How newspaper comics created pop culture

A Q&A with Peter Maresca about the chaos and brilliance of 130-year-old Sunday funnies

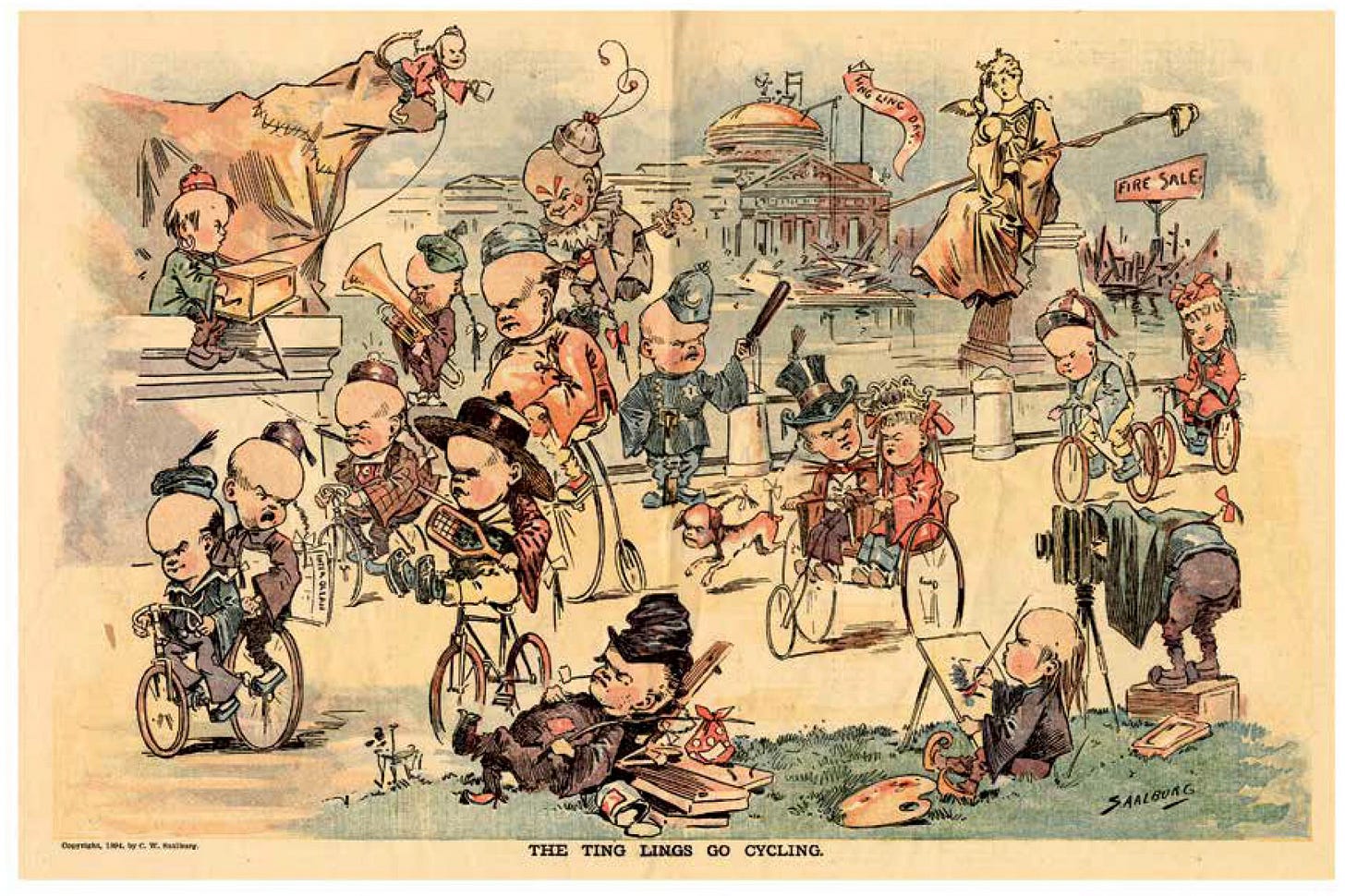

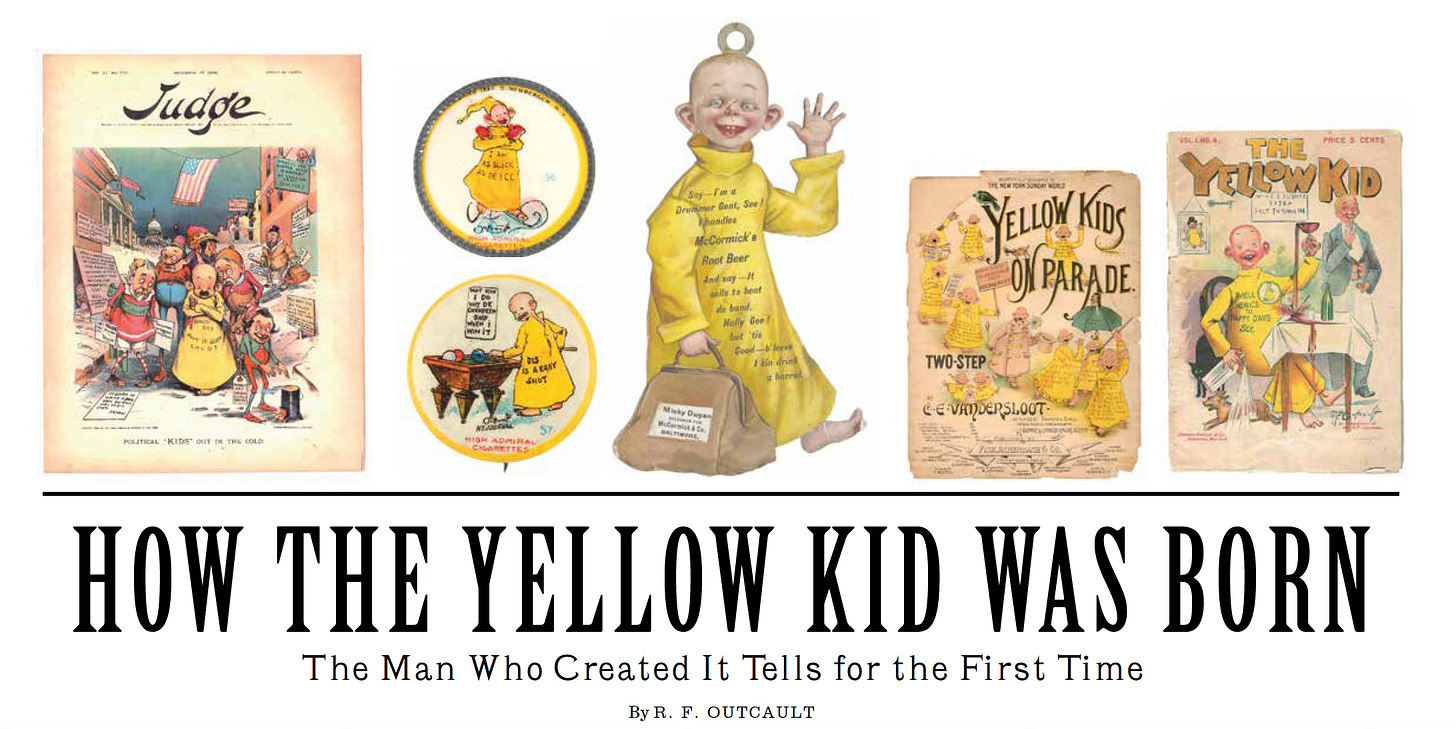

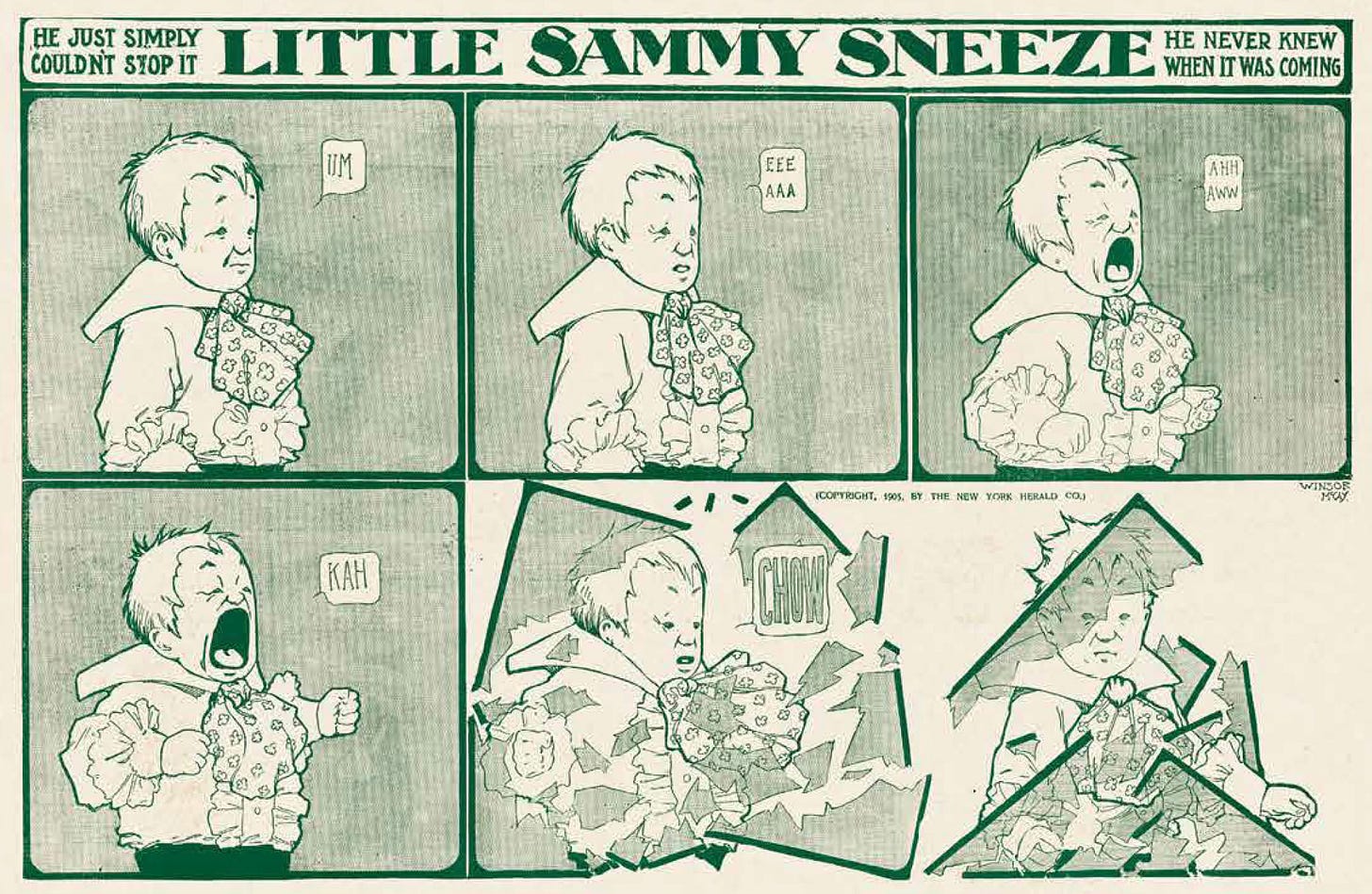

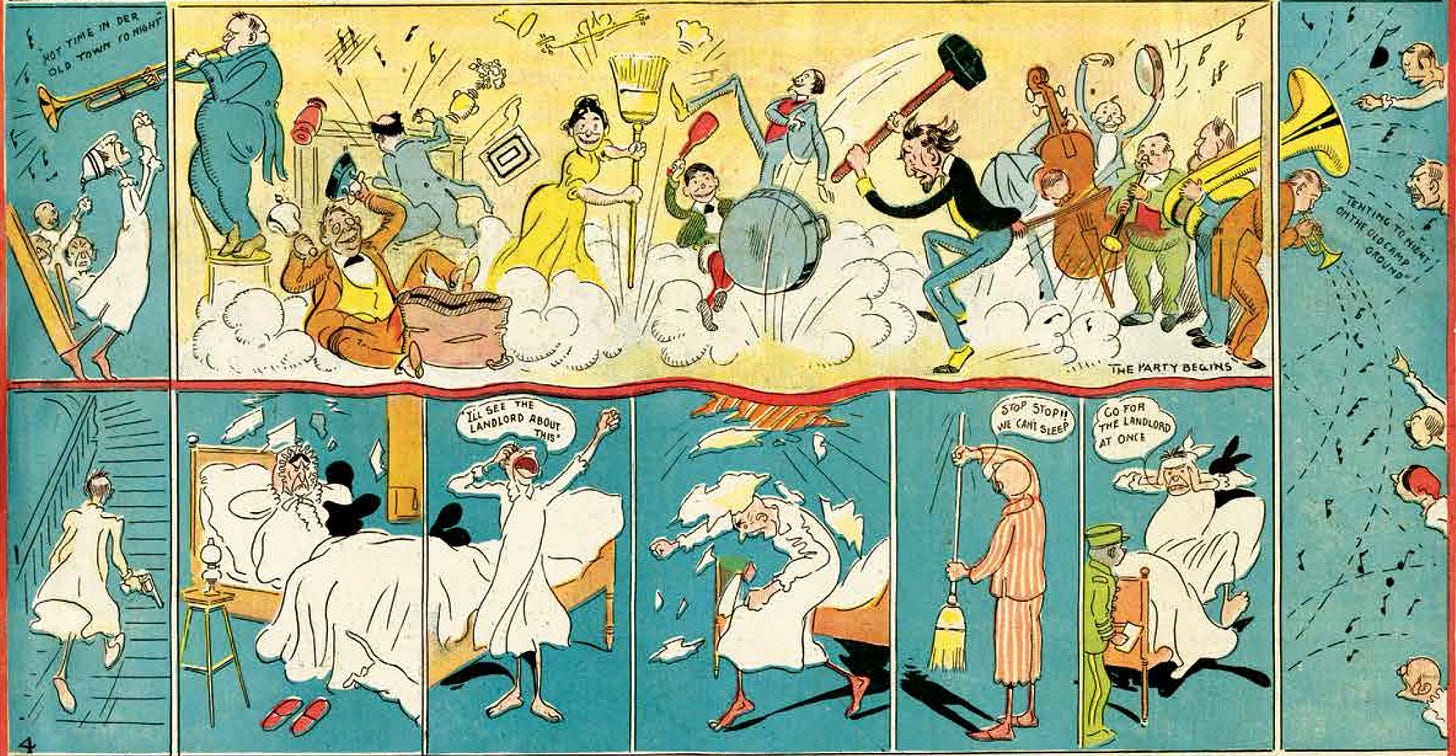

Before the First World War, back when cinema and recorded music were still in an embryonic state, newspaper comics were the most vibrant and widely seen art form in popular culture. Top artists like R. F. Outcault (The Yellow Kid and Buster Brown) and Winsor McCay (Little Nemo in Slumberland and Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend) were household names who commanded lavish salaries from publishing syndicates, which battled each other for exclusive contracts. The ravishing, colorful work of these artists filled page after page of full-color Sunday supplements of the era.

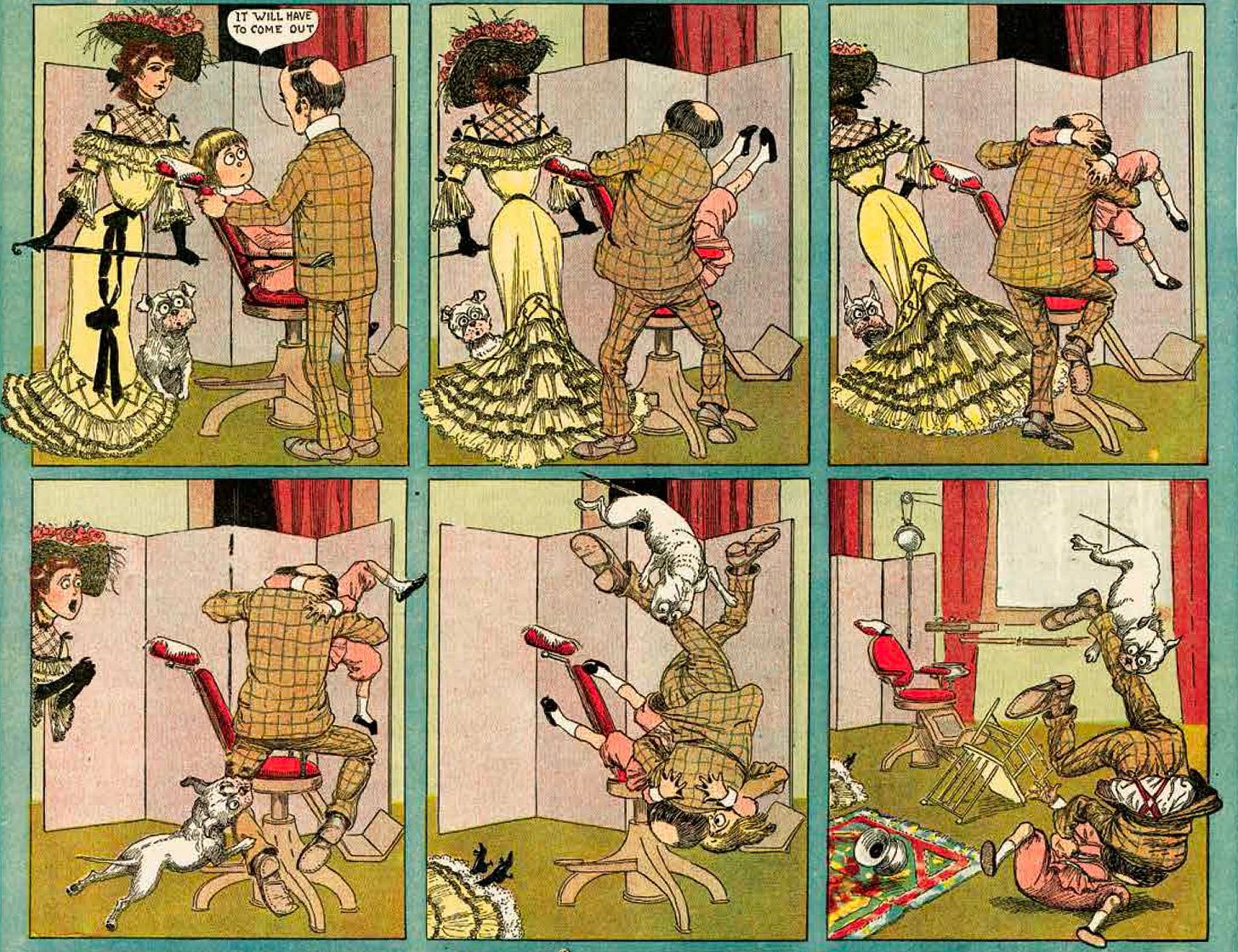

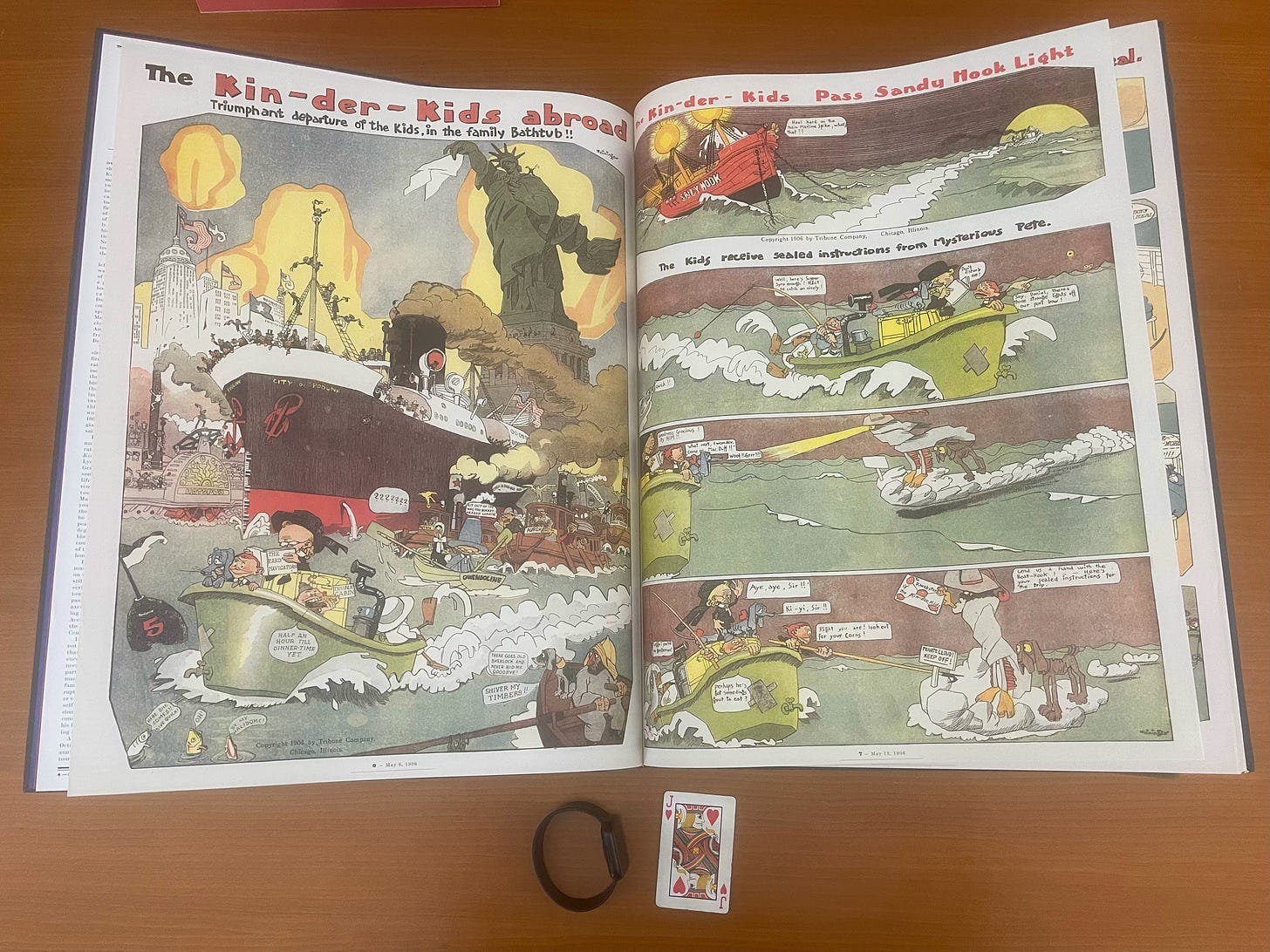

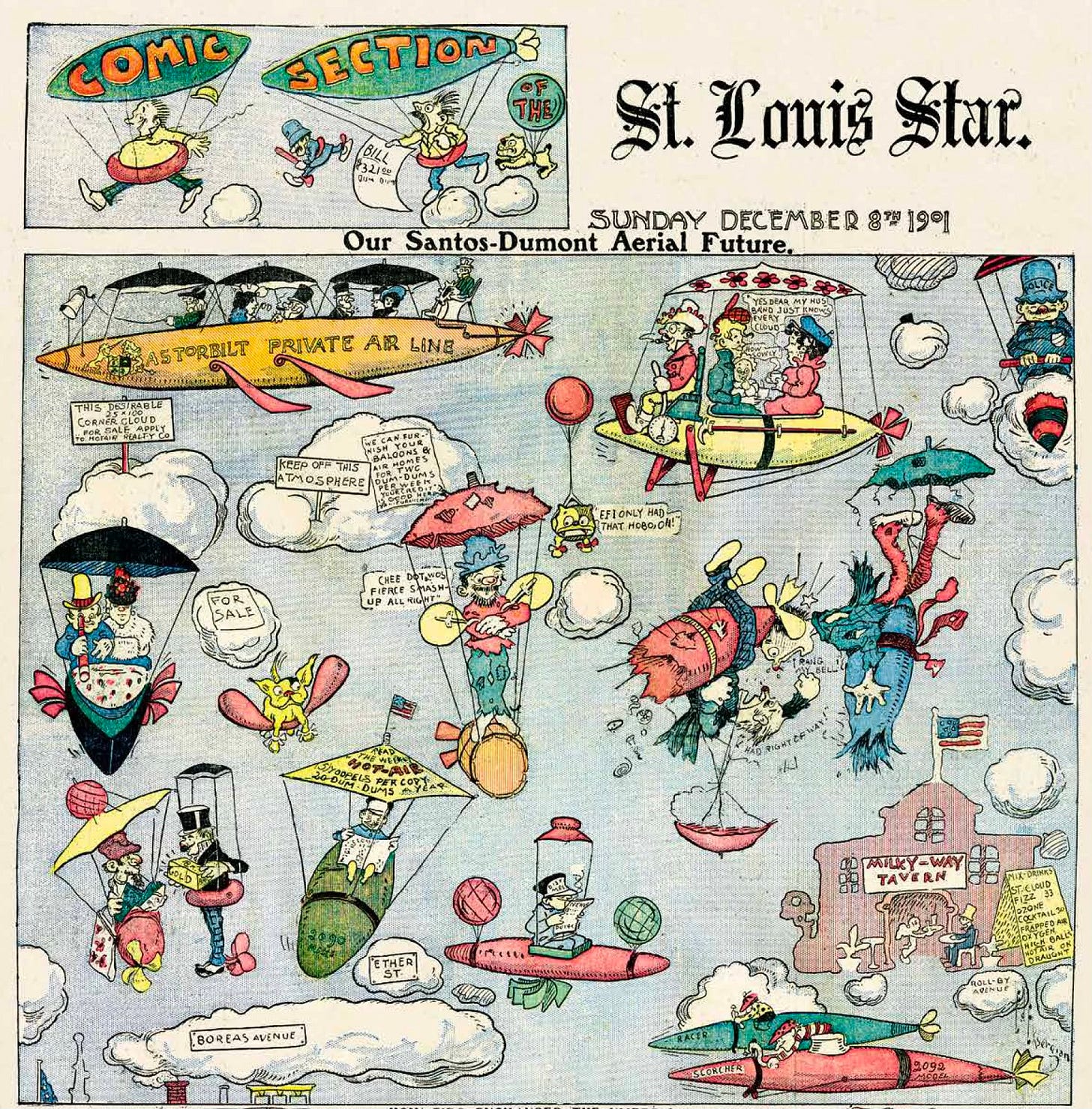

While cartoonists nowadays are often allotted just a quarter of a page for their Sunday funnies, artists back then were often given entire pages as their canvas. And the pages were enormous! Most newspapers nowadays use a 12 by 22 inch format, but back then, broadsheets could be 18 inches by two feet. Today, it’s hard to grasp how much spectacle could be crammed into those pages.

I know exactly how impressive these newspaper comics were in their heyday, and I know it because of Peter Maresca and his publishing company Sunday Press Books. Maresca took it upon himself to track down these comics, most of which have been unseen for over a century, digitally restore them to what they looked like when they were first published, and release them in compilations that match their original dimensions. Here’s a spread from Sunday Press Books’ Forgotten Fantasy: Sunday Comics 1900-1910 with my watch and a playing card underneath it for scale.

Sunday Press has published many award-winning collections of classic American newspaper strips, and re-established the reputations of several virtually forgotten illustrators. Many of its books have been in this enormous Sunday supplement format. The Palo Alto-based curator and publisher Maresca has done more than anyone to help modern audiences grasp the artistry and cultural impact of the form at the zenith of its popularity.

He believes that the most important work he has released is a companion piece to Forgotten Fantasy called Society Is Nix: Gleeful Anarchy at the Dawn of the American Comic Strip 1895-1915. It includes an amazing assortment of comics from that era, but it also gives an exhaustive history and pre-history of the newspaper comic, presenting fascinating archival material as well as essays from historians and prominent comics creators, both past and present.

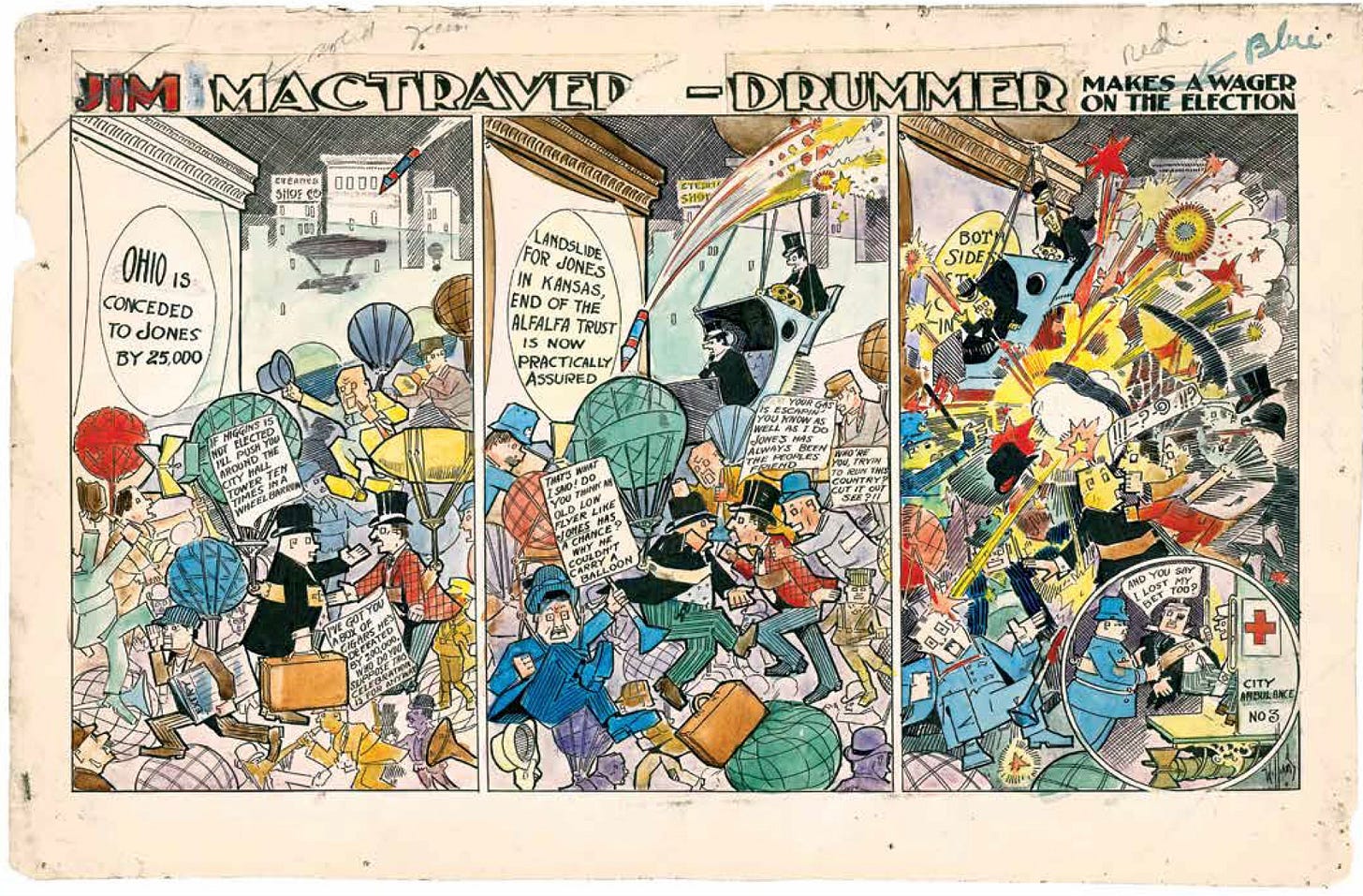

You might have heard of prominent strips like The Yellow Kid or Little Nemo, but Society is Nix highlights brilliant, idiosyncratic work from scores of lesser-known artists. The impression you get from reading the book is that there was a riot of creativity happening in newspapers from coast to coast, much of which was only seen by a small local audience. For example, the unique work below was only ever experienced by people in southwestern Ohio who happened to glance at the paper on a certain day in 1908.

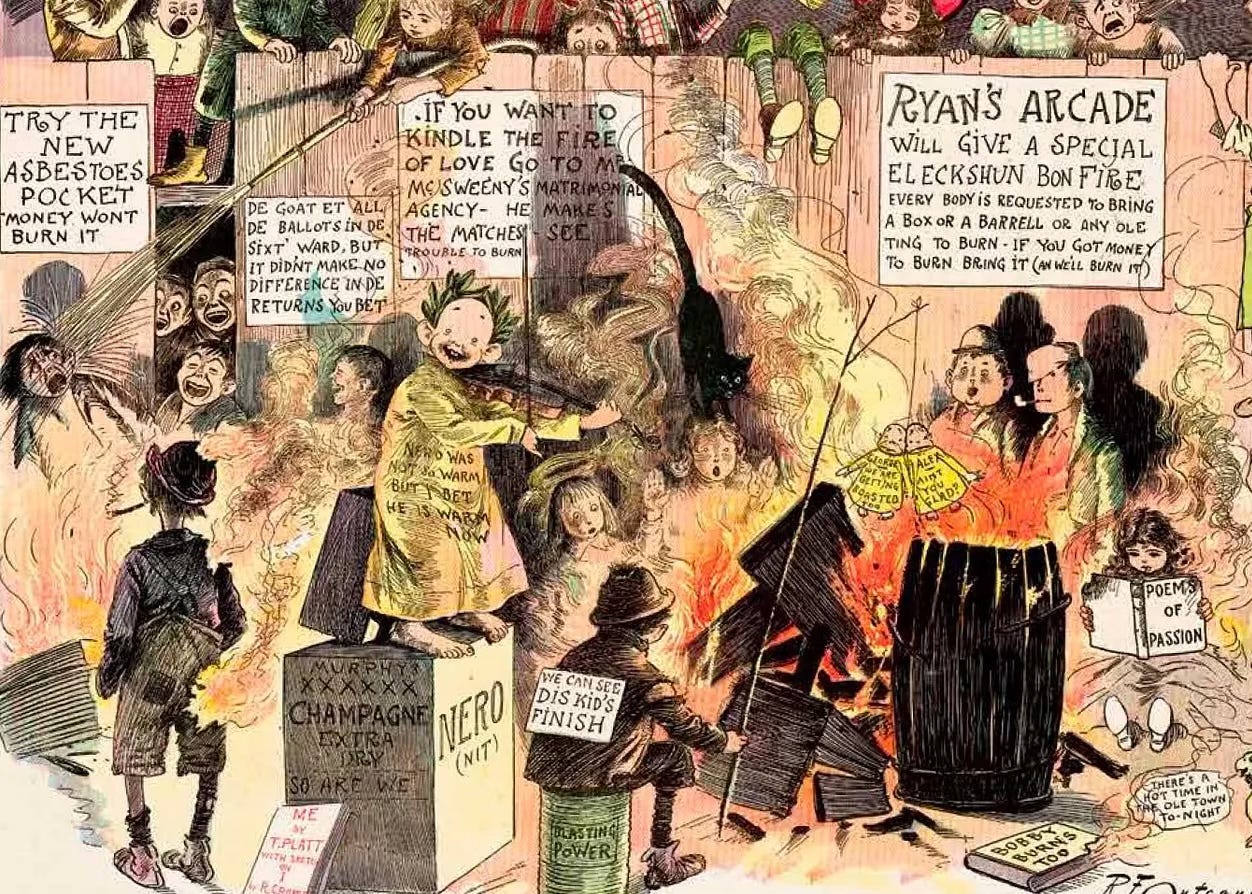

Society is Nix also stresses how subversive and rebellious this medium was in its infancy, and how the comics’ celebration of an unruly lower class and unassimilated immigrants flew in the face of stodgy American society of the era. (There are also thoughtful essays contextualizing the crude ethnic stereotypes and blatant racism that were commonplace in these comics.)

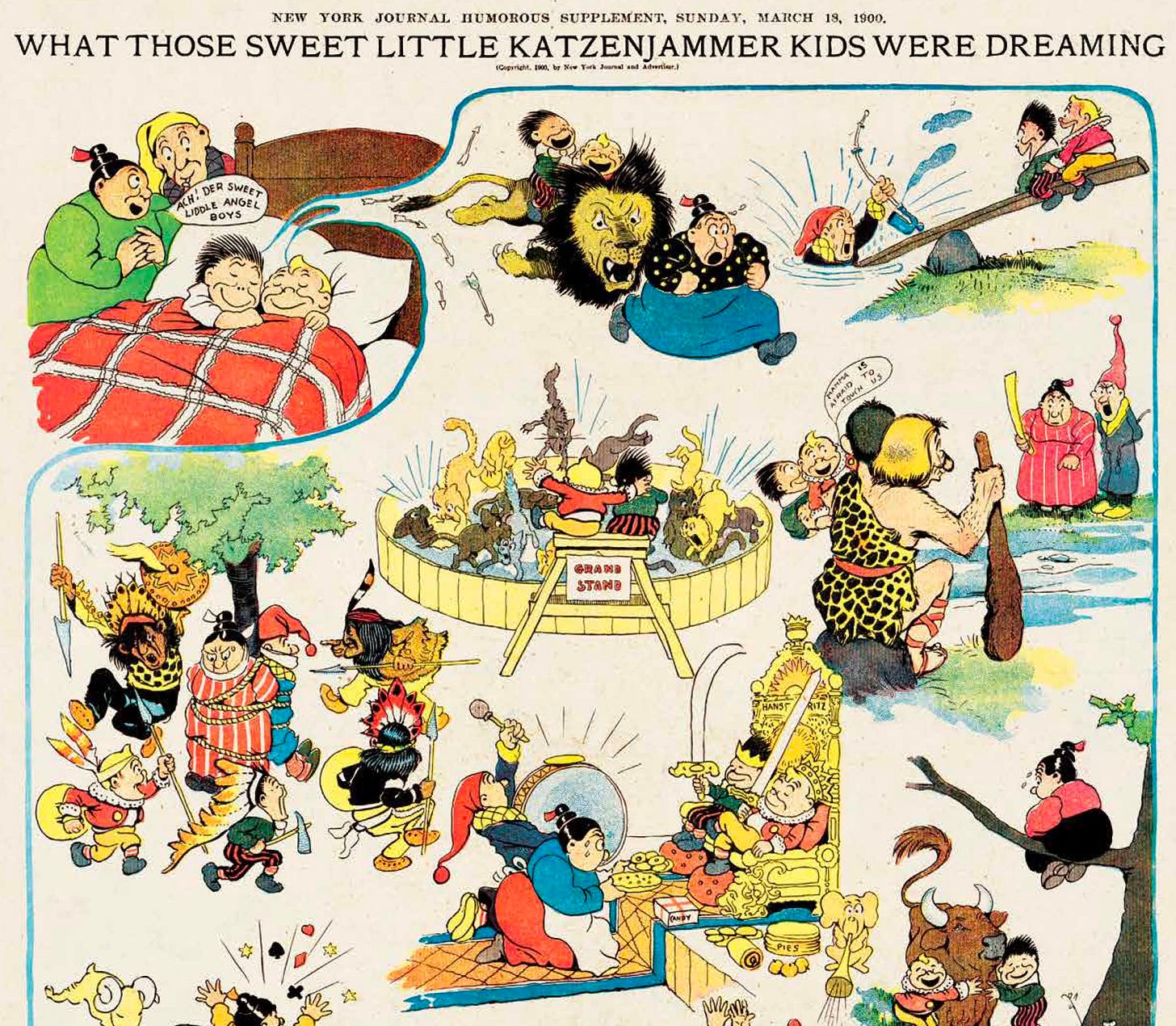

The name of the volume is taken from a line in The Katzenjammer Kids, an immensely popular comic about the exploits of two bratty German-American brothers who constantly wreak havoc. All dialogue in the strip is rendered in a dense “Denglish” dialect that mixed the characters’ old language with their new one. In one strip, a disapproving adult shouts, “Mit dose kids, SOCIETY IS NIX!”

Chris Ware called the original edition of Society Is Nix “a mind-blowing portable museum retrospective of the raw, tangled ferocity and frustration that went into the making of America.” Art Spiegelman declared that he “never thought anything like this could exist outside my dream life.” It was originally released in 2014, and used copies were recently on offer for $2499 on Amazon.

Thankfully, you don’t have to pay those ludicrous rates to resellers anymore. Maresca has partnered with Fantagraphics on a newly revised edition of Society Is Nix. It features new works from a wider array of artists, updated essays, and a handy index with minbios of every creator in the collection. I can’t stress enough that if you love comics and are at all interested in the history of the medium, you should click the link above and buy a copy.

I interviewed Maresca about the new edition of Society is Nix and the early history of comics. (All images in this post are from his fantastic book.)

PCP: First of all, congratulations on this new edition of the book! How do you describe Society is Nix to people who aren't familiar with it, and how does it fit into your broader project?

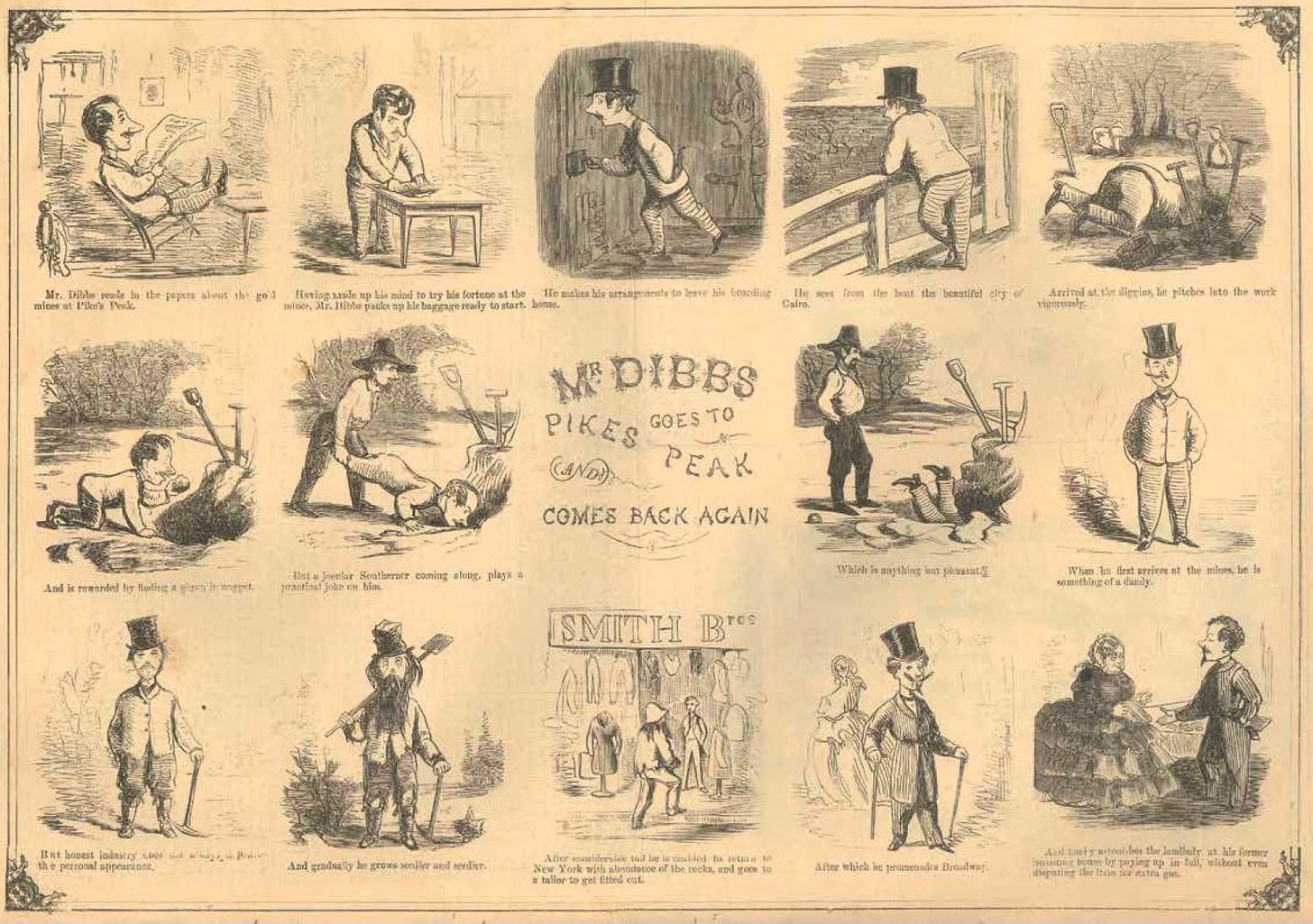

MARESCA: First of all, it gives the history not only of how American comic strips began, but also where they came from. It didn't just spontaneously generate—it’s not like the Yellow Kid comic appeared out of nowhere in 1895. There's a great deal of background information by several historians on the pre-history of comics—people who are the best in their field, like Thierry Smolderen, R.C. Harvey, and Richard Samuel West.

One big point I wanted to make is that when comics started, there were no rules. There were some humor magazines that had comics, and there were editorial comics in the newspapers, but there really was nothing like a comic strip section. So when publishers started to get artists to do these things, they were just given a blank 16-by-24 inch page, and they were able to just go wild.

The creativity was astounding. The artists could do whatever they wanted, and the comic strips themselves dealt with anarchic and anti-establishment topics. That's why I subtitled the book “Gleeful Anarchy at the Dawn of the American Comic Strip.”

There were a lot of actual anarchist movements going on in the world, particularly in Russia, that were parodied in the comics. And the streets of New York were crazy at the time. A lot of the book’s content is based on this anarchy and irreverence toward society.

Another element of the anarchy is the actual business. Newspapers weren’t really selling material to other newspapers at the time—everybody had their own thing. Then the giants of that time, Hearst and Pulitzer, began syndicating their comic strips to other newspapers who couldn't afford to make their own.

I wanted people to know the history, what it felt like to make and read these comics, and how modern comic artists were influenced by these men and women that I call “the founders of the funnies.”

PCP: Can you tell me in a nutshell the impact that the comics had on the different newspaper syndicates and their battle for audience share?

MARESCA: The first color comics section came out in Chicago. There was a publisher named Kohlsaat who was vacationing in Paris, and he discovered a magazine, Le Petit Journal, that had a very inexpensive color process. In the States, color lithography was very expensive, and certainly wouldn't be thrown away on a mere newspaper. Kohlsaat brought this printing process back to Chicago and used it in his Chicago Inter-Ocean for fashion coverage and political cartoons and things.

Joseph Pulitzer saw this and said, hey, I can bring my little editorial cartoons to life with color and really explode this business. He understood that a lot of his audience in New York City were immigrants who did not have a strong command of the English language, so they couldn't read the newspapers. But these color images were so striking, and they could tell stories with very few words or no words at all.

The irreverence of the comics gave these immigrants a chance to poke fun at the people who were controlling their lives, whether it was landlords or cops or teachers. Pulitzer realized that this was the way to sell newspapers. And it was just incredible how his circulation exploded.

William Randolph Hearst came along in the late 1890s. He saw what was going on with comics, and it was just like the movie Citizen Kane. The Kane character was Hearst, and there’s a scene in the movie where Kane is looking at a photograph of the staff of the newspaper across the street that had huge circulation, and then the film cuts to that same staff sitting in Kane’s office getting their photograph taken—they were all working for him now. What Kane did in the movie, Hearst did with comics. He poached all the best writers and artists that had been working for Pulitzer.

There was a huge circulation war going on at the time between Hearst and Pulitzer. And at the center of that battle, believe it or not, was The Yellow Kid. Hearst had stolen away the artist RIchard F. Outcault from Pulitzer to do The Yellow Kid for his paper. Pulitzer still had the trademark for the title “The Yellow Kid,” so he got one of his artists to do a version of the Yellow Kid too. So there were two artists at the same time doing what was essentially the same character for different newspaper barons.

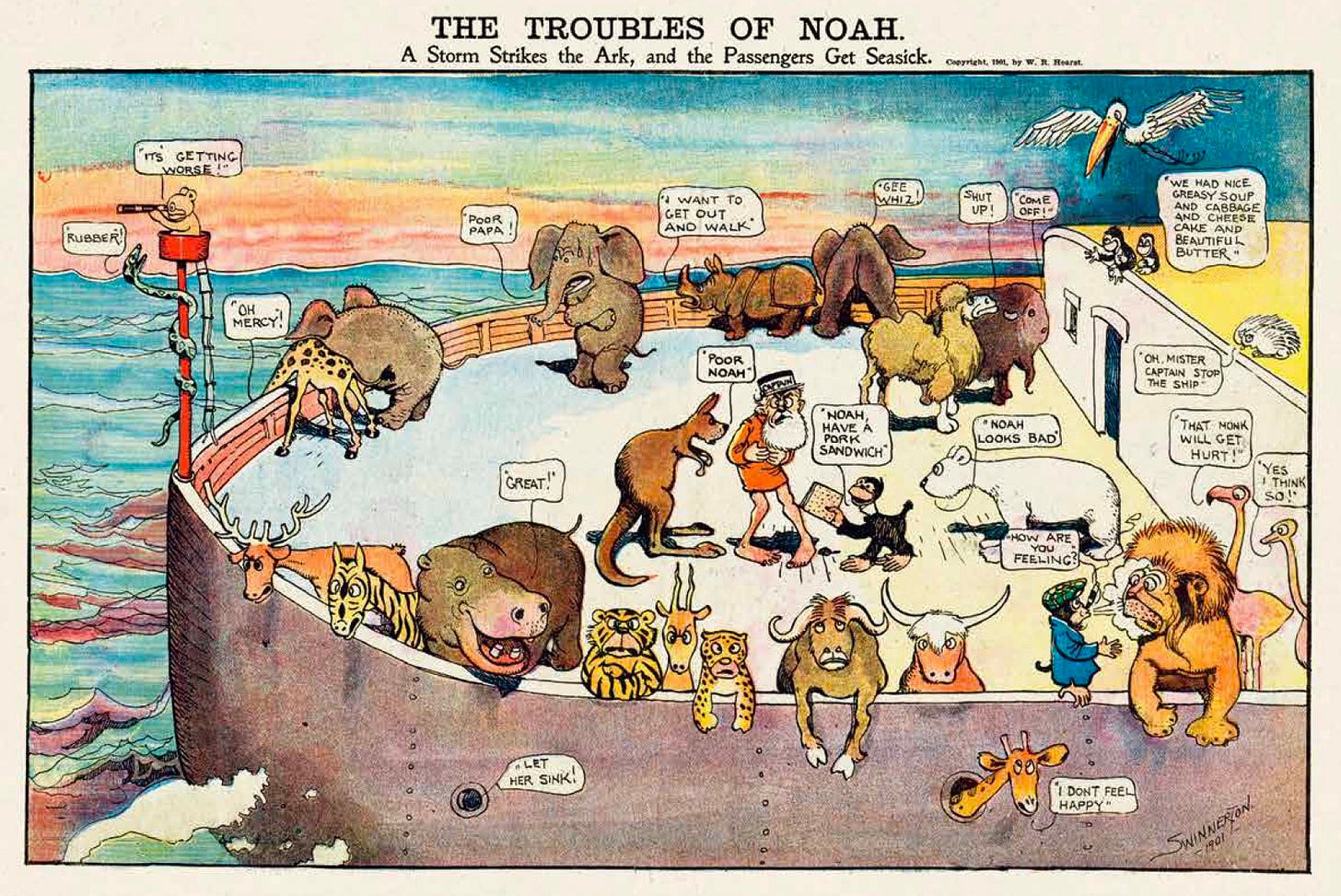

Yellow journalism was the term they coined for the war between these newspapers, and it was named after this kid in a yellow nightgown from the comics. Hearst ended up winning the war, and I think one of the reasons is that he caught on that people wanted regular characters. The Pulitzer papers were a lot of one-shots—great artists doing their thing, but with different subject matter each week. Hearst had plenty of one-shots, but he had his artists concentrate on characters like the Katzenjammer Kids, Opper's Happy Hooligan, and Swinnerton’s Little Jimmy. His newspapers really took off because people wanted to see what these characters were doing each week.

PCP: One of the things that shocked me was how much chaos and violence there were in these early comics. We think of this period as being very straitlaced, and we think of the funnies as being kid-friendly and mild, but they absolutely weren’t in the 1890s and 1900s. It reminded me of how pre-1935 films were far more risqué and dealt with darker topics than the ones made after the Hays Code was established during the Depression.

MARESCA: Yes, once the newspapers became more established, they started getting complaints, just like movie theaters started getting complaints from people who saw all this disrespect and the anarchy and didn't like it. And just like the Hays Commission came about in the 1930s for movies, the newspaper syndicate owners and the publishers were getting a lot of criticism as well, and that's one of the things we talk about in the book.

PCP: There were a lot of hand wringers and arbiters of culture 120 years ago insisting these things in pop culture were warping kids' minds and decaying their morals, just like they always do. And the outcry was probably exacerbated by the fact that, as you point out, this was arguably the first example of pop culture as we currently understand it. I think your term is “temporally shared experience.”

MARESCA: The newspaper comics really were the first form of popular culture as we now know it. Dickens was popular culture; Shakespeare was popular culture; street music and dime novels were popular culture. But those were all asynchronous—small numbers of people were viewing them at any given time.

Newspaper comics were the first time that people all over the country were taking in the same entertainment at the same time. Someone in Los Angeles could be talking around the water cooler about the latest Katzenjammer Kids strip, and it would simultaneously be the the same topic of conversation in New York City or Chicago or St. Louis or anywhere else. This was way before radio and motion pictures. It's absolutely a first for pop culture.

PCP: Was there a sense that a fine illustrator was slumming if they went to the comics at the time? Or were they paid so handsomely that it wasn't a factor?

MARESCA: A lot of them were very well paid, but part of that was merchandising. When Outcault started Buster Brown, he owned the character, and he made millions just selling merchandise for his characters.

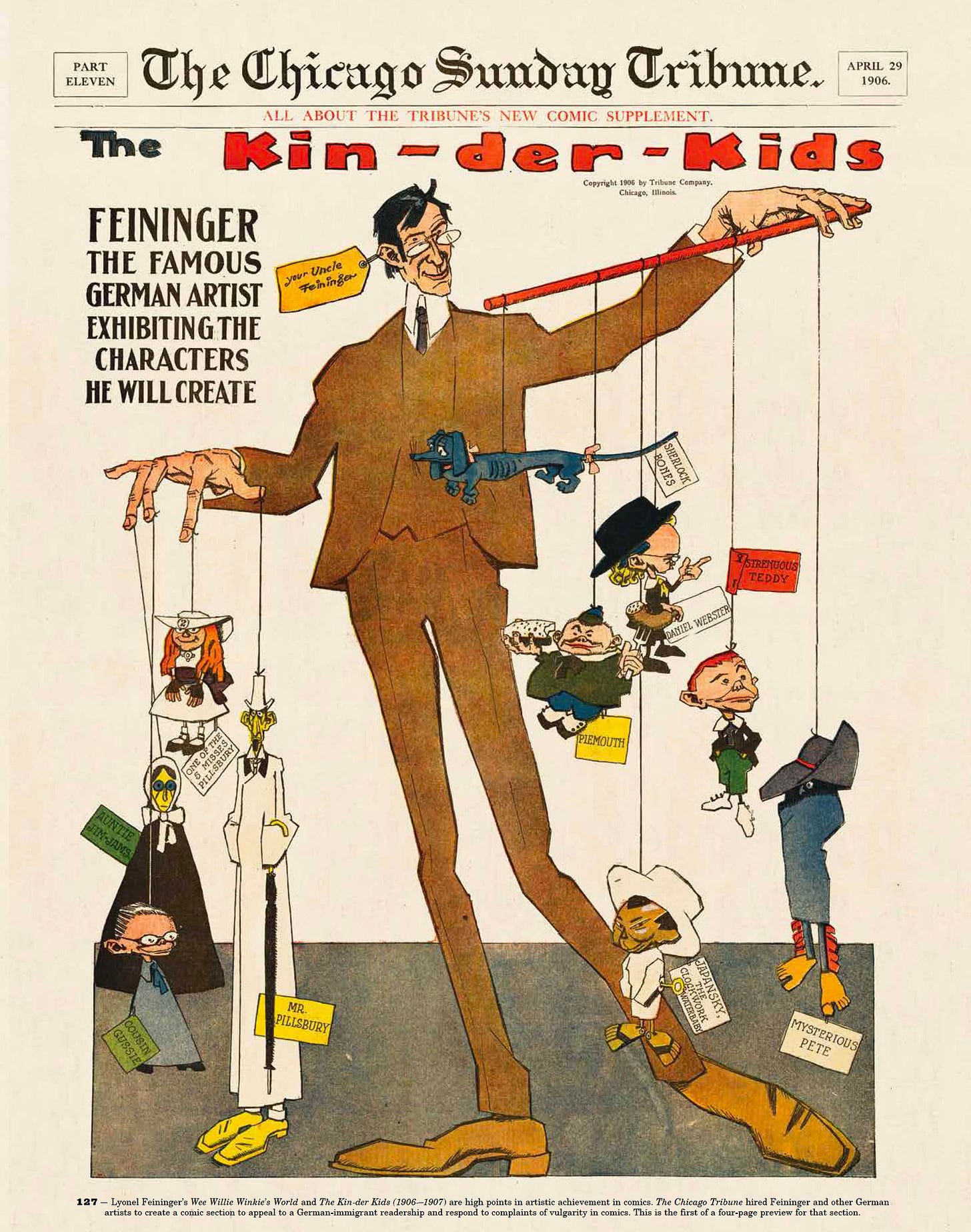

You mentioned fine artists. There was a time when The Chicago Tribune tried to bring in great artists to create a line of more “refined” comics. They went to illustrators for German magazines, because there was a huge German immigrant population in Chicago at the time. They lined up Lyonel Feininger and a couple of other German artists.

They did a complete comic section of German artists drawing family-friendly comics; and it failed miserably. That isn't what kids wanted, or what the immigrant community wanted. They wanted anarchy. They wanted disrespect. They wanted chaos. It only lasted about a year and a half. Then The Chicago Tribune picked up Buster Brown and a version of the Katzenjammer Kids and so forth. They went in the same direction as other syndicates and other newspapers.

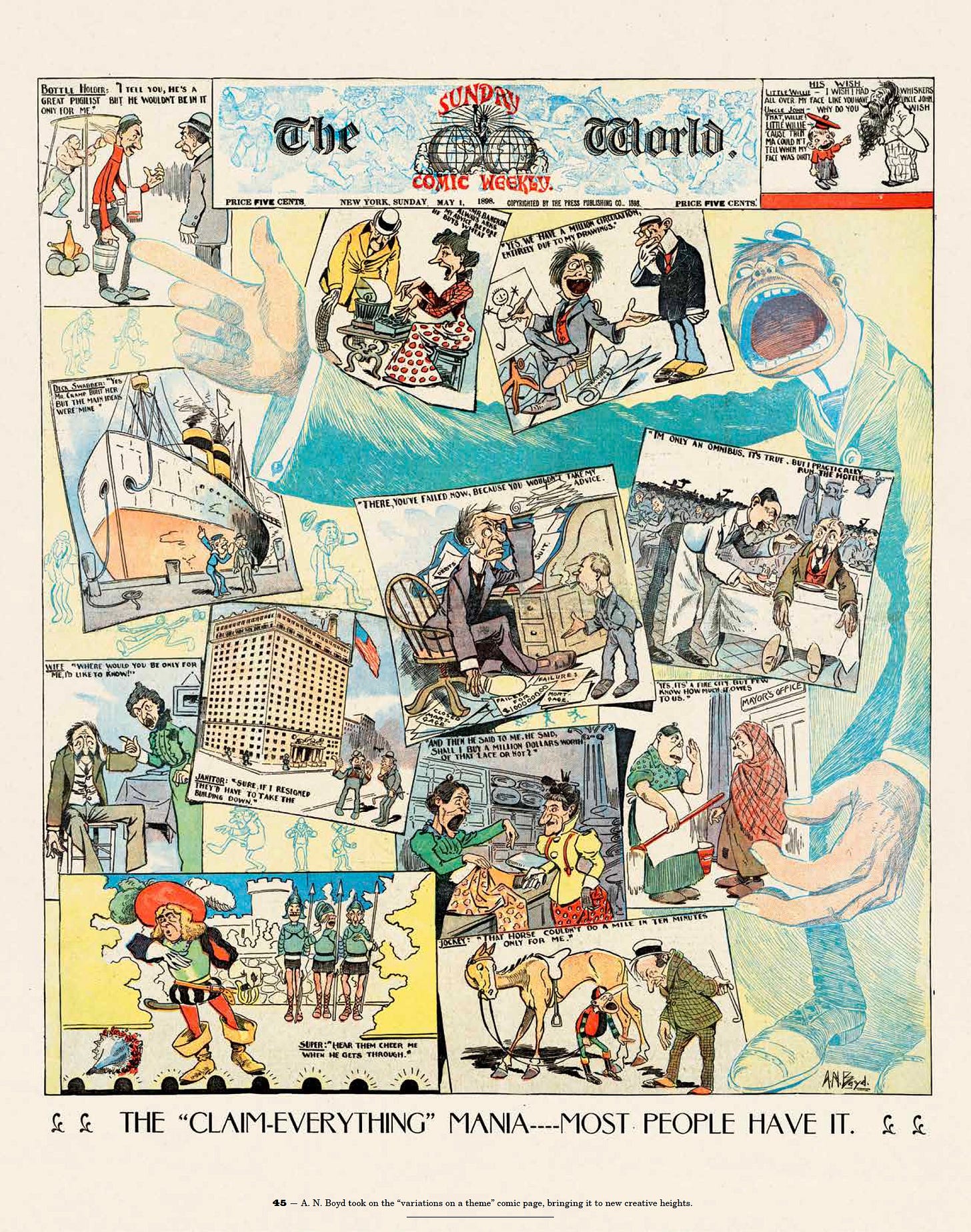

PCP: We think that comics just recently discovered the idea of characters breaking out of the set square boxy panels, or breaking the fourth wall and talking directly to the readers. But it’s actually as old as the medium, right?

MARESCA Sure, sure. So much of the stuff that we think was invented when we were kids had actually been done long before.

There's a two-spread edition in Pultizer’s New York World in 1897 that's done by seven different artists, about how they each look at summertime. And the pages are separated into one, two, three, like seven different triangles. And each one of these different artists tells their story within that triangle, using one panel or six panels or however they want to do it. Just an incredible layout.

All these artists would get together and do their own bit. I always thought this sort of comics jam was invented with the underground comix. But it was done as early as the 1890s. Sometimes the artists would just work together on a large page with different little vignettes. And sometimes they'd actually create a 12 or 16 panel story with all of their different characters interacting with each other.

One of the reasons this was common then is, like with the underground comix, they were working in close proximity. These people making newspaper comics would go to work in the studios. And they'd be sitting there in their jackets and ties at their desks and drawing their comics next to each other. So it was very simple to take a page they were working on and pass it around and have other artists work on it.

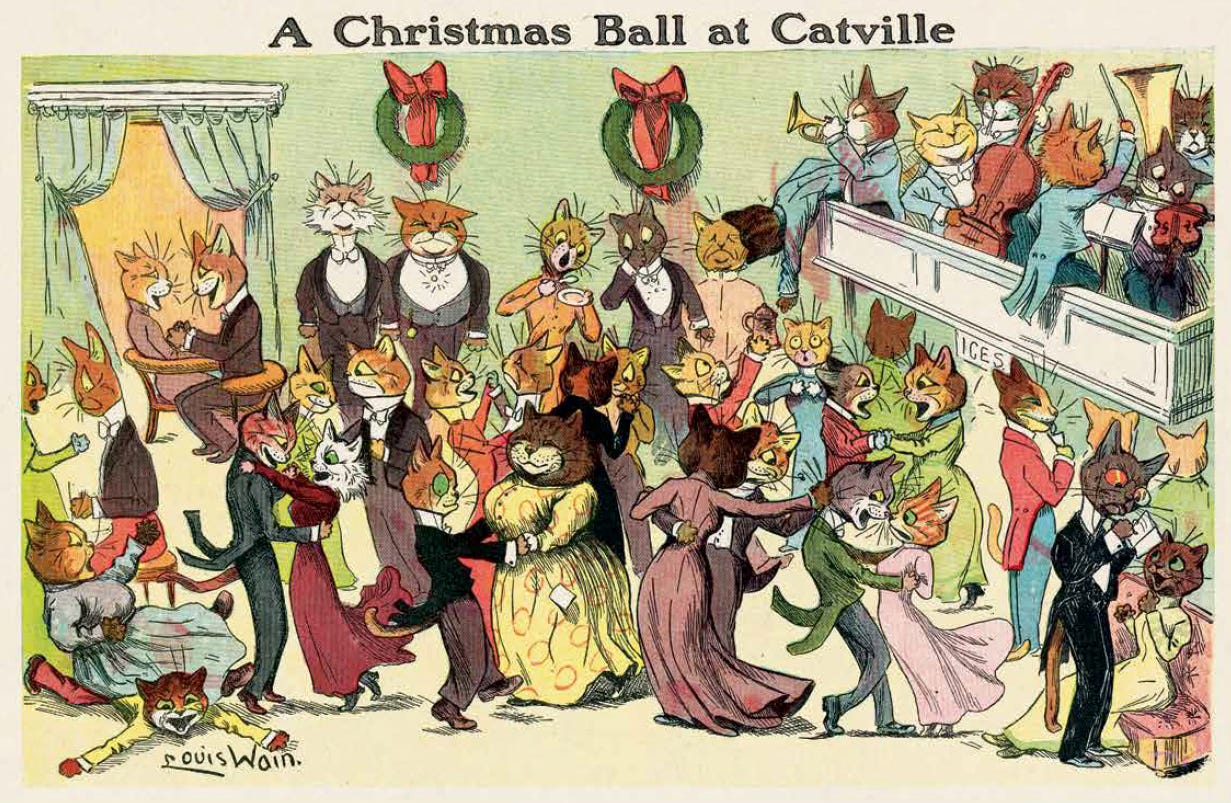

PCP: I'd love to hear about some of the iconic artists that have been added to this new edition of Society is Nix. You've added a comic from Louis Wain, the father of all cat memes. He later developed severe mental health issues, and his artwork got increasingly kaleidoscopic and psychedelic.

MARESCA: Yeah, his story is fascinating. There's a recent movie about him as well, with Benedict Cumberbatch.

As I went through the original book, I noted some people that were missing, and realized that I had the opportunity to include things that I'd come across since it was published. I didn't have anything from Rea Irvin, the original art director for The New Yorker who created the magazine’s mascot Eustace Tilly. He had a couple of successful comic strips in the early days, and I wanted to make sure I included him.

There were a couple other people who I added, or who had their presence expanded. I put in another one of Kate Carew’s strips, and added one by Grace Drayton. In total, there's about twenty-five comic strips that were added.

PCP: What's next for you and Sunday Press?

Maresca: I would like to do another edition of Forgotten Fantasy and do the same thing I did with Society is Nix—put more comics into it and give it a wider distribution than the original one, because that's also out of print now. I’d also like to do a book on George McManus. There are lots of things he did that people aren't aware of.

![DATELINE: ST LOUIS POST DISPATCH APRIL 16 1904 | TITLE: THE NEWLYWEDS- THEIR FIRST EVENING AT HOME. | PANEL 1 [couple in the drawing room embracing] HUSBAND: LEAVE ME, PRECIOUS PET? NEVER! I’LL GO AND HELP YOU. WIFE: NOW DEAREST LOVE I MUST LEAVE YOU AND GET THE SUPPER.PARROT: WOULDN’T THEY MAKE YOU WISH YOU’D NEVER LEARNED TO TALK? | PANEL 2: [couple in kitchen, husband wears apron and peels potatoes] WIFE: WHERE DID YOU LEARN TO PARE POTATOES SO LOVELY, DARLING. HUSBAND: BE CAREFUL OF THESE DEAR LITTLE HANDS, TOOTSIE WOOTSIE. PARROT: THEY’VE GOT ROMEO AND JULIET TIED TO THE POST. | PANEL 3: [couple in kitchen, husband has dropped knife and dances in agony] WIFE: OH DEAREST YOU’VE CUT YOURSELF WITH THAT CRUEL KNIFE! HUSBAND: ONLY A SCRATCH LOVEY, AND I GOT WORKING IT FOR YOU. PARROT: STOP THE SHIP! I’M SEASICK. | PANEL 4: [couple in kitchen, wife is tending to husband’s wound, neither of them notice the pan on the stove has burst into flames] HUSBAND: DO YOU REMEMBER WIFIE DEAR, THE FIRST TIME WE MET? WIFE: AND IS MY OWNEST OWN BETTER NOW? PARROT: FIRE -FIRE! FLOOD! POLICE! LUNATICS! | PANEL 5 [couple in kitchen, a bunch of burly firemen burst in and dous them with a high pressure hose] PARROT: NOW YOU’VE GOT HIM! DROWN HIM! | PANEL 6: [the couple are soaked to the bone. They embrace as the firemen leave looking disgusted]] HUSBAND: I’D GO THROUGH FIRE AND WATER FOR YOU FOREVER DEAR. WIFE: MY HERO! PARROT: YOU DION'T PLAY THE HOSE ON EM LONG ENOUGH DATELINE: ST LOUIS POST DISPATCH APRIL 16 1904 | TITLE: THE NEWLYWEDS- THEIR FIRST EVENING AT HOME. | PANEL 1 [couple in the drawing room embracing] HUSBAND: LEAVE ME, PRECIOUS PET? NEVER! I’LL GO AND HELP YOU. WIFE: NOW DEAREST LOVE I MUST LEAVE YOU AND GET THE SUPPER.PARROT: WOULDN’T THEY MAKE YOU WISH YOU’D NEVER LEARNED TO TALK? | PANEL 2: [couple in kitchen, husband wears apron and peels potatoes] WIFE: WHERE DID YOU LEARN TO PARE POTATOES SO LOVELY, DARLING. HUSBAND: BE CAREFUL OF THESE DEAR LITTLE HANDS, TOOTSIE WOOTSIE. PARROT: THEY’VE GOT ROMEO AND JULIET TIED TO THE POST. | PANEL 3: [couple in kitchen, husband has dropped knife and dances in agony] WIFE: OH DEAREST YOU’VE CUT YOURSELF WITH THAT CRUEL KNIFE! HUSBAND: ONLY A SCRATCH LOVEY, AND I GOT WORKING IT FOR YOU. PARROT: STOP THE SHIP! I’M SEASICK. | PANEL 4: [couple in kitchen, wife is tending to husband’s wound, neither of them notice the pan on the stove has burst into flames] HUSBAND: DO YOU REMEMBER WIFIE DEAR, THE FIRST TIME WE MET? WIFE: AND IS MY OWNEST OWN BETTER NOW? PARROT: FIRE -FIRE! FLOOD! POLICE! LUNATICS! | PANEL 5 [couple in kitchen, a bunch of burly firemen burst in and dous them with a high pressure hose] PARROT: NOW YOU’VE GOT HIM! DROWN HIM! | PANEL 6: [the couple are soaked to the bone. They embrace as the firemen leave looking disgusted]] HUSBAND: I’D GO THROUGH FIRE AND WATER FOR YOU FOREVER DEAR. WIFE: MY HERO! PARROT: YOU DION'T PLAY THE HOSE ON EM LONG ENOUGH](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!wV6y!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb39d7a82-4771-4c7d-b7bd-1c23484bb6de_1786x988.heic)

The other thing I want to do is take a look at how the comics changed from 1915 to 1929. There was huge growth of the middle class, people became more educated. Society changed, and the comics started telling new kinds of stories. Instead of mobs of kids in alleyways, comics increasingly focused on family life.

PCP: Are you still discovering new stuff? New old stuff?

Oh yeah. Once a year, I'll go to Ohio State University and look through their archives at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. That was where the collector Bill Blackbeard's collection went—millions of comics clippings, truckloads of stuff that they're still sorting through. Whenever I go there, I see things that I’ve never seen before.

Thanks for reading! Go buy Society Is Nix: Gleeful Anarchy at the Dawn of the American Comic Strip 1895-1915 Revised Edition.

ELSEWHERE:

(Steven Smith) highlights several other books curated and edited by Maresca, including Thimble Theatre & the Pre-Popeye Comics of E.C. Segar: Revised and Expandedand The Nancy Show: A Celebration of the Art of Ernie Bushmiller. Read the post here.

The weekly lecture series New York Comics & Picture-story Symposium (postings by the great artist Ben Katchor) recently hosted Maresca and the co-creators of the collection Jimmy! The Comic Art of James Swinnerton. Read background on the event here and watch the full video of the event here.

Peter Maresca (@petercollects) is on Substack.

GREAT article and interview! Really interesting topic; thanks for adding all the images, too.

I think back to all the time we spent in that awful RTF301 class learning about yellow journalism, and not once did they tell us anything interesting about the war between the Yellow Kids. Crimez.