The First Movie Vampire Was a Woman

Before Dracula or Nosferatu, Theda Bara was "The Vamp," a sexy screen siren who fed on men

Most people believe that the classic 1922 film Nosferatu gave us the first iconic movie vampire. But any American in the silent film era would have said that the most famous cinematic vampire was Theda Bara.

Theda Bara’s film persona, established before the US entry into the First World War, was that of an irresistible seductress who lured unsuspecting men to their doom. They were powerless against her hypnotic eyes, her long dark hair, her molten passion. They gave up their lives, their reputations, and their careers for her, and she left them with nothing.

“The Arch-Torpedo of Domesticity”

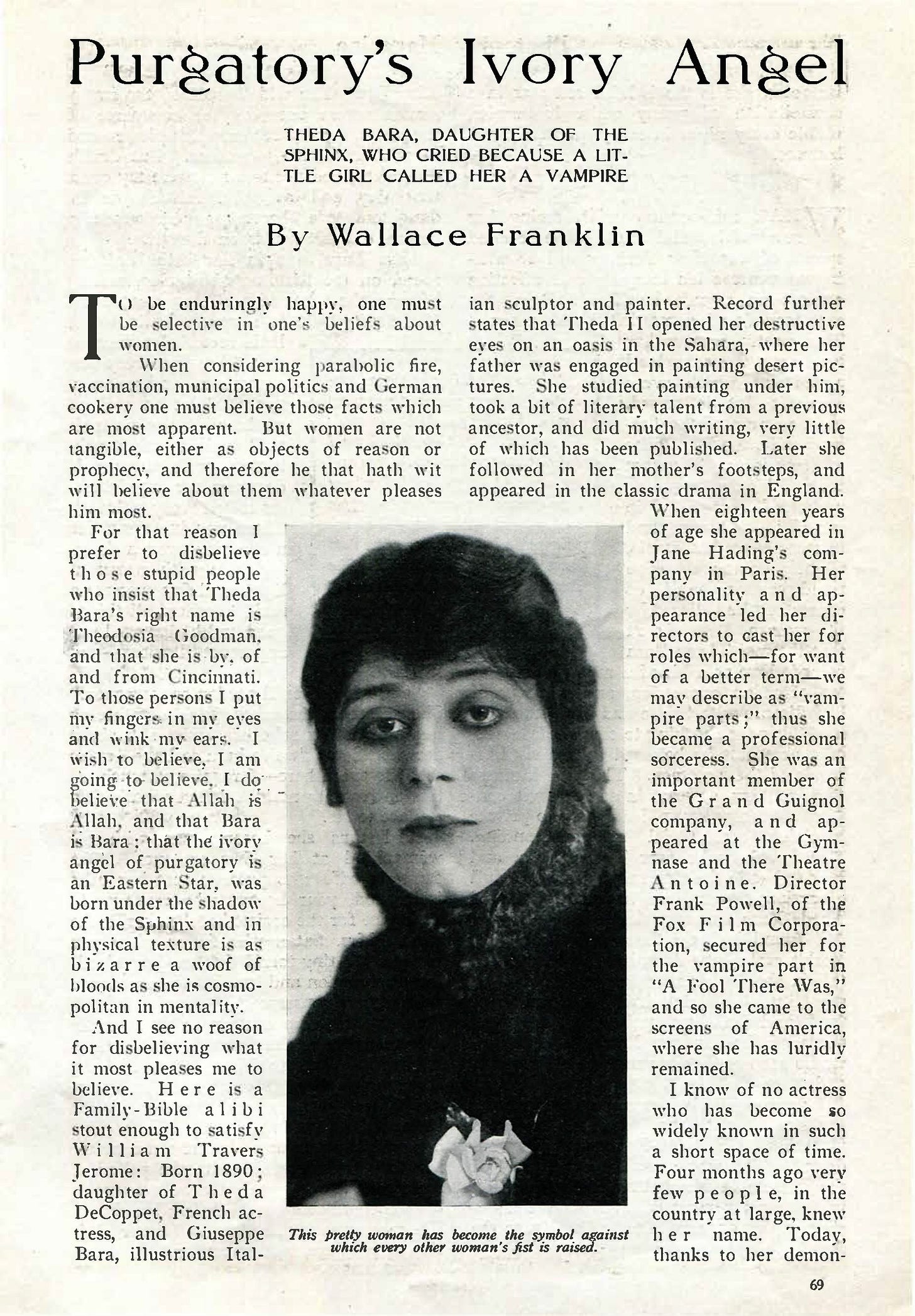

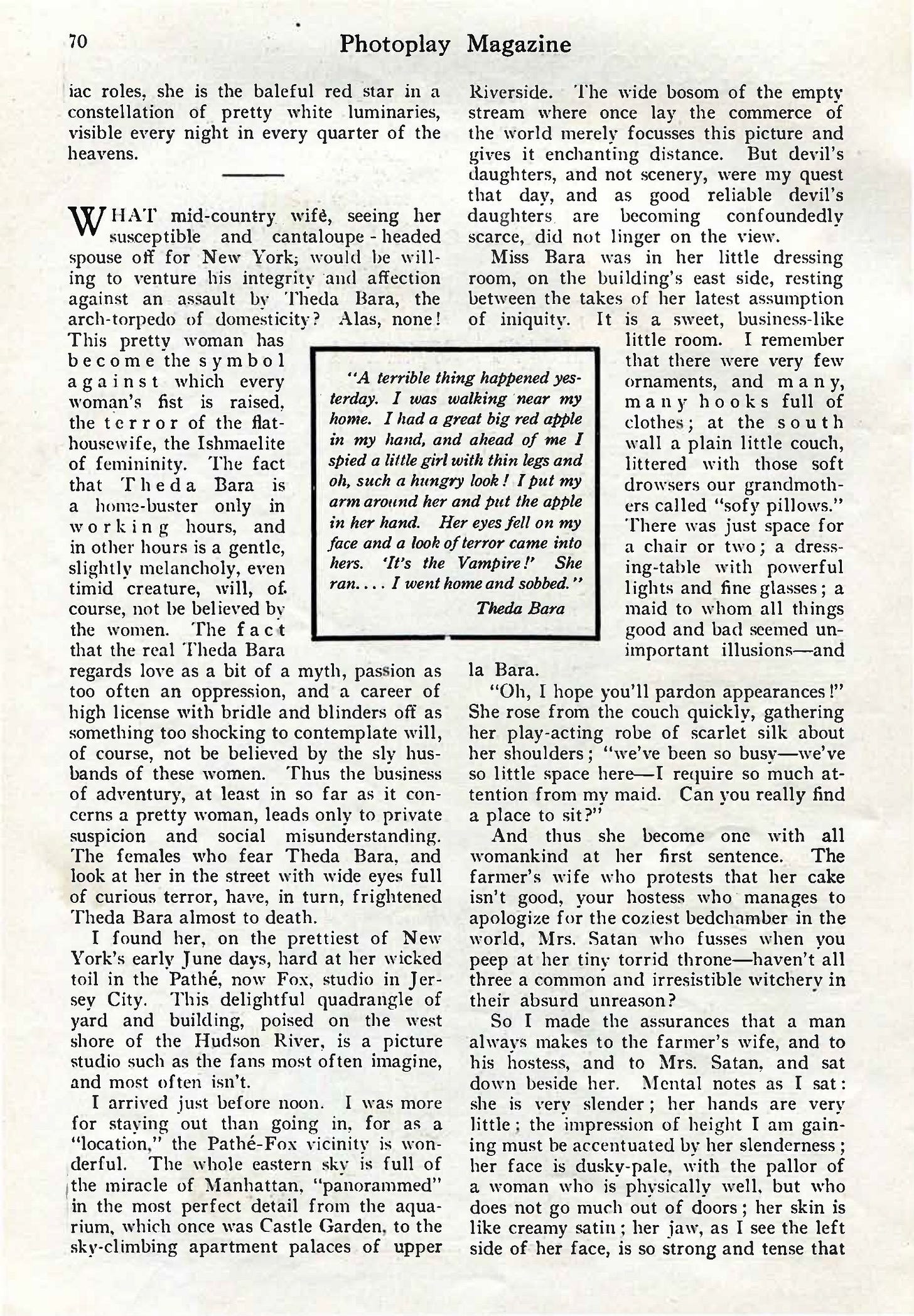

She sparked outrage, fear, and revulsion as well as fascination. “What mid-country wife, seeing her susceptible spouse off for New York would be willing to venture his integrity and affection against an assault by Theda Bara, the arch-torpedo of domesticity? Alas, none!” wrote Photoplay, America’s first major film fan magazine. “This pretty woman has become the symbol against which every woman’s fist is raised, the terror of the flathousewife, the Ishmaelite of femininity.” Like the biblical Ishmael, who was cast out and forced to wander the wilderness, Bara was an outsider. She portrayed a series of defiant, unrespectable women who refused to play by society’s rules.

In addition to being the first cinematic vampire, Bara was also the first person to have their life story rewritten to fit with their onscreen image. In the Golden Age of Hollywood, the phony bios were as carefully and artfully crafted as the films themselves.

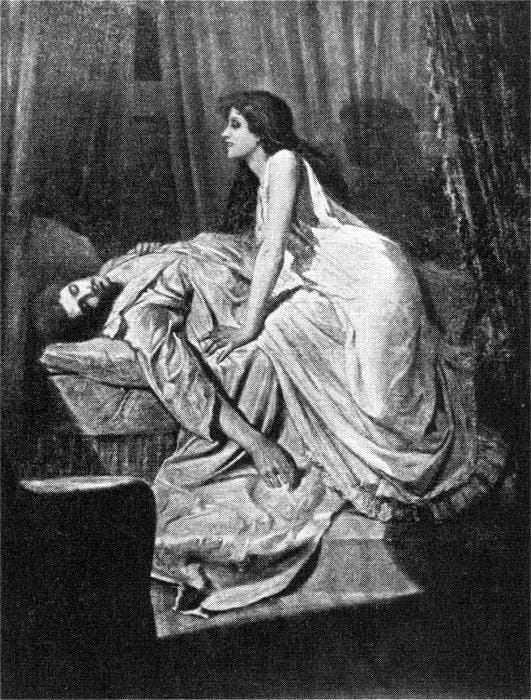

The Misogynist Origins of the “Vamp” Archetype

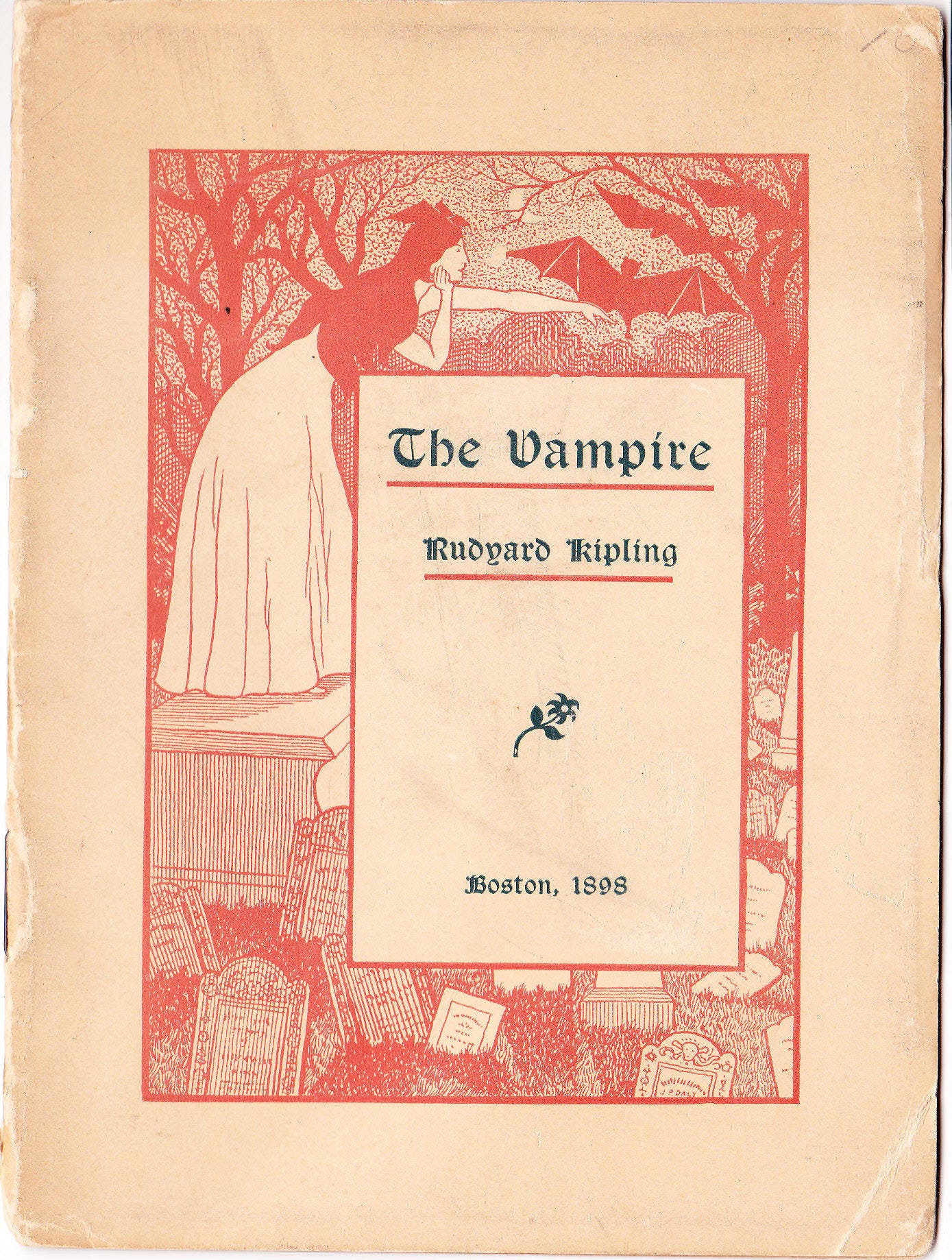

Several fictional works in the 1800s had popularized the idea of the vampyre or vampire as an undead, predatory villain. But by the end of the 19th century, the word came to be more commonly associated with a bewitching, seductive young woman. That’s because of Philip Burne-Jones. In 1897, the British Pre-Raphaelite artist painted an image of a woman gazing triumphantly at a man’s unconscious body. The man’s shirt is open and his throat and chest are exposed. Burne-Jones titled it “The Vampire.”

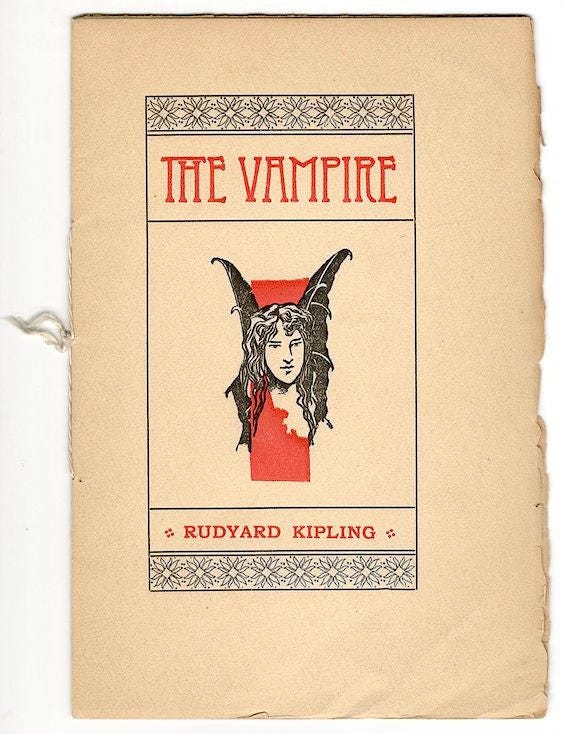

The writer Rudyard Kipling was Burne-Jones’ cousin. When “The Vampire” was displayed at the New Gallery in London, he was convinced to pen a promotional poem for the 1897 exhibition catalogue. You can read the whole thing here.

“We called her the woman who did not care”

“The Vampire” begins:

A fool there was and he made his prayer

(Even as you or I!)

To a rag and a bone and a hank of hair,

(We called her the woman who did not care),

But the fool he called her his lady fair—

(Even as you or I!)

Oh, the years we waste and the tears we waste,

And the work of our head and hand

Belong to the woman who did not know

(And now we know that she never could know)

And did not understand!

A fool there was and his goods he spent,

(Even as you or I!)

Honour and faith and a sure intent

(And it wasn't the least what the lady meant),

But a fool must follow his natural bent

(Even as you or I!)

...the fool was stripped to his foolish hide,

(Even as you or I!)

Which she might have seen when she threw him aside—

(But it isn’t on record the lady tried)

So some of him lived but the most of him died—

(Even as you or I!)The painting and the poem captured the public imagination, reproductions spread widely, and the phrase “a fool there was” entered the vernacular. They both appeared months after Bram Stoker’s Dracula was published. But Burne-Jones and Kipling’s riff on vampires had a far greater and more immediate impact on the culture than that genre-defining novel.

The commonly understood meaning of the word “vampire” came to be a sultry, predatory femme fatale who bewitched men and drained them of their life essence—and their folding money. That sense of the word survives in the shortened form “vamp.” Of course, adultery that leads to the male fool’s ruination is always and only the fault of a woman. The misogyny of the “vamp” archetype is self-evident.

“He was hers, soul, and body, and brain...”

A novel inspired by the poem was produced in 1909, and its prose is even purpler than you might imagine. Here’s an excerpt:

“Kiss me, My Fool!” The scarlet roses at her breast moved a little. Her lips were parted... Her eyes were on his...

He cried, thickly, agonizedly: “I’m free of you! Free, I tell you! I’m going back to wife—to child—to home—to honor! I’m free!”

Her lips curved. Her breast heaved. Her arms glowed. And her eyes were on his... He came a step nearer—another step—yet another... He was nearer, now... She leaned back a little, in the great chair...

He was not a man, now. He was a Thing, and that Thing was of her. Hands hung slack, loose, at his sides; jaw drooped; lips were pendulous. Only, in his eyes was that light that she, and she alone, knew how to kindle... He was hers, soul, and body, and brain...

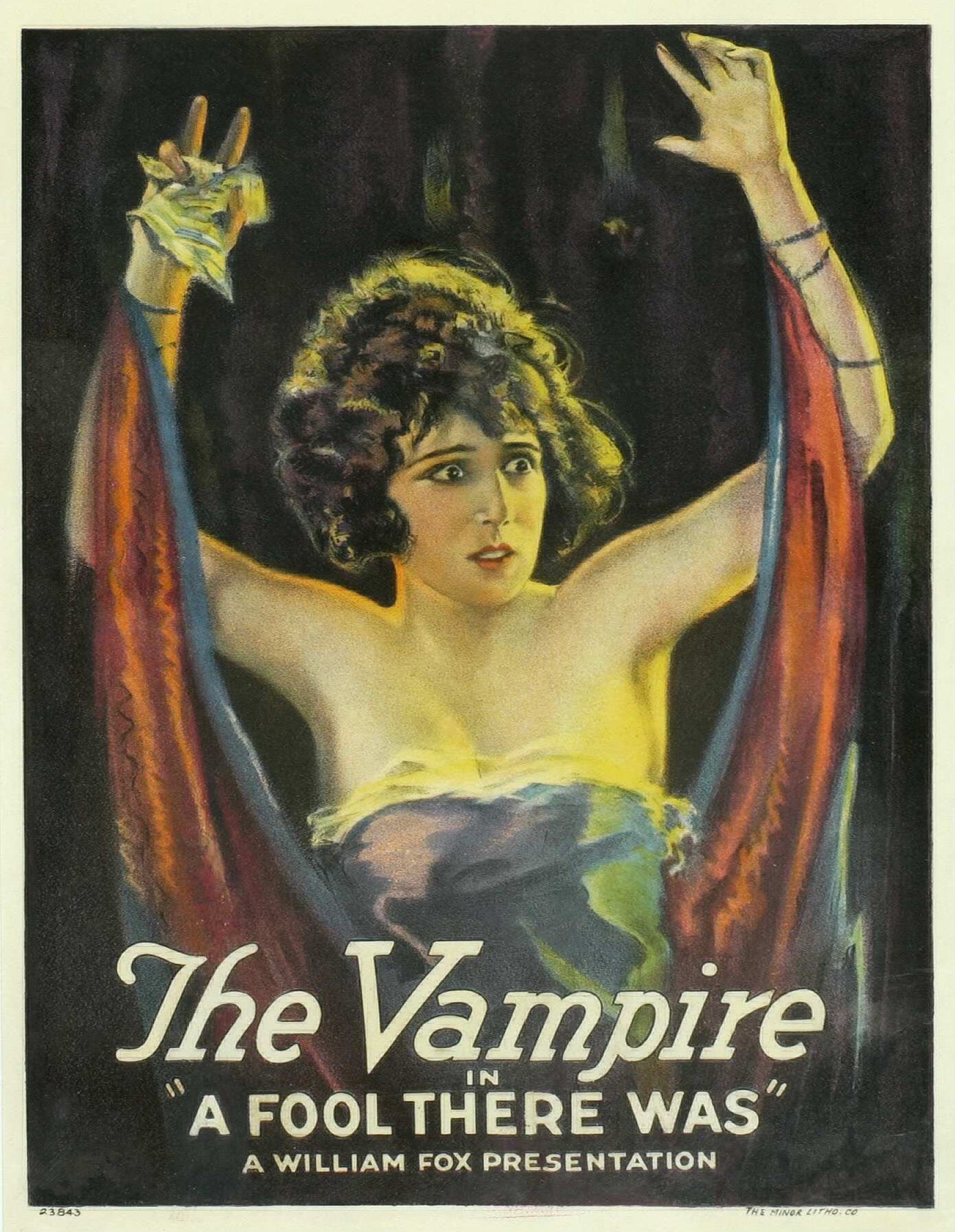

A stage adaptation of the poem by the same author was a smash hit on Broadway, and in 1915, the producer William Fox acquired the rights to turn that play into a film. The film version of “A Fool There Was” was a smash hit. It would also spawn the first cinematic sex symbol, whose fame was fed by the first modern movie studio publicity campaign.

Manufacturing the first cinematic star persona

The incomparable humorist S.J. Perelman wrote a piece for the New Yorker in the 1950s about the indelible impact that Bara’s scandalous onscreen image had on popular culture, and on his 11-year-old self:

I accidentally got my first intimation of Miss Bara from a couple of teachers excitedly discussing her. “If you rearrange the letters in her name, they spell ‘Arab Death,’” one of them was saying, with a delicious shudder. “I’ve never seen an actress kiss the way she does. She just sort of glues herself onto a man and drains the strength out of him.”

“I know—isn’t it revolting?” sighed the other rapturously. “Let’s go see her again tonight!”

Needless to add, I was in the theater before either of them, and my reaction was no less fervent. For a full month afterward, I gave myself up to fantasies in which I lay with my head pillowed in the seductress’s lap, intoxicated by coal-black eyes smoldering with belladonna. At her bidding, I eschewed family, social position, my brilliant career—a rather hazy combination of African explorer and private sleuth—to follow her to the ends of the earth. I saw myself, oblivious of everything but the nectar of her lips, being cashiered for cheating at cards (I was also a major in the Horse Dragoons), descending to drugs, and ultimately winding up as a beachcomber in the South Seas.

The fact that Theda Bara’s name was an anagram for “Arab Death” was deliberately injected into the national conversation by Fox Film publicists. Those publicists also concocted Bara’s Egyptian heritage out of whole cloth. It was a foundational example of Hollywood Orientalism: borrowing vague “Eastern” mystique to make a white woman from the Midwest seem more dangerously alluring.

In fact, the publicists are the ones who bestowed the name “Theda Bara” on her.

Bara was born Theodosia Goodman in Cincinnati. (She was named after Aaron Burr’s ill-fated daughter.) Her father was a Polish immigrant who became a tailor, and her mother was a salesgirl who rose to become co-owner of Dunkelmeyer & DeCoppet Wigmakers. People who knew Theodosia growing up said she was a “nice Jewish girl.” She caught the acting bug, and after an unsuccessful attempt at a career on the stage in New York City, she shifted her efforts to the city’s nascent film industry. She lied about her age to secure a contract with the newly formed Fox Pictures, claiming she was 22. When the filming of A Fool There Was commenced, she was actually 29.

Filming A Fool There Was was a miserable experience for Bara. This was long before the era when stars received private trailers and attentive assistants. Her contract required her to supply her own costumes—a typical arrangement at the time. Primitive film stock required her to cake her face in thick yellow makeup and brown lipstick to have the desired skin tones on screen.

She later recalled the humiliation of filming in a public street, dressed in gaudy gowns with panther skin and gold leaf, over-emoting wildly through all of that heavy clown paint. (Karina Longworth’s You Must Remember This podcast episode about Bara has great insights into the production process and the acting style of the era.)

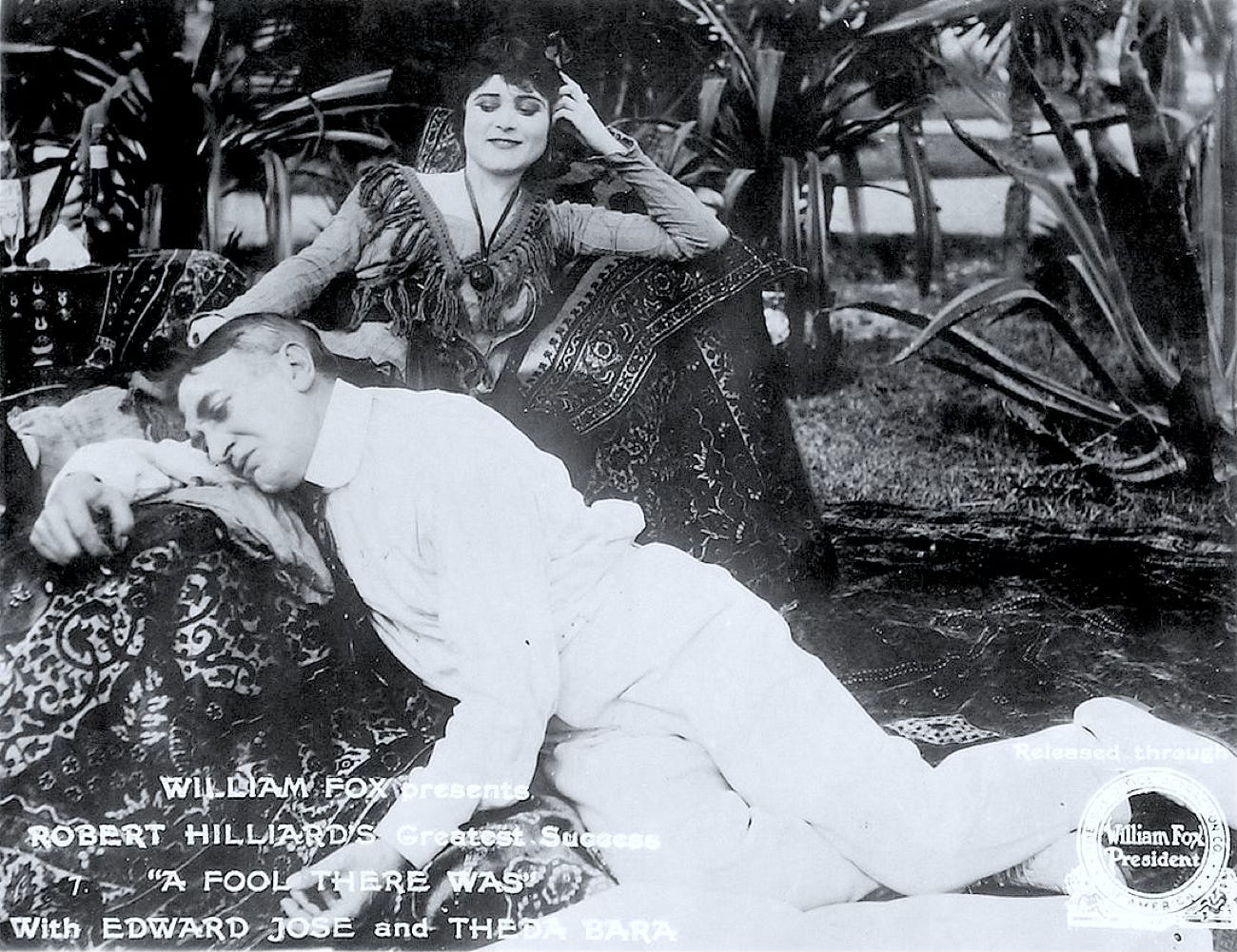

Bara is listed in the credits as simply “The Vampire,” occasionally shortened in the title cards to “The Vamp.”

“Kiss me, my fool!”

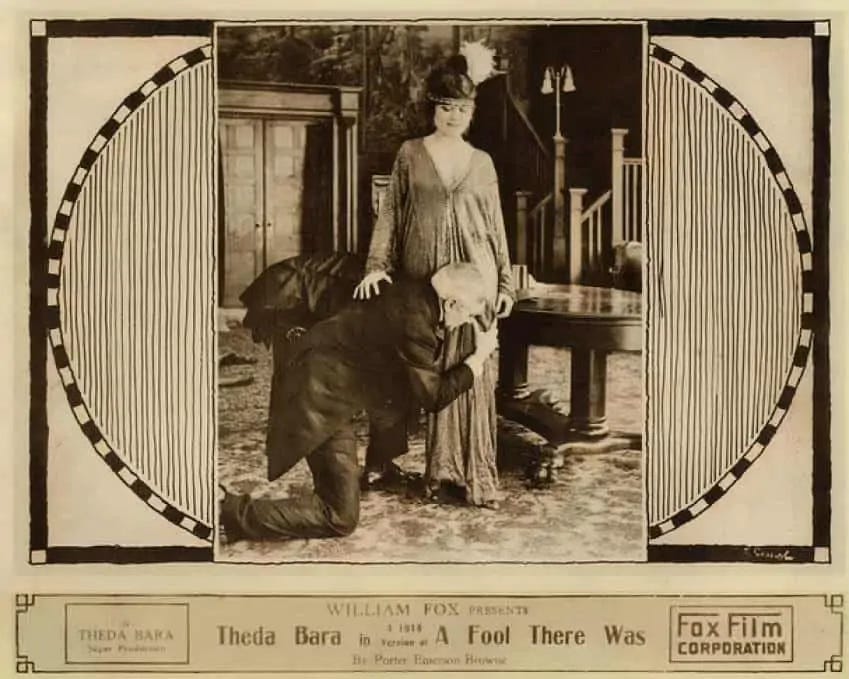

The high point of the film is when Bara is accosted by a former lover: he gesticulates wildly to express his anguish and rage and despair, and then he produces a gun and points it at her. The Vampire looks at the gun, chuckles mirthlessly, and swats it away with a flower she clutches. Then she fixes her hypnotic, kohl-rimmed eyes on her prey, moves her face towards his, and mouths the immortal line, “Kiss me, my fool!” He instead points the gun at his own head and ends his misery. Minutes after his suicide, The Vamp is seducing another unwary victim by wantonly flashing some hot, hot ankle. (Watch the clip below.)

The film ends with The Vampire’s latest victim reduced to a pitiful husk. His hair has turned white; he’s lost his career, his family, his reputation, and his self-respect. The man’s ever-faithful wife attempts to free him from the clutches of the foul temptress, but the rescue efforts are in vain. With a sexual aggressiveness that would have been shocking and unprecedented to the audience of the time, The Vampire darts forward and kisses her escaping prey like she is sucking the last remnants of his soul from his body. (Watch the clip below.)

Soon after, he collapses to the floor. The intertitles give us a few final snippets of the Kipling poem: “The fool was stripped to his foolish hide… some of him lived but the most of him died.” Bara recreates the pose from the Philip Burne-Jones painting that inspired the film, and gloats over his motionless body as she dribbles rose petals on his face.

The Media Campaign Behind “The Vamp”

Bara was brilliant in A Fool There Was; the movie surrounding her towering performance was unremarkable and stagy. But the way that film was marketed was revolutionary. The fledgling Fox Film Corporation tasked its new publicity department, staffed by former New York World reporters, with fabricating an exotic backstory for the Polish-American actress who’d had a brief and unsuccessful theater career in New York.

At a press conference for A Fool There Was in January 1915, the assembled journalists were told that Bara was the Serpent of the Nile, born in the Sahara to a French actress mother and an Italian sculptor father, and raised “in the shadow of the Sphinx.”

“Thus she became a professional sorceress”

The publicists said she had been a star of the stage in France, forced to flee to America due to the outbreak of WWII. They wrote that she was the reincarnation of Circe, Delilah, and all of the wickedest women in myth and history. They hinted that Miss Arab Death possessed supernatural powers and arcane talismans that helped her cast a spell on her victims…and the viewing public.

Photoplay reported that Bara:

“opened her destructive eye on an oasis in the Sahara, where her father was engaged in painting desert pictures … Later she followed in her mother’s footsteps, and appeared in the classic drama in England. Her personality and appearance led her directors to cast her for roles which—for want of a better term—we may describe as ‘vampire parts;’ thus she became a professional sorceress.”

The Washington Times also printed the fanciful biography as fact.

The motion picture patrons of Washington have recently had opportunity

to see one of the most famous or French actresses, Theda Bara, In the

part of the “vampire” woman in the film production of “A Fool There Was,”

… But few of the picture patrons know that Miss Bara has for several seasons been considered one of the greatest actresses on the European stage, and for some time

was the leading woman at the Théâtre Antoine in Paris, where plays filled with

thrills were produced for literary and artistic Europe … She is strikingly beautiful, with brilliant dark eyes and the rich coloring that goes with the pure brunette type. She has been for years known as an interpreter of dramatic masterpieces that were regarded as extremely difficult or impossible for any other actress.

“Never have I gazed into a face portraying such wickedness and evil”

A Fool There Was became a tremendous box office hit. Almost immediately, Bara became one of the biggest stars of the silent era, and touched off the stratospheric rise of Fox Film, which would later become 20th Century Fox. Her fame was rivaled only by Charlie Chaplin and that goody-two-shoes Mary Pickford. Bara was happy to play along with the vamp image, wearing veils and black clothing and slathering on makeup.

Bara played along with the invented backstory dreamed up by studio publicists. For press events, Fox encouraged her to use an exotic accent and profess her interest in mysticism and the occult. Bara would laugh uproariously when she encountered the latest bit of invention printed about her in the papers—one item described a 2,000-year-old emerald ring supposedly given to her by a blind, wizened old sheik.

The studio hired Emily H. Vaught, New York Society Phrenologist and Physiognomist, to determine the screen star’s character based on the shape of her head and her facial features:

I write this with a photograph of Theda Bara, the William Fox “Vampire,” before me. Never in all my experience as a professional character reader have I gazed into a face portraying such wickedness and evil—characteristics of the vampire and the sorceress.

Theda Bara belongs to what we term the wide-faced, muscular type of people, whose bones are slender and small, and who are governed by the same muscular system as the serpent. They are sinuous like the serpent, and, as if the characteristics of a reptile were not enough, they have a feline temperament, deliberately taking pains to inflict suffering on others.

No publicity stunt was too on the nose for the Fox publicists staging The Vampire campaign. Bara even posed with skeletons for publicity photos.

“Her hair is like the serpent locks of Medusa, her eyes have the cruel cunning of Lucretia Borgia”

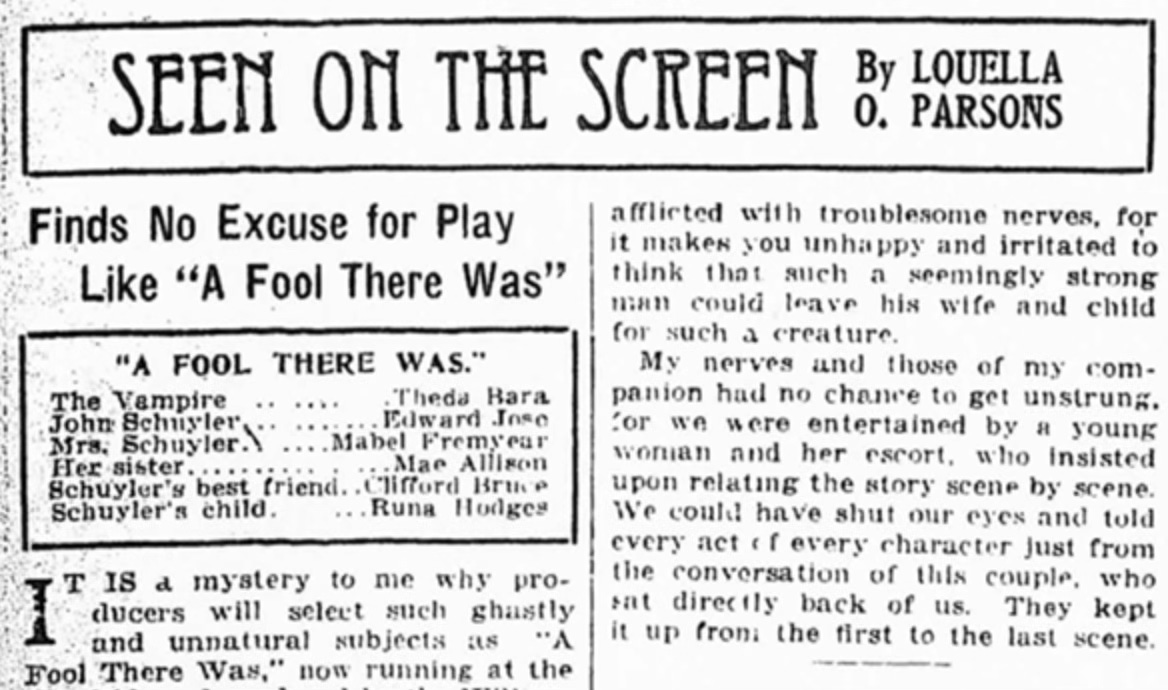

The screenwriter and early film critic Louella Parsons’ initial review of A Fool There Was in the Chicago Record-Herald was all dudgeon and disapproval.

“The picture is appalling in its grewsome unreality. In the first place no steady-going, level-headed business man, with sweet wife and adorable “kiddie” would be led astray by a woman so palpably common. A more subtle. refined character might appeal to his senses, but never could this coarse creature lure a man away from his home … Theda Bara, the vampire, while very handsome gave almost too harsh an impersonation to this unpleasant character ... it makes you unhappy and irritated to think that such a seemingly strong man could leave his wife and child for such a creature.”

But Parsons was on hand to see Fox’s ludicrous Chicago press event, and she was also invited to interview Bara “out of character.” The columnist quickly saw the value of playing along with the studio’s invented backstory, in a way that let her play her own role—that of the clever truth-teller who was in on the joke.

Parsons would go on to become one of the foremost film columnists in the country, and one of the most powerful women in Hollywood. Here is how she later wrote about Bara, clearly delighting in the awfulness of an onscreen image that had recently revolted her. She’d learned to stop hectoring and love The Vampire.

“Her hair is like the serpent locks of Medusa, her eyes have the cruel cunning of Lucretia Borgia . . . and her hands are those of the blood-bathing Elizabeth Bathory, who slaughtered young girls that she might bathe in their life blood and so retain her beauty. Can it be that fate has reincarnated in Theda Bara the souls of these monsters of medieval times?”

“Scientists have questioned this most extraordinary of women to secure fresh evidence to support their half-proved laws of transmigration of souls, but the result has only been to prove that, though Miss Bara is the greatest delineator of evil types on the stage or screen today, she is in real life a sweet wholesome woman who detests the abnormal.”

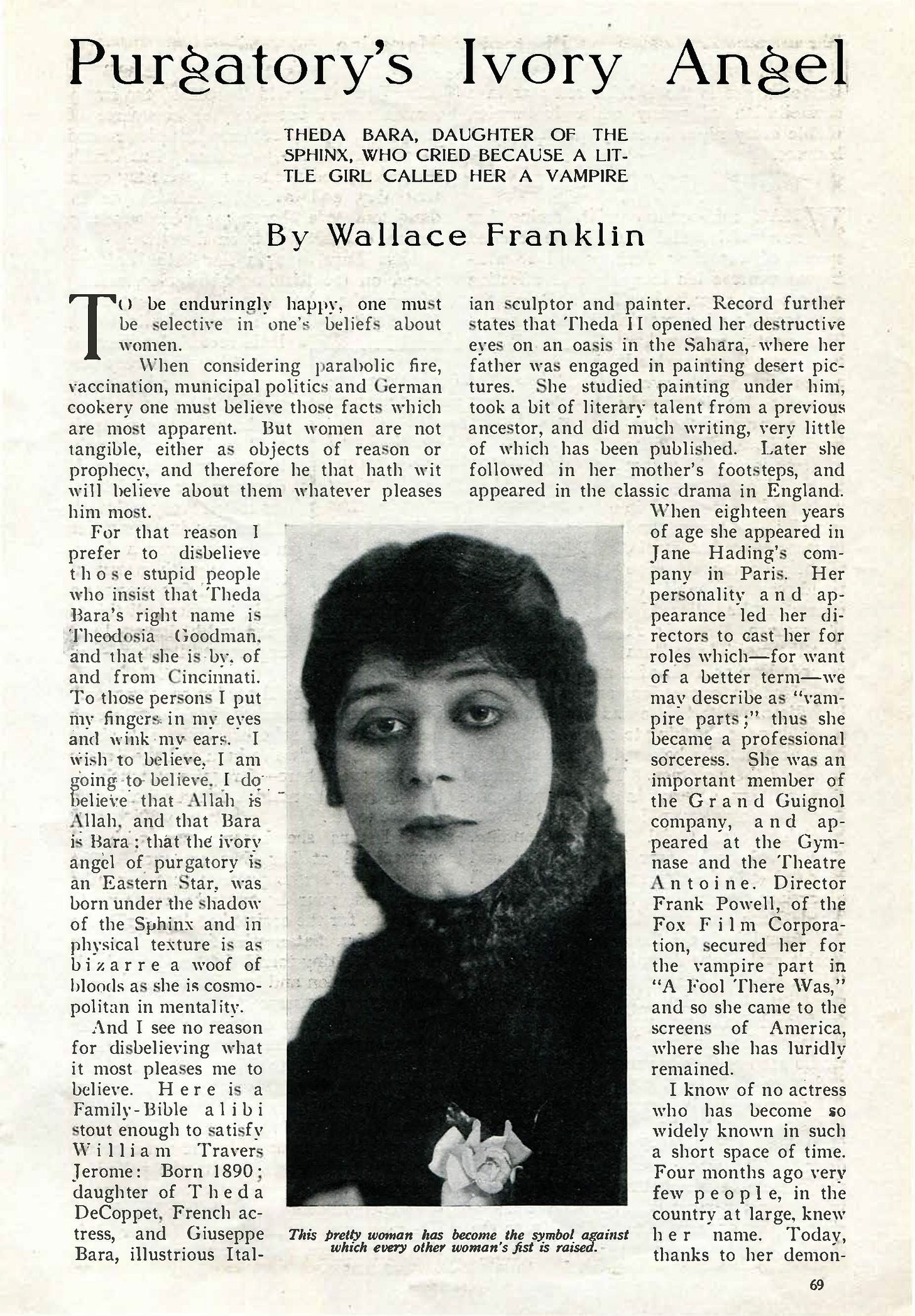

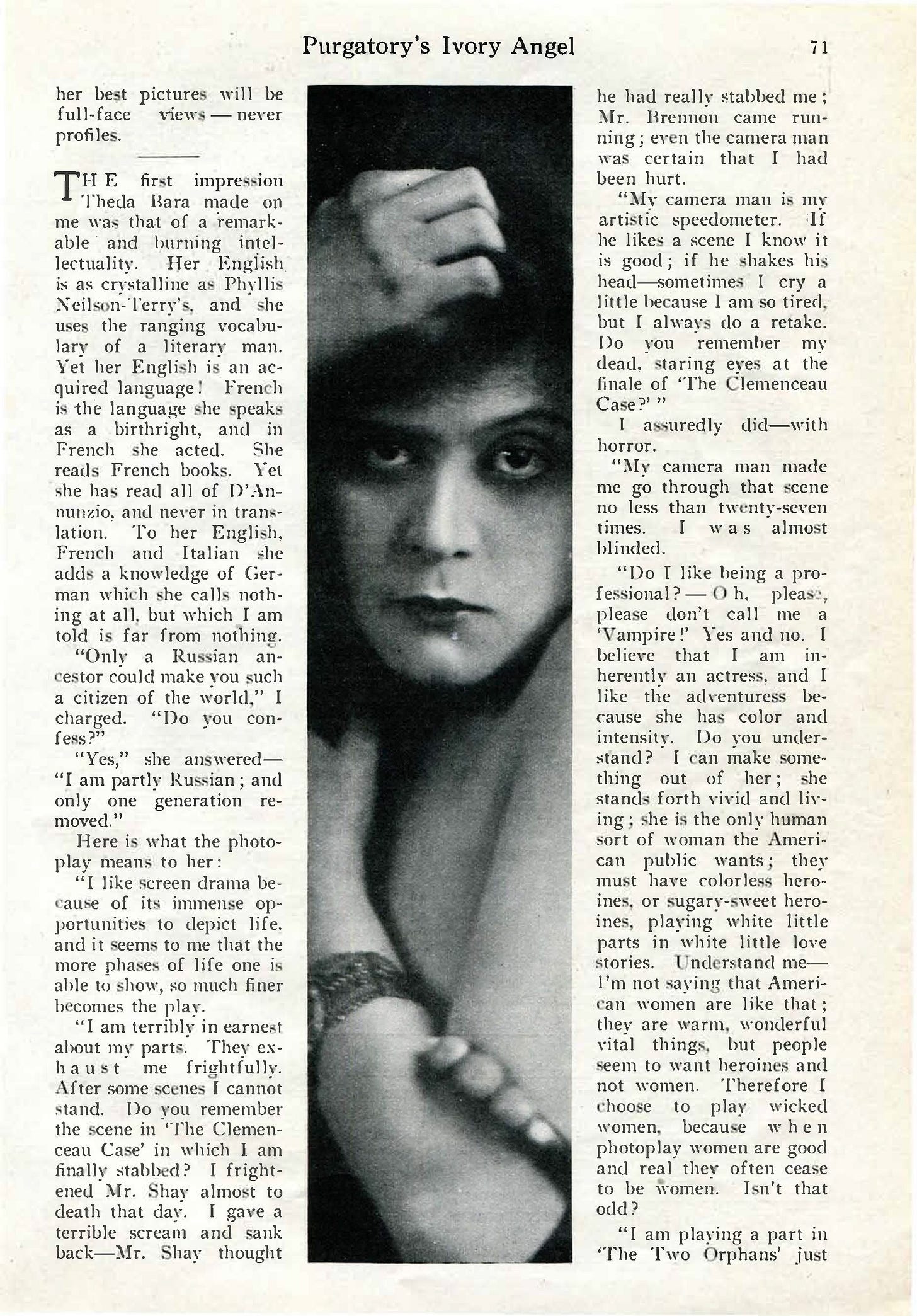

The September 1915 issue of Photoplay published “a visit with Theda Bara, tender-hearted vampire.” Dubbing her “purgatory’s ivory angel,” it laid out exactly how the enthusiast press would debunk her vampire origin story while also reveling in it.

“I prefer to disbelieve those stupid people who insist that Theda Bara’s right name is Theodosia Goodman, and that she is by, of and from Cincinnati,” wrote Wallace Franklin in Photoplay. “To those persons I put my fingers in my eyes and wink my ears. I wish to believe, I am going to believe, I do believe that Allah is Allah and that Bara is Bara … I see no reason for disbelieving what it most pleases me to believe.” (I’ve included full text of this article at the end of this post.)

“She is the only human sort of Woman the American public wants”

Bara does the interview straight, as Theodosia Goodman, not as the daughter of the Sphinx. The actress confesses to the Photoplay interviewer that she is about to turn 30—a surprising confidence, as just months before she had lied about her age to William Fox and claimed she was in her early twenties so that she would not be rejected as over-the-hill.

Many have argued over whether Bara’s persona was that of an empowered and sexually liberated proto-feminist (or more plausibly) an appallingly sexist embodiment of slut-shaming. In the Photoplay interview, Bara is admirably clear-eyed about the fact that what she likes about her onscreen image is that it allows her to play the kinds of interesting, meaty roles that were extremely scarce for women at the time. “Oh, please, please don’t call me a ‘Vampire!’” she tells the interviewer, preferring the word “adventuress” for her onscreen identity:

“I like the adventuress because she has color and intensity. Do you understand? I can make something out of her; she stands forth vivid and living. She is the only human sort of Woman the American public wants; they must have colorless heroines or sugary-sweet heroines playing white little parts in white little love stories. Understand me—I’m not saying that American women are like that; they are warm wonderful vital things: but people seem to want heroines and not women. Therefore I choose to play wicked women because when photoplay women are good and real they often cease to be women. Isn’t that odd?”

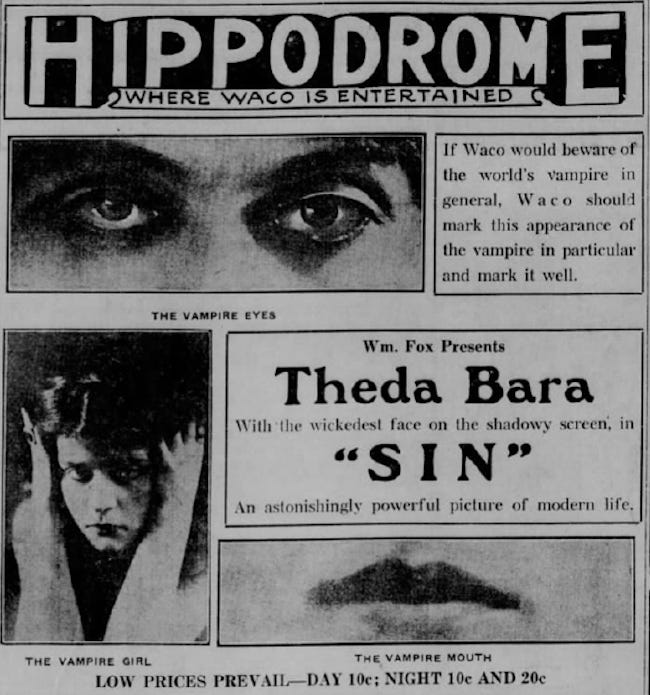

The Vampire would go on to crank out ten movies before the end of 1915. Production schedules were tighter back then and the performers were made of sterner stuff. (She says she often wept with exhaustion on set in the Photoplay interview.) The titles of her films released that year say it all: Destruction, Carmen, The Devil’s Daughter, The Galley Slave, and the admirably blunt Sin. A news item promoting that film refers to Bara as “the world’s vampire … with the wickedest face on the shadowy screen.”

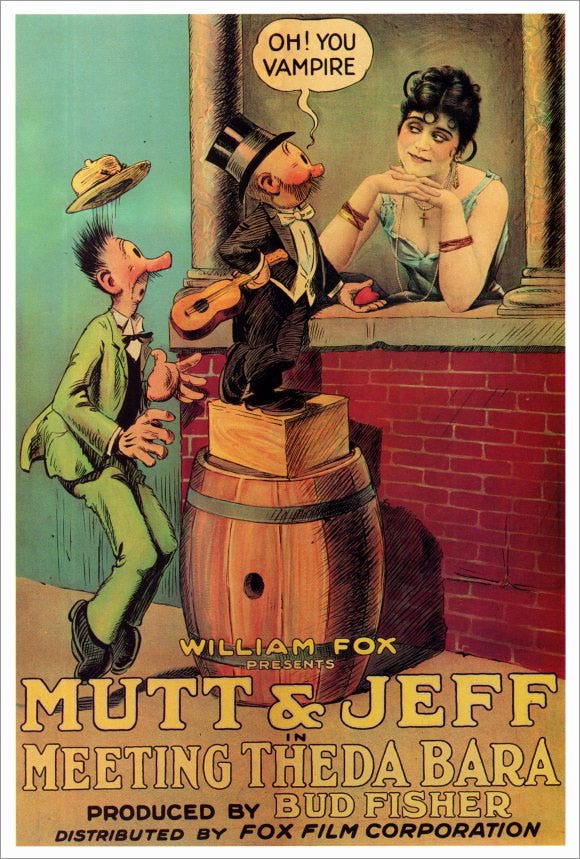

Bara made scores more films over the next few years, often wearing outfits onscreen that even today would be considered revealing. The titles and subject matter also got even more daring: The Forbidden Path, When a Woman Sins, The Tiger Woman, Her Double Life, The Siren’s Song.

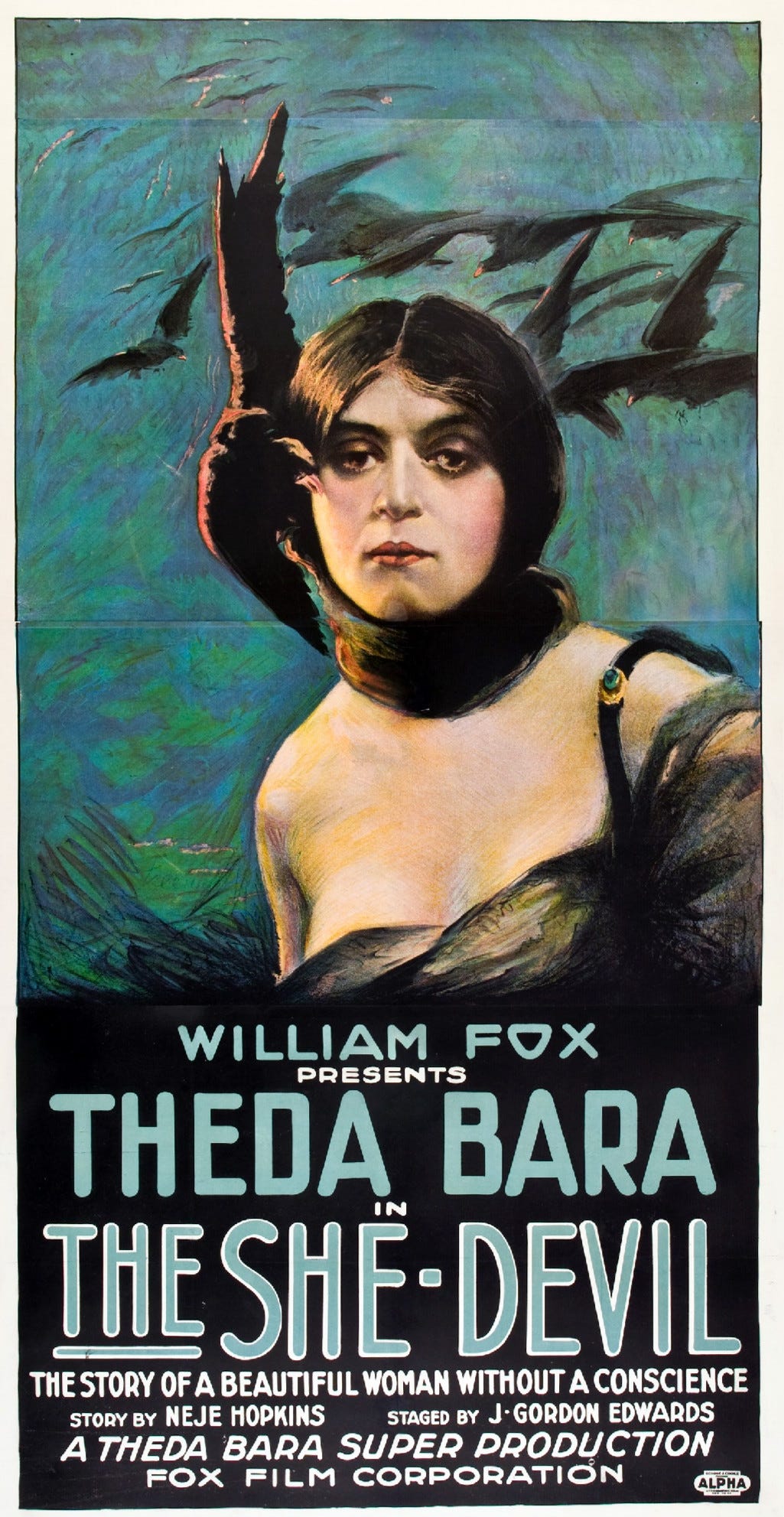

I can’t resist, here are still more film titles: The She-Devil, The Unchastened Woman, The Vixen, When Men Desire, and The Eternal Sappho.

She was such a box office draw that she negotiated a contract that earned her the then-unheard-of sum of thousands of dollars a week. She also increasingly bridled at being typecast, and demanded the chance to occasionally play a good girl, and the producers had no choice but to acquiesce to keep their star happy. But those films always disappointed, either because the public didn’t want them or because the studio refused to promote them.

Bara’s Career Decline and the Rise of Bloodsucking Undead Movie Vampires

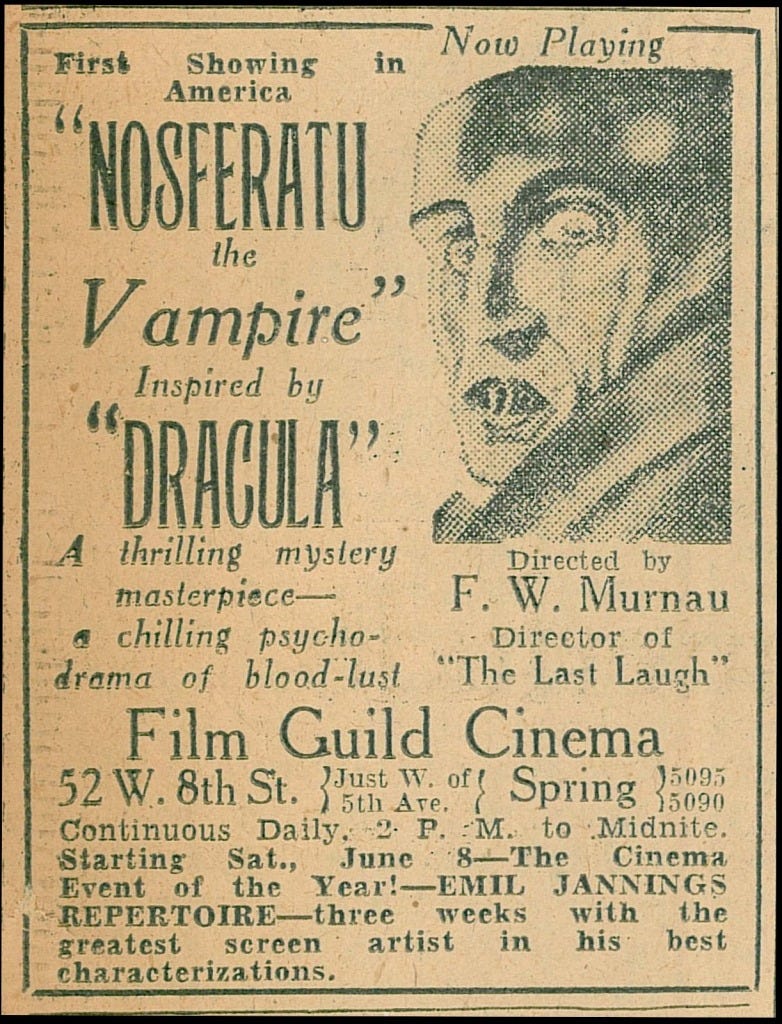

In 1922, F. W. Murnau’s German Expressionist masterpiece Nosferatu would establish the paradigm for the movie vampire as we now know it. The film wasn’t screened in America until 1929 due to a lawsuit from Bram Stoker’s estate—the film was clearly an unlicensed adaptation of the novel Dracula, with character names and locale changed. But by the mid-1920s, Bara’s film career was over. A more slender flapper-style female form was in vogue, and audiences became accustomed to more subtle characterizations. The histrionic acting style of the early silents that Bara excelled at was passé.

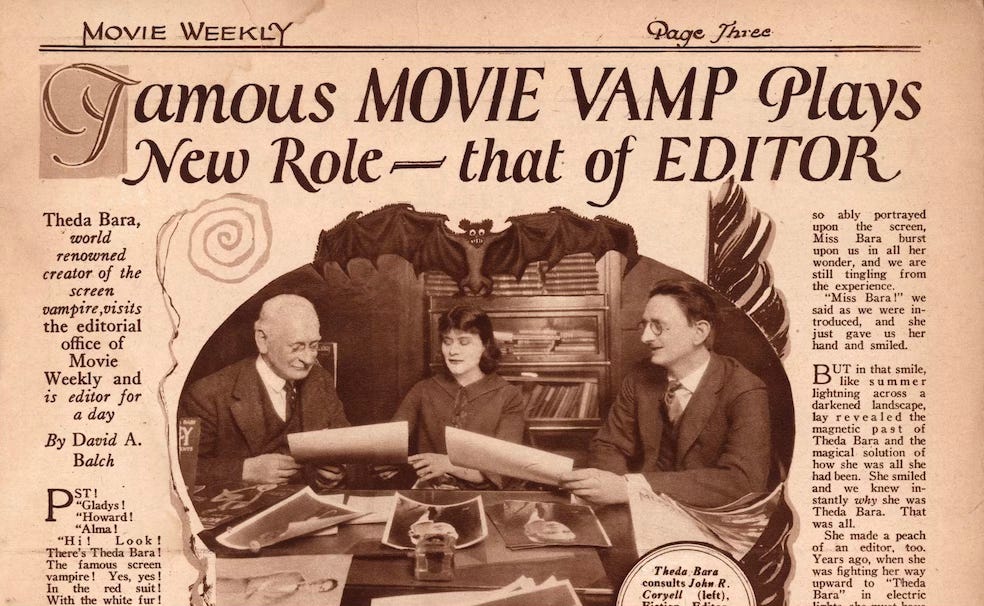

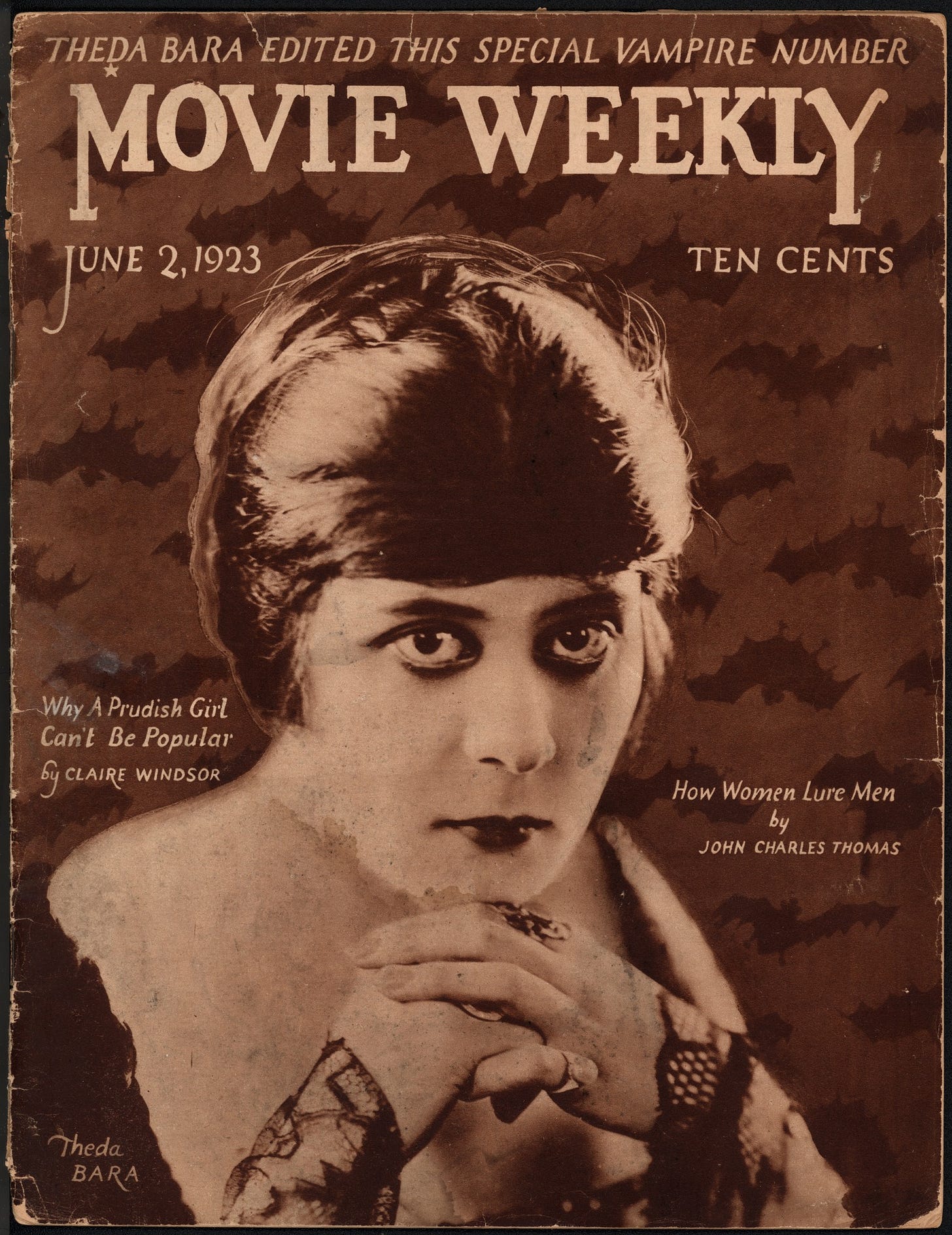

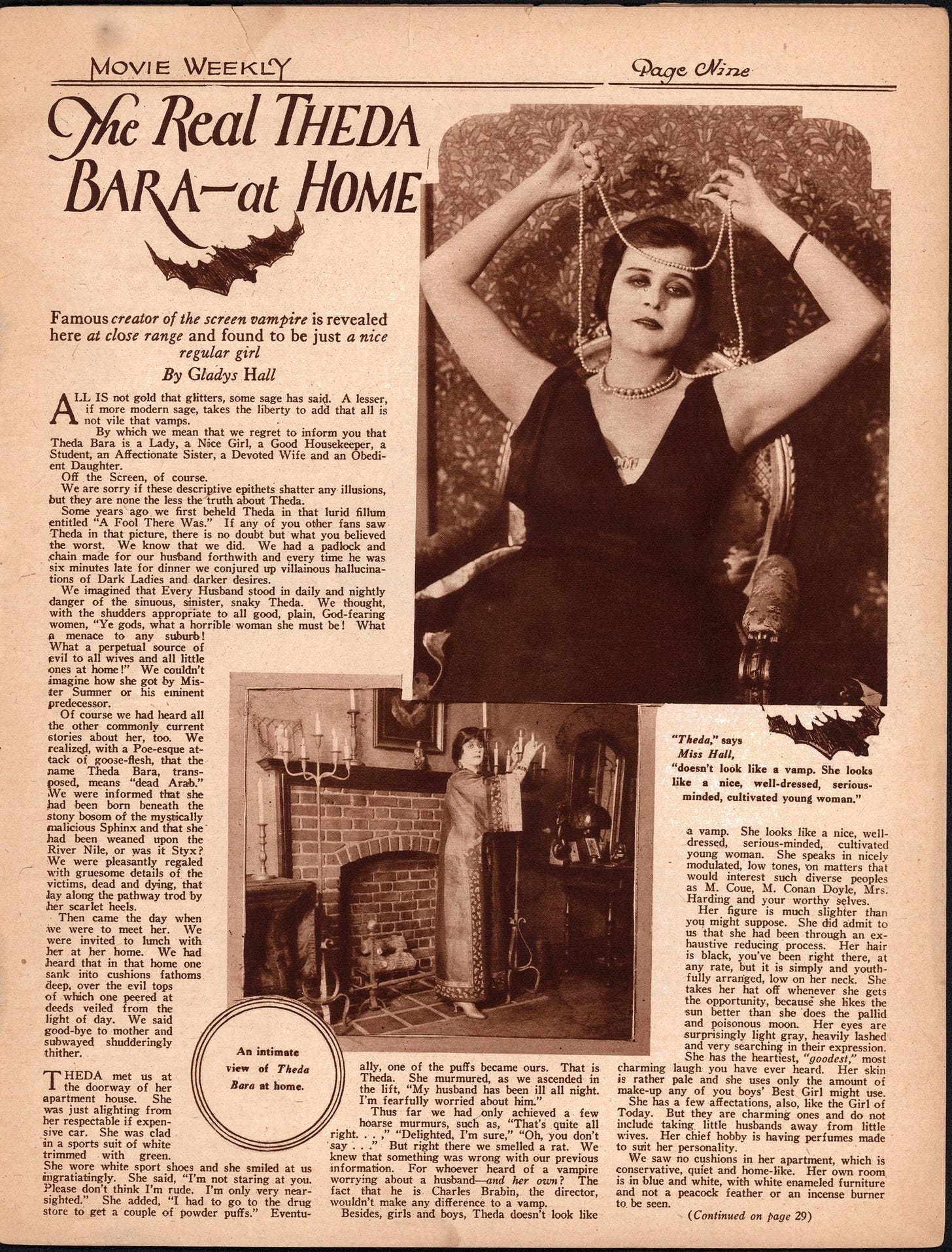

Bara was still an icon, famous for her pioneering star persona even if she wasn’t making hit movies anymore. In June 1923, Bara guest edited an issue of the film enthusiast magazine Movie Weekly.

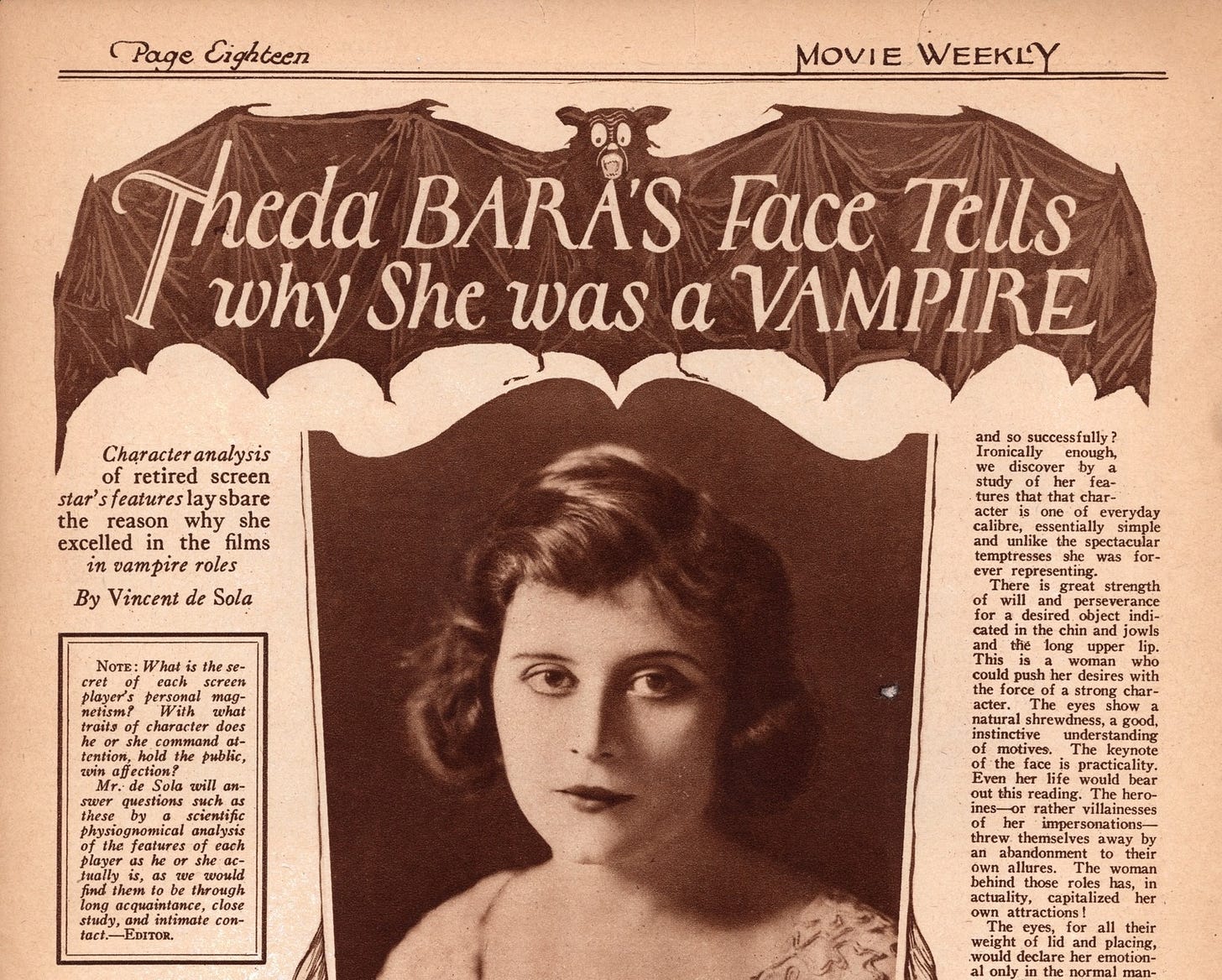

The magazine includes an article titled “Why I Don’t Want Bara to Return to the Screen—By Her Husband.” Bara married Charles Brabin, who had directed one of her films. He continued to direct films, but she retired, and spent the rest of her life as a Hollywood socialite, joking about her scandalous legacy. There’s also an article about her post-film career life, and one in which an amateur character expert explores how “Theda Bara’s Face Tells Why She Was a Vampire.” (I’ve included several pages of this article at the end of this post.)

Sadly, few of Bara’s movies survive. Early silent films were ephemeral and disposable, and after a brief run most silver nitrate reels were melted down for reuse, or to recover the silver. Those nitrate reels were also highly flammable, and most of Bara’s remaining films were destroyed in a 1937 fire at the Fox vault.

The real tragedy is that such a trailblazing figure is virtually forgotten today—not because she lacked impact, but because the medium itself was so new. Film was still finding its form, her acting style feels alien to modern eyes, and most of her work was incinerated like a vampire exposed to sunlight. Unlike her immortal screen persona, our cultural memory of Theda Bara was all too ephemeral.

READ MORE:

But one of them that did survive is her star-making turn as The Vampire in A Fool There Was. Frank 🎥 of Public Domain Movies shares the whole thing here.)

Dan Callahan of Stolen Holiday writes about Bara’s persona and filmography here.

Richard Bluttal of Making History Come Alive has an essay on Bara’s career here.

George Eberhart of Anomalies on Postcards has more backstory on the Kipling poem “The Vampire” and the painting that inspired it here.

Filmmaker Josh Becker writes about William Fox and the origin of Fox Pictures in his newsletter The Crack of Dawn. Read it here.

Dr. C. E. Aubin of Culture Bound writes about the 1937 Fox vault fire that destroyed most of Bara’s film legacy here.

Adam Cook of Long Voyage Home has a fascinating piece about the preservation of nitrate films here.

The audio used in the video clips above are from “The Vamp” by Green Bros. Novelty Orchestra. (1919 Edison Cylinder Recording) You can find it here.

SOURCES:

The full text of the novel A Fool There Was is on Project Gutenberg, and it’s even more over-the-top than you think.

The Man Who Made the Movies: The Meteoric Rise and Tragic Fall of William Fox by Vanda Krefft (2017)

Vamp by Eve Golden (1996)

Theda Bara: A Biography of the Silent Screen Vamp, with a Filmography by Ronald Genini (1996)

An Empire of Their Own How the Jews Invented Hollywood by Neal Gabler (1989)

The You Must Remember This podcast has a great episode on the original vampire. “Theda Bara, Hollywood’s First Sex Symbol” (2014)

And as promised, here is the full Photoplay article about Bara from September of 1915. (Full isue available here.) Excerpts from the 1923 issue of Movie Weekly guest edited by Bara follow.

And here are excerpts from the 1923 issue of Movie Weekly guest edited by Bara. (Full issue available here.)

She was the first true Hollywood sex goddess, and should not be forgotten.

Fascinating read through. Thank you for providing all the old articles - old newspapers and magazines had so much style to them, and the stories are interesting as well.

When researching a different actor who also skyrocketed to fame around that time, I came across a newspaper article from June 10, 1916, including an interview by Miss Bara about her thoughts on the Vampire and her look. I thought you'd find it interesting, so I'll link it here.

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ndnp/dlc/batch_dlc_frontier_ver01/data/sn84026749/00280764334/1916061001/0831.pdf

And additionally, this blurb from the Daily Telegram, West Virginia, June 8, 1916, for her film Sapho (causing so much interest that the local theater extended the showing to TWO days):

The attraction again today at the Robinson Grand will be Theda Bara in the late William Fox release, “Sapho.” The theater has held some very large crowds since it started pictures, but never in the history of the house has the crowd been quite so large as the one which attended last night; in fact the police were called upon to aid the management to hold the enormous crowd back.