atar, who goes by the handle Side Brain, mapped the buttons and fingers of the glove to MIDI effects, so he can perform live shows by waving around the Mattel controller. It also has a retractable set of tweezers for making minute adjustments to his character models

And Alessio Cosenza, an IT professional from Italy, retrofitted the glove to make it a fully functional VR controller. His mod, which he dubs the Power Glove Ultra, can actually do everything that the ads for the Power Glove promised. “It features almost 50% of the original hardware and some basic off-the-shelf electronic components,” Cosenza tells me.

Watching Cosenza's video demoing his retrofitted Power Glove, it becomes even more clear that the device anticipated the Nintendo Wiimote and the motion controllers for VR devices like the HTC Vive and the Meta Quest. “It was absolutely ahead of its time, even if it didn't work!” Cosenza insists. “I mean, the idea, the look, the overall concept…in 1989!?”

ELSEWHERE: Watch the documentary The Power of Glove, which is available on several streaming services. The filmmakers encourage you to watch it “if you’re into reminiscing about a happier time when technology actually seemed cool instead of evil.”

The Retroist did a podcast episode reflecting on several innovative but unsuccessful Nintendo-related products, including R.O.B., the Power Glove, and the Virtual Boy.

Seth Abramson has been assembling a master list of the Top 500 Indie NES Games, and the list includes the weird and wonderful Power Glove game 8-Bit Hero Trainer. Check it out at Retro.

The Shortcut has a rundown on the failure of the Humane AI Pin.

The popular YouTuber Marques Brownlee’s critique of the Humane AI Pin was titled “The Worst Product I've Ever Reviewed... For Now.” It racked up over 8 million views and is widely regarded as an Emperor Has No Clothes moment that sealed the fate of the wearable device. SatPost by Trung Phan wrote a meditation on the impact of this review entitled Roger Ebert, MKBHD and the Job of a Critic.

Interested in playing around with a Power Glove yourself? Ward and Austin note that there’s a great step-by-step guide to fiddling with the hardware on Instructables.

I took a media history class and ended up writing my final paper on the history of the power glove. It's one of those things that seems like it could have genuinely made groundbreaking technology if they hadn't cheaped out on mass production to get it into stores by Christmas.

Thanks for the article! I enjoyed learning about the various films and designs over the years that drew from the promise and disappointment.

Perhaps if the releases of these things had waited until all the kinks were taken care of, they might have actually been successful.