The Father of all Pop Culture Zombies

This travel writer introduced the undead to America. He also ATE HUMAN FLESH.

“Zombie movies have a lovely transparency,” Danny Boyle told Dazed Digital on the press tour for his recent film 28 Years Later. “Concerns you have about racism, over-commercialization, Brexit — you can lay them over the movies and they complement each other. They’re not Political films with a big ‘P’, but they’re clearly a reflection of society.”

Boyle is right: zombie stories have always mirrored our fears back at us. From Cold War paranoia to consumerism, from racial bigotry to environmental collapse, from pandemics to nativist panic, they’ve carried the weight of whatever society most dreads at that moment. And that thread of cultural projection stretches all the way back to the moment zombies first entered the American imagination.

When zombies initially shambled into our pop cultural consciousness, they reflected something slightly different: exoticism, colonialism, and one globe-trotting writer’s own morbid, insatiable appetites.

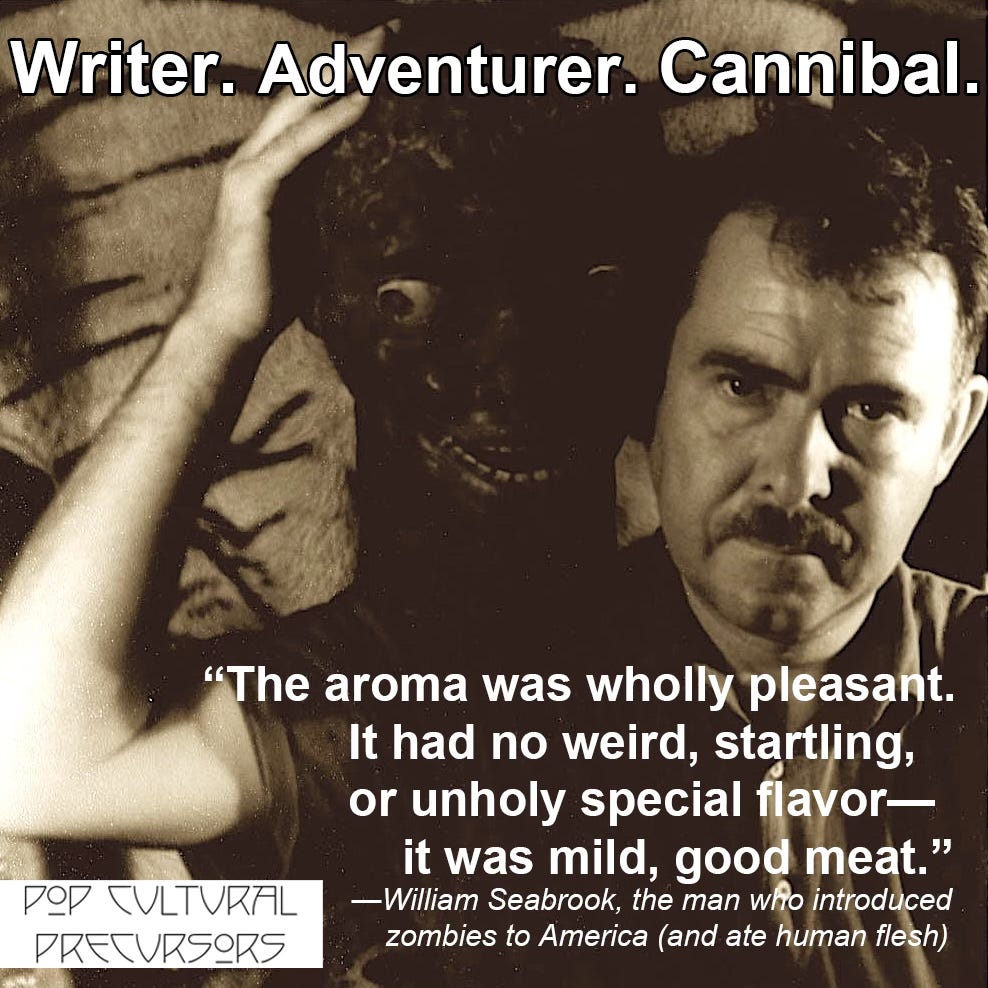

The journalist and travel writer William Seabrook introduced the term “zombie” to America after he learned of the mythical creatures during a visit to Haiti. He would go on to become a self-confessed cannibal who wrote about the smell, taste, and texture of freshly cooked human flesh with the relish of a restaurant critic.

His life story is fascinating—if you can stomach it. [This is an updated version of a previous post.]

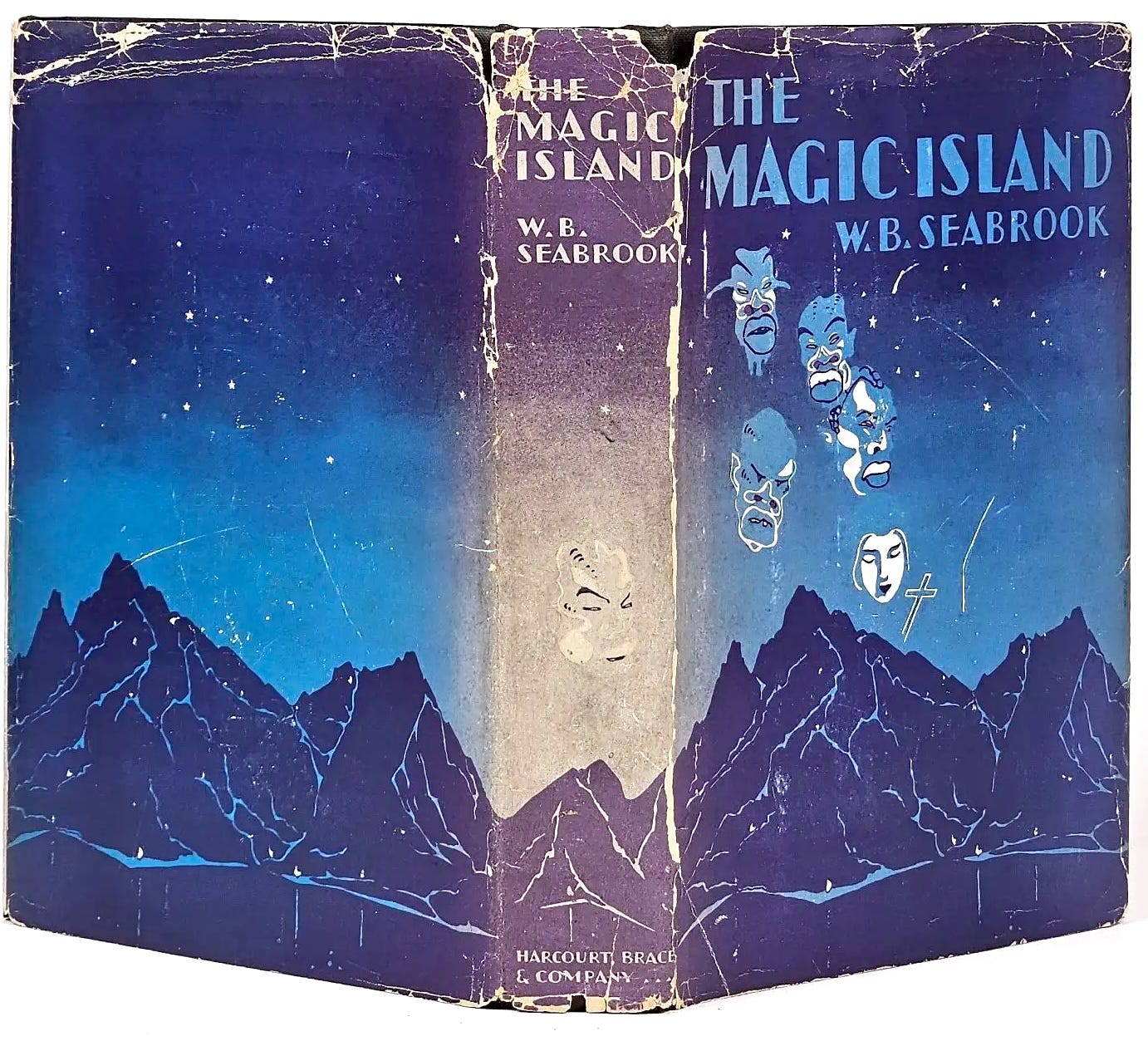

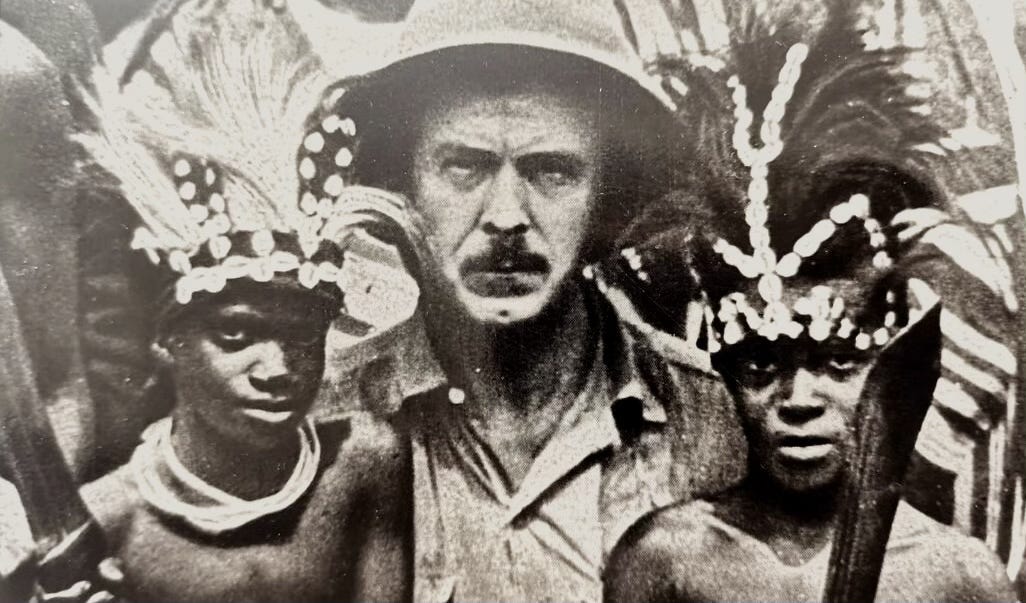

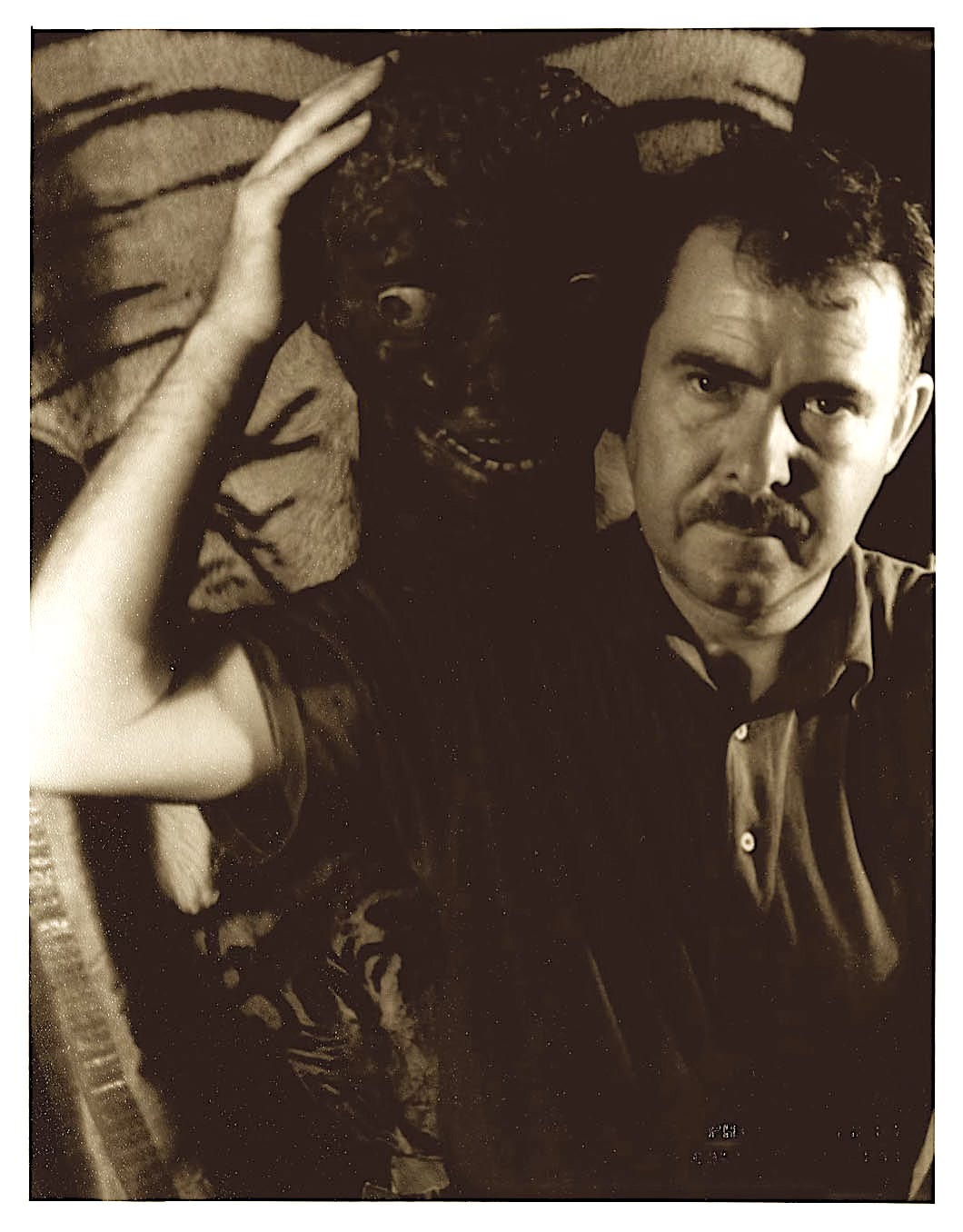

Seabrook was a bohemian, an occultist, a sadomasochist, and an amateur anthropologist who mixed high-minded literary aspirations with a knack for lurid sensationalism. In 1929, he released the book-length travelogue The Magic Island, in which he described Haitian culture and religious rituals

Seabrook prided himself on transcending the bigotry, conventionality, and superstitions of his upbringing in the Reconstruction-era South. He wanted to write about voodoo as dispassionately as he might write about Protestantism. But his book-length investigation of “black sorcery” seems incredibly racist and condescending in a modern light. (His writing in the book was accompanied by a series of illustrations by Alexander King that now seem equally offensive.)

“Endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life”

Here is how Seabrook says that the supernatural phenomenon of human reanimation was explained to him during his time in Haiti:

While the zombie came from the grave, it was neither a ghost, nor yet a person who had been raised like Lazarus from the dead. The zombie, they say, is a soulless human corpse, still dead, but taken from the grave and endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life—it is a dead body which is made to walk and act and move as if it were alive. People who have the power to do this go to a fresh grave, dig up the body before it has had time to rot, galvanize it into movement, and then make of it a servant or slave, occasionally for the commission of some crime, more often simply as a drudge around the habitation or the farm, setting it dull heavy tasks, and beating it like a dumb beast if it slackens.

Note that the idea of zombies as cannibals with an insatiable hunger for human flesh is completely absent from this formulation—that’s a more recent invention, with no connection to Haitian lore.

“Dead bodies walking, without souls or minds”

In The Magic Island, Seabrook explains what the actual dietary needs of the original zombies were reputed to be. He shares the story of a Haitian couple, Joseph and Croyance, who command a group of field workers that are “not living men and women but unhappy zombies who [they] had dragged from their peaceful graves to slave in the sun.” Croyance must prepare tasteless meals for them because zombies immediately die if they taste salt or meat. One day she takes pity on the “poor dead creatures who should be at rest,” and decides that it might cheer them to see the crowds and processions in the city during a religious festival.

So she tied a new bright-colored handkerchief around her head, aroused the zombies from the sleep that was scarcely different from waking, gave them their morning bowl of cold, unsalted plantains boiled in water, which they ate dumbly uncomplaining, and set out with them for the town. Croyance, in her bright kerchief, leading the nine dead men and women behind her, past the railroad crossing, where she murmured a prayer to Legba, past the great white-painted wooden Christ, who hung life-sized in the glaring sun, where she stopped to kneel and cross herself—but the poor zombies prayed neither to Papa Legba nor to Brother Jesus, for they were dead bodies walking, without souls or minds.

In town, Croyance slipped up and mistakenly fed salted pistachios to the zombies. The seasoned food broke the spell that had suspended them in an unnatural state between life and death; they all cried out, and then they each began to trudge towards the graveyards in their home villages. “No one dared stop them, for they were corpses walking in the sunlight, and they themselves and all the people know that they were corpses.”

When they reached their destinations, each of the zombies fell to the ground and immediately transformed into a pile of rotted flesh.

Seabrook records that he had several supposed zombies pointed out to him, but he eventually concluded, “Zombies were nothing but poor, ordinary demented human beings, idiots, forced to toil in the fields.” When the book was published, he felt that he had delivered a serious ethnographic study. But he was canny enough and cynical enough to play up the most exotic aspects of Haiti at every turn. And doing so helped to guarantee massive sales.

The mythos of voodoo and the idea of corpses reanimated by means of dark magic immediately struck a chord in American popular culture. Within a few years of the publication of The Magic Island, zombies had become a staple of the horror genre.

The spread of the zombie contagion

Many were eager to exploit the sudden fascination with the walking dead. A Broadway production called Zombie opened in early 1932. This “play of the tropics” was supposedly so bad that it closed almost immediately. It was restaged out of town as a comedy rather than a pulse-pounding thriller.

In June 1932, the pulp magazine Strange Tales Of Mystery And Terror published a short story “The House of the Magnolias.” It transplanted the zombie mythos to a plantation outside of New Orleans, with black zombies toiling through the night in the fields. A visitor took pity on them and fed them salted candy, releasing them from their cursed existence. But before these zombies returned to their graves, they took revenge on their slave master, burning the plantation house to the ground.

The original zombie mythos and the earliest zombie stories in American pop culture focused on the metaphor of slavery and forced labor. In July of 1932, White Zombie, the first zombie horror flick, was released. Bela Lugosi portrayed a voodoo priest named Murder Legendre who created an undead workforce to toil in his sugar mill.

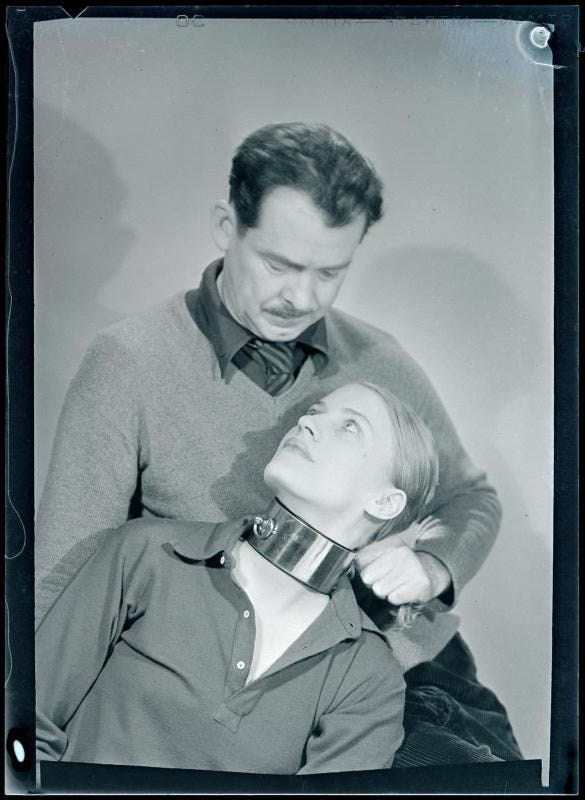

Seabrook himself was obsessed with captivity and subjugation throughout his life. He used a portion of the wealth that his zombie book brought him to hire women who would allow him to strip them naked, chain them up for days at a time, and force them to eat table scraps from the ground like an animal. He believed that the deprivation allowed them to enter a heightened psychic and spiritual state—it was all just part of his questing exploration of the outer limits of mysticism, you see. (He even wrote a book about it.)

The idea of zombies as violent creatures driven by an insatiable desire for human flesh wasn’t established until the 1968 release of Night of the Living Dead. The director George Romero never intended for his reanimated corpses to be seen as zombies, and the z-word is never used in the film. But the impact of this grisly low-budget masterpiece on the horror genre was so immense that cannibalism quickly fused with the Haitian mythos. Dead people attacking and devouring living people became the core trope of zombie lore.

But William Seabrook got to cannibalism first—decades before the Romero film’s release.

“No other man has written so fully, so amazingly, of cannibalism.”

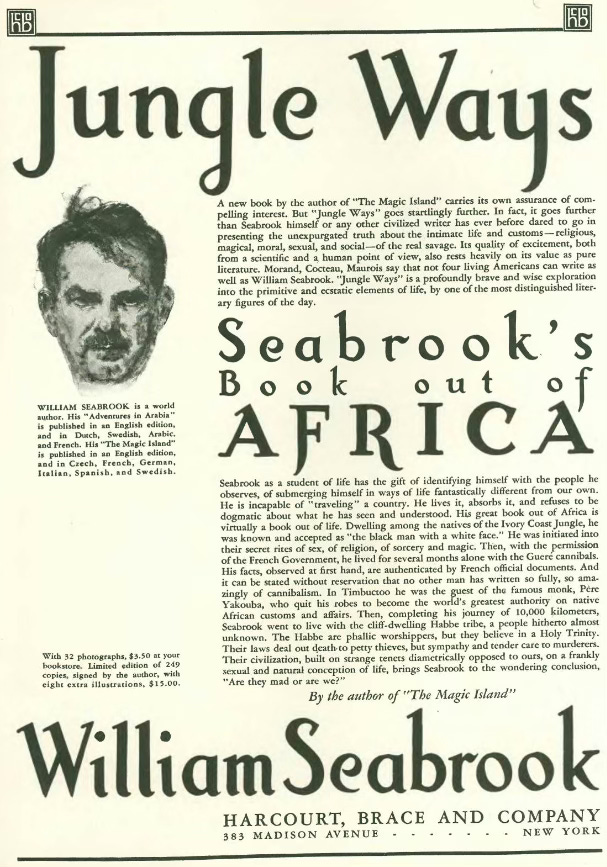

In 1930, Seabrook published the book Jungle Ways. Ads for it ran in distinguished publications like The New Yorker, and they read:

A new book by the author of “The Magic Island” carries its own assurance of compelling interest. But “Jungle Ways” goes startlingly further. In fact, it goes further than Seabrook himself or any other civilized writer has ever before dared to go in presenting the unexpurgated truth about the intimate life and customs — religious, magical, moral, sexual, and social — of the real savage. Its quality of excitement, both from a scientific and a human point of view, also rests heavily on its value as pure literature. Morand, Cocteau, Maurois say that not four living Americans can write as well as William Seabrook. “Jungle Ways” is a profoundly brave and wise exploration into the primitive and ecstatic elements of life, by one of the most distinguished literary figures of the day.

Seabrook as a student of life has the gift of identifying himself with the people he observes, of submerging himself in ways of life fantastically different from our own. He is incapable of “traveling” a country. He lives it, absorbs it, and refuses to be dogmatic about what he has seen and understood … With the permission of the French Government, he lived for several months alone with the Gueré cannibals, His facts, observed at first hand, are authenticated by French official documents. And it can be stated without reservation that no other man has written so fully, so amazingly, of cannibalism.

In Jungle Ways, Seabrook wrote openly, unashamedly—boastfully even—about eating human flesh. The writer’s fascination with the “exotic” rituals of African people (and the confidence that the book-buying public would reward him handsomely for doing so) compelled him to seek out a tribe that was reputed to have engaged in ritualistic cannibalism.

Seabrook wanted to explore the outer edges of human behavior, shatter taboos, and épater la bourgeoisie. And did he ever.

“I should like very much to try it myself, just once.”

While researching the Guere tribe in French West Africa, he concluded that cannibalism was unthinkable in Western cultures that “believe that in the essence of a man there is something holy which other animals have not.” But the Guere, like many cultures around the world, believe that everything has a soul and that it’s therefore unavoidable to eat things that contain the divine spark. Seabrook records his personal eureka moment about cannibalism:

I was compelled to say finally, “I can’t seem to think of any reason why you others shouldn’t eat it if you like it.” And I added, “As a matter of fact, I should like very much to try it myself, just once.”

“If you like it.” He reduces the practice to a mere food preference, as if these people were choosing between trout and pork chop on a restaurant menu.

For the Guere, cannibalism wasn’t a matter of sustenance. It had been part of an elaborate series of rituals that only took place in the context of a vanquished opponent in war. The Guere refused to let Seabrook, who had no connection to their culture or their beliefs, take part in their practice. In fact, they insisted that the practice had been discontinued long before his arrival.

At one point, the Guere gave in to the writer’s unceasing pestering and went through the motions of serving him a cannibal feast. The writer later deduced that they used subterfuge, feeding him ape meat.

But Seabrook didn’t let this deter him.

“The meat of a freshly killed man, who seemed to be about thirty years old”

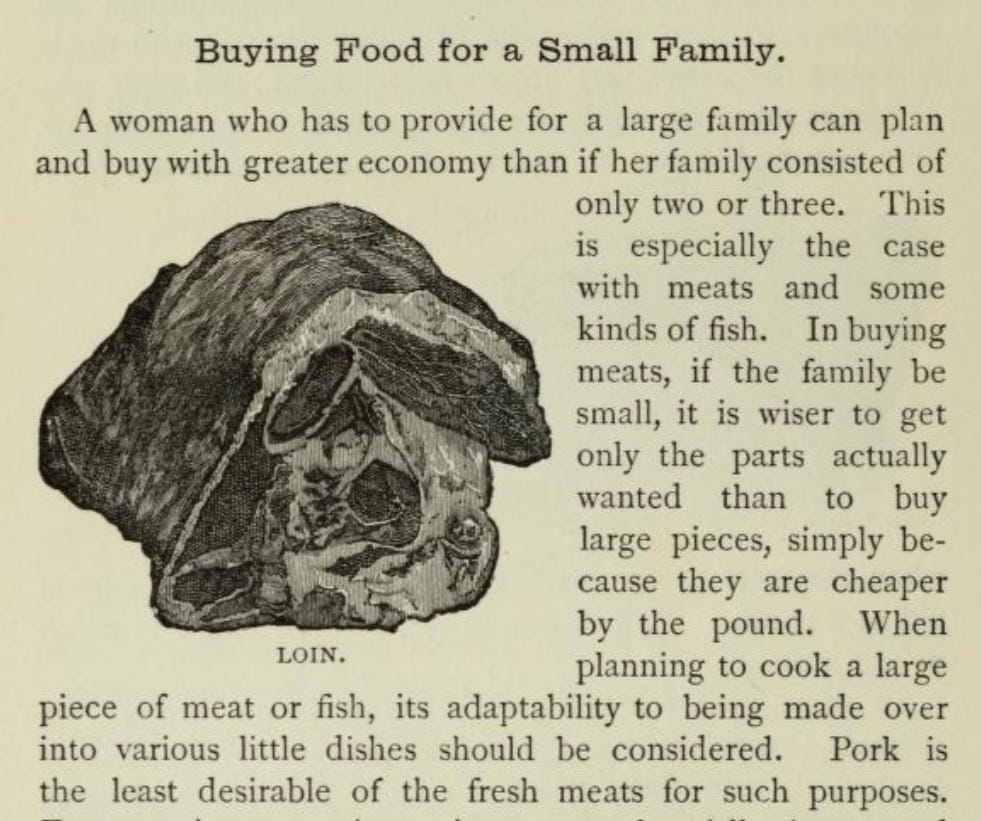

In Jungle Ways, the writer claims that he later managed to obtain some cuts of human flesh—small chunks of meat suitable for stew, “a sizeable rump steak, also a small loin roast.” He assured his readers that it was the result of an accidental death, “the meat of a freshly killed man, who seemed to be about thirty years old—and who had not been murdered.”

Seabrook was cagy about how he acquired this corpse flesh, and he insisted that it would be “unfair, unsporting, and ungrateful” to reveal the identity of whoever hooked him up. He would later reveal in his 1942 autobiography that an acquaintance obtained it for him from an internist at the Sorbonne who had access to the facility’s morgue.

In Jungle Ways, the writer explained how he prepared these cuts of human meat for consumption, spitting the loin roast, grilling the rump steak, and mixing the stew with rice.

He described the sensory experience of the cooking process at length:

The raw meat, in appearance, was firm, slightly coarse-textured rather than smooth. In raw texture, both to the eye and to the touch, it resembled good beef. In color, however, it was slightly less red than beef…the aroma was wholly pleasant, like those of beefsteak and roast beef, with no special other distinguishing odor…the fat was sizzling, becoming tender and yellower. Beyond what I have told, there was nothing special or unusual. It was nearly done and looked and smelled good to eat.

“It was like good fully developed veal, not young, but not yet beef”

Seabrook was determined to dine upon these pieces of a former person. And not just dainty little nibbles! “It would have been stupid to go to all this trouble and then taste too meticulously and with too much experimental nervousness only tiny morsels…I had thought about this and planned it for a long time, and now I was going to do it.”

The writer records that after he took his first bite, he was pleased and relieved to discover that he had no physical revulsion or moral compunctions about what he was doing. “It had no weird, startling, or unholy special flavor.” He went on to describe the taste and texture of human flesh in exacting, appalling detail.

“It was like good fully developed veal, not young, but not yet beef... It was mild, good meat with no other sharply defined or highly characteristic taste such as for instance, goat, high game, and pork have. The steak was slightly tougher than prime veal, a little stringy... The roast, from which I cut and ate a central slice, was tender, and in color, texture, smell as well as taste, strengthened my certainty that of all the meats we habitually know, veal is the one meat to which this meat is accurately comparable…A small helping of the stew might likewise have been veal stew, but the overabundance of red pepper was such that it conveyed no fine shading to a white palate.”

Of course, of course, he brings race into it again. And it’s so telling that a little bit of cayenne overwhelmed his gringo honky senses, but the moral issues of what he was doing never gave him pause. “Neither then nor at any time since have I had any serious personal qualms, either of digestion or of conscience,” he insists.

This unrepentant cannibalism was too much even for the sensation-starved public that had embraced Seabrook’s earlier tales of voodoo and zombies. In his 1942 autobiography, the writer quotes a review of Jungle Ways in the Montgomery Advertiser that captures the tenor of the public disgust: “It is not agreeable to think that an intelligent, educated member of the white race and of the American nation, has voluntarily descended to a scale lower than that observed by these lowly peoples.”

In Seabrook’s telling, he had been castigated and condemned for his broadmindedness and universalism, not for eating human flesh. “Those who might have forgiven me for eating a n——r couldn't forgive me for eating with one,” he wrote.

Seabrook knew that he would be remembered for his flirtation with cannibalism and for touching off the zombie craze, not for his lofty literary pretensions or his desire to be a world-bridging truth-teller. That tormented him, and he in turn tormented those around him. He became increasingly obsessed with alcohol and sadomasochism, and convinced several publishers to pay him to write about his experiences with both. Seabrook would die in 1944 after downing several handfuls of sleeping pills and a bottle of hooch. His former friend, the satanist Aleister Crowley, wrote, “The swine-dog W. B. Seabrook has killed himself at last.”

Seabrook was smart enough and self-aware enough to grasp that all of his vaunted taboo-busting had ultimately been about his own wealth, notoriety, and self-gratification.

READ MORE ABOUT IT:

William Seabrook. The Magic Island (1929)

William Seabrook. Jungle Ways (1930)

William Seabrook. No Hiding Place: An Autobiography (1942)

Marjorie Muir Worthington. The Strange World of Willie Seabrook (1966)

Emily Matchar. The Zombie King (2015, The Atavist Magazine, No. 45)

Joe Ollmann. The Abominable Mr. Seabrook (2017, graphic novel)

ELSEWHERE ON SUBSTACK:

In 1941, Seabrook released a book Witchcraft: Its Power in the World Today. As part of the promotional campaign, he and some fellow occultists held a “hex party” to curse Adolf Hitler with voodoo. Time Magazine was on hand to photograph the proceedings. Heather Woodward (Ashera) has the whole story here.

Horror Junkies writes an essay on why all horror—including zombie stories—is inherently political. Read it on HJTV PRESENTS! right here.

☭ notes from underground ☭ by L ★ has a fascinating essay on Vodou, Haiti, and the Colonial Aesthetics of Fear. You can read it here to get more context on its rich revolutionary history beyond the pop cultural appropriations.

HOLLOW, a journal of erotica in the arts, has a great piece on Man Ray, De Sade, Surrealism, and Bondage, which contextualizes the photo series “The Fantasies of Mr. Seabrook.” Read it here.

Daniel W. Drezner, cohost of the Space the Nation podcast, joins The Bulwark for a suitably wonky discussion of the undead, as well as his book Theories of International Politics and Zombies ( now available in a new updated Apocalypse Edition!). On his own newsletter Drezner’s World, Dan explains that The Last of Us is, in fact, a zombie show.

Frank 🎥 is sharing a carefully curated collection of classic films on Public Domain Movies. Among them: the original 1932 undead film, White Zombie. Read the essay about the film’s changing reputation, then watch it in its entirety here.

Freddie deBoer marks the release of 28 Days Later by castigating its creators for killing off supernatural zombies. You can read that on his eponymous Freddie deBoer newsletter here.

Raquel Castro reimprime un artículo fascinante sobre tomar en serio a los zombis, que apareció originalmente en la incomparable revista de ciencia Muy Interesante. Léelo AQUÍ.

"Boris Karloff portrayed a voodoo priest named Murder Legendre who created an undead workforce to toil in his sugar mill."

No- it was Bela Lugosi. In one of his best roles.