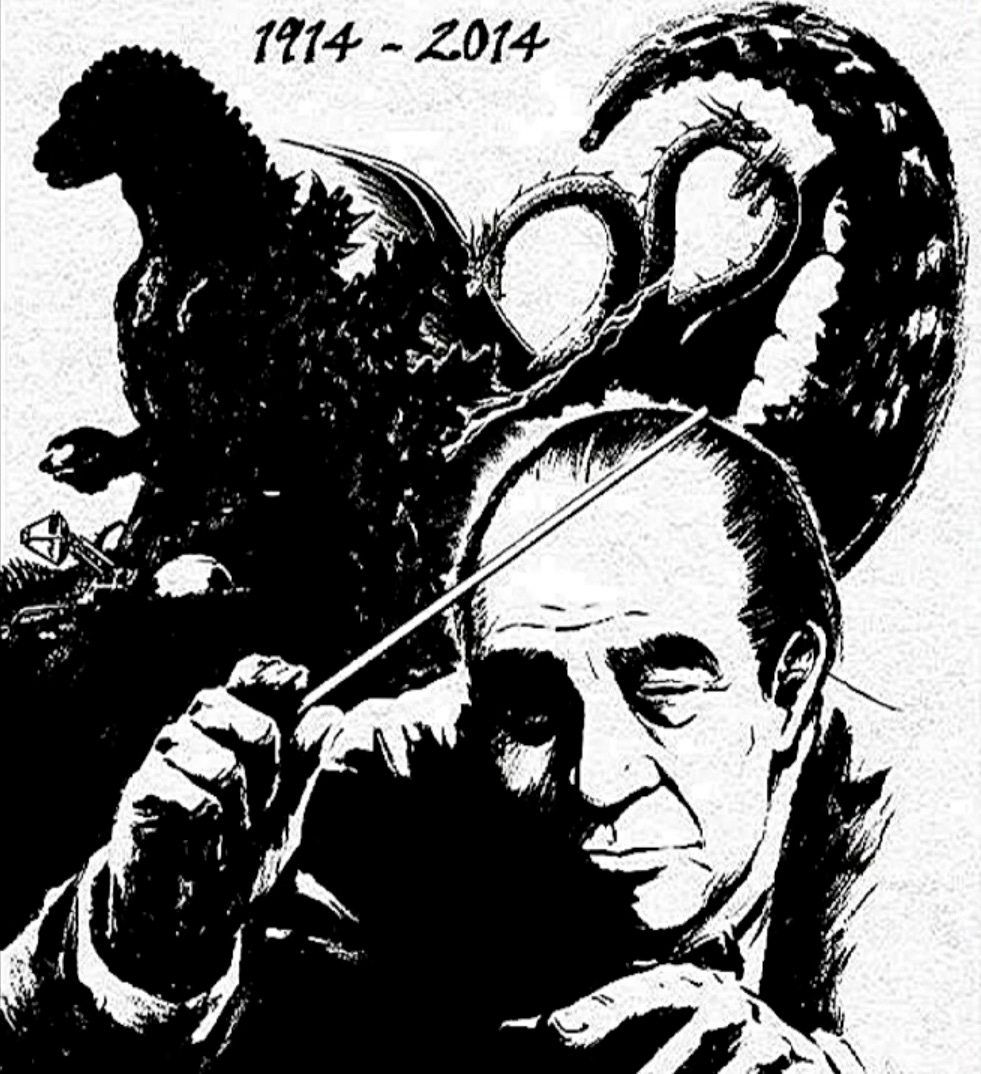

The Classical Composer Who Created Godzilla's Roar

Exactly 70 years ago, Akira Ifukube crafted the most memorable sound effect in cinema history

The original 1954 film Godzilla, released 70 years ago this month, left some pretty big footprints. The appearance of the giant lizard is iconic, though it can now seem dated—a man in a rubber lizard suit is more likely to provoke snickers than gasps of terror. But the creature’s roar maintains all of its primal power—it’s an earth-shattering, earsplitting shriek of fury and pain.

The memorable sound was created by composer Akira Ifukube, who also crafted the film’s iconic score. “It’s the most important sound effect in cinema history,” Erik Aadahl told me. He was one of the supervising sound editors on the 2014 Godzilla Hollywood reboot. (Bits of this post previously appeared in an article for WIRED.)

The unsung heroes of cinema are the people who craft the audio—watch a rough cut with no score or sound f/x added, and even a great film looks plodding and dull. Ifukube is one of the most illustrious and talented composers in the history of cinema. He’s known for his classical compositions, and he worked extensively on dramatic films by great directors like Akira Kurosawa and Josef von Sternberg as well as Kon Ichikawa (The Burmese Harp, Fires on the Plain), Hiroshi Inagaki (The Samurai Trilogy), Kenji Misumi (creator of the Zatoichi and Lone Wolf and Cub series).

But Ifukube is most famous for his dozens of collaborations with kaiju (giant monster) auteur Ishiro Honda, beginning with the original Godzilla that birthed the entire genre.

Ifukube never thought that the lowbrow giant monster movie was beneath him. “My specialty was biology,“ he said. “I couldn’t sit still when I heard that in this movie the main character was a reptile that would be rampaging through the city.” (All quotes here from the original filmmakers of the 1954 Godzilla are cadged from the invaluable tome Japan's Favorite Mon-Star : The Unauthorized Biography of "The Big G.")

The composer only had access to the raw footage of the rough cut sans special effects, and had to build his musical score for the film out of whatever he could glean from the script and a small model of Godzilla. He said that the special effects guru Eiji Tsuburaya was protective of footage of the monster itself before the film was completed, and told him, “If you look at the expressions on the extra’s faces you’ll know how scary the thing is behind the mountain.”

Ifukube crafted a bass-heavy musical arrangement heavy on strings and brass to capture the thudding rampage of the monster. He later conducted the NHK Orchestra as it performed over the finalized footage. The score was recorded while the foley artist simultaneously created the mechanical foley effects of Tokyo being destroyed—the archaic audio setup only had four tracks for all of the different sound components in the film, so these elements had to be created together, live and on the fly.

The following clip from the film hits different when you watch it knowing that the slightest mistake by any musician or sound technician meant that the whole scene would have to be re-performed.

But the timeless shriek of the monster was devised and recorded beforehand. The director Honda dictated that Godzilla should roar even though no reptile actually does that. (The closest thing in nature are the bellows and growls that crocs and alligators produce during mating season.) The film had a sound recordist and a sound effects designer, but Ifukube was so deeply involved in the project that he wanted to craft the monster’s roar himself.

The sound recordist Hisashi Shimonaga experimented with the actual sounds produced by predatory big cats and raptors played back at different speeds, but that was found wanting. Ifukube borrowed a double bass from Japan Art University and loosened the strings to make the low-pitched instrument even more resonant and bass-y. He rubbed a leather glove covered with pine tar resin up and down the strings to create an eerie bellowing sound. The recording of that was then slowed down to make it even more plaintive and menacing. This is the final result.

Aadahl diagrams the elements of that sound that he strove to recreate for the 2014 film. "The main element of the roar is this metallic shriek, accompanied by an earth-shattering sound,” he says. “But there is another component that is kind of a bellowing finish. There’s the 'RRAAAAAAAAH' of the attack and then an 'OWWWOOO-WOOMPH' of the finish."

Godzilla’s roar is a sound effect, but it’s also a vocal performance. “As sound editors, we’re trying to illuminate the soul of this creature,” says Aadahl. “There’s a quality of enormity and triumph to it. On the other end, there’s a pathos. There’s an arc to that character that I find to be pretty profound.”

The Godzilla series moved in a more tongue-in-cheek direction as the kaiju cycle progressed; an understandable shift given the stiff monster costumes and the unconvincing miniature cityscapes. But the original 1954 film was meant to be harrowing and tragic, the product of a society that had recently endured the firebombing of scores of cities and two atomic bombs—a level of cataclysm and devastation that had previously been unimaginable.

Modern audiences might snicker at the dated effects work, but close your eyes and listen to the monster’s furious, anguished shriek, and the artistic intent of the film is unmistakable.

ELSEWHERE: Gianni Simone’s Tokyo Calling newsletter has an interesting post about what was happening in Japanese society at the time of the film’s release in 1954—check that out here. Matt Alt’s Pure Invention newsletter has a fascinating critique of the most recent Godzilla film, which is set in the aftermath of WWII and has the somber tone of the original film. You can read that here.