The Moment that Defined Esports

Exactly 20 years ago, the frenetic climax of a Street Fighter match helped video games become one of the top spectator sports

The recently concluded Olympics had so many indelible moments: the triumphant return of Simone Biles, Cole Hocker’s stunning upset in the men’s 1500-meter race, Novak Djokovic completing the Golden Slam. Video clips of these unforgettable victories were clipped and shared and compulsively rewatched by people all over the world.

Many professional sports have produced similar moments of drama and spectacle so storied and indelible that they have earned their own nickname. Football has “The Immaculate Reception.” Baseball has “The Shot Heard Round the World.” Basketball has “Larry’s Steal.”

There’s a defining instant like that for esports as well: It’s called “Moment #37” and it happened twenty years ago in a ballroom at California State Polytechnic University. Nowadays, moments like this play out in huge stadiums to tens of thousands of spectators, or are livestreamed on sites like Twitch to global audiences. But esports was a much more niche phenomenon at the time. One of the things that made esports the huge phenomenon it is today was grainy camcorder footage of Moment #37 that was passed around like samizdat among fighting game aficionados.

Moment #37 happened during the third annual Evolution Championship Series tournament, as one of the best players in America, Justin Wong, was facing off against the best player from Japan, Daigo “The Beast” Umehara, on the 1999 fighting game Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike. Wong was playing as Chun-Li, a female character who was prized by players for her kicking attacks. Umehara was playing as Ken. Ken is widely regarded as one of the more boring, plain-vanilla characters in the franchise. But Umehara could perform absolutely amazing feats with him.

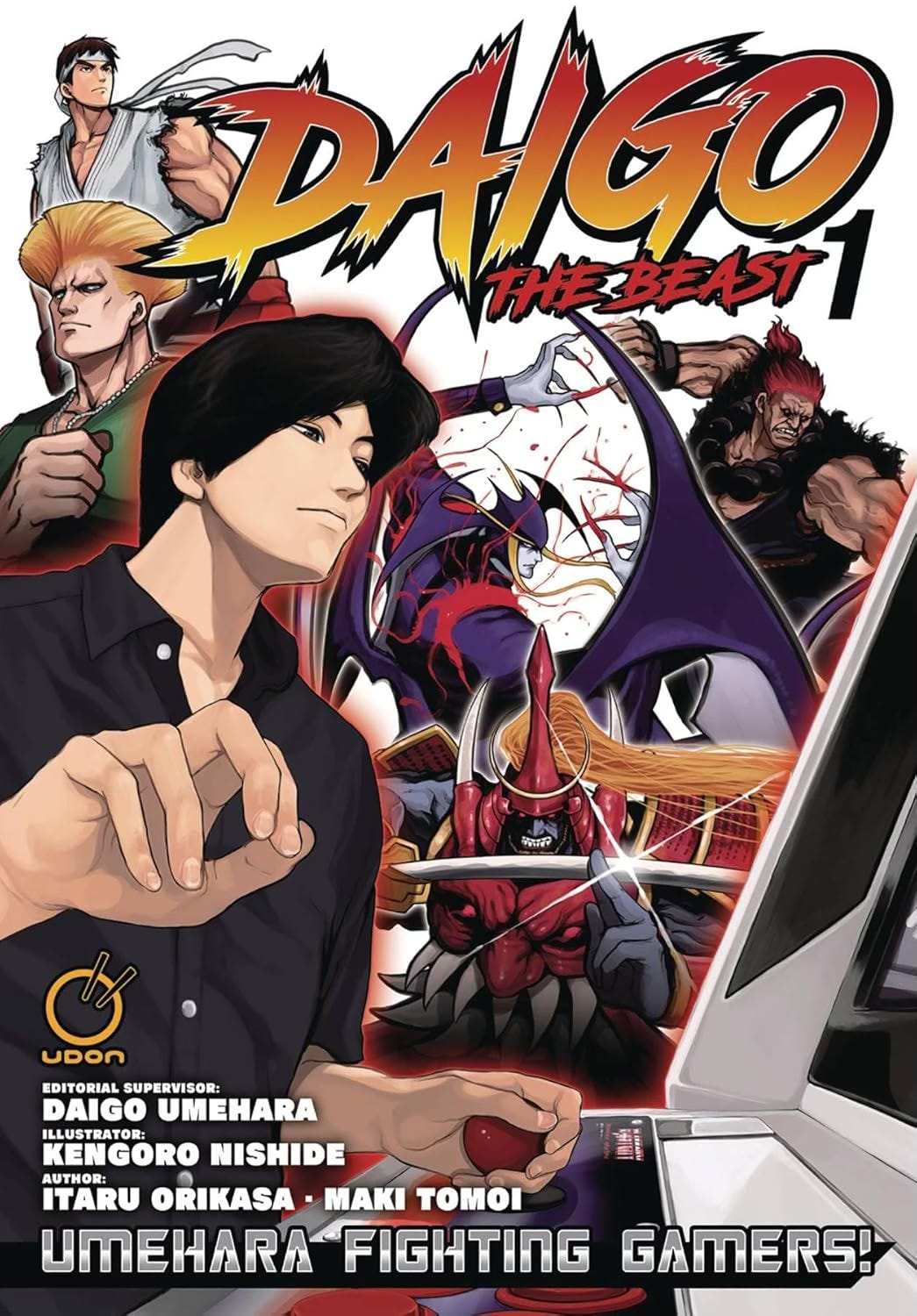

Umehara’s talent, drive, and relentlessness have made him the first superstar cyberathlete in Japan, where he is known as “the god of 2D fighting games.” There is a manga comic that chronicles his gaming exploits,

Umehara had a long-running column in a game magazine, and he published five books. One of them became a best-selling motivational book, The Will to Keep Winning, which claims to impart life lessons from his stellar gaming career that are helpful to a general audience. “Interacting and competing with others, clear win–loss results, the planning and effort needed to excel—these all translate well to issues we confront every day,” he writes.

Umehara has also scored innumerable victories in international events, which have earned him a worldwide following as well as a Guinness World Record for Most Consecutive Tournament Wins. And as the popularity of esports exploded, with audiences and prize purses that are orders of magnitude larger than they were when Umehara started out in the late 1990s, his visibility only increased. He snagged a lucrative sponsorship deal with Red Bull, and he’s a “global ambassador” for Twitch. He continued competing in and winning tournaments until age 41, which is positively ancient in the youth-dominated world of esports. (Imagine Mark Spitz plunging into the Seine to compete in the 2024 Olympics…it’s equivalent to that.)

In his motivational book, which has been translated into English, Umehara explains exactly what fighting games have meant to him. He describes an unpleasant childhood in Tokyo as a detached, irritable, shy kid. He also had a wicked competitive streak. “Losing meant having to lower my head,” he writes. “To me, that was reprehensible. I’d rather die than give up.”

In junior high, he began taking the train alone to arcades. He had discovered his lifelong passion. “The only time I found solace was when I beat someone playing fighting games,” he writes. “I gave my all to gaming, sacrificing my time and my health in pursuit of the win.”

Tournament-level play in 2D fighting games is extremely intense. Players must master an elaborate set of complicated moves for each character, drilling over and over until they can be performed from pure muscle memory. And they must learn exactly how any response from an opponent can interrupt or break any of their moves. And it’s all happening fast – players are literally counting the individual frames of animation, launching attacks and counters at the precise split-second needed. It’s like playing three-dimensional chess at 200 miles per hour. “There’s no time to think about what your opponent is going to do next; thought and action must be nearly simultaneous,” he writes. “If your read is off, you have to grasp the difference between your and your opponent’s intuitions and instantly adjust.”

He is not a showy, crowd-pleasing player. He is laser-focused on the matches, and is famous for being impassive in the face of victory. When he won his first national title at age 15, he was not enthusiastic or jubilant. “Having put in more hours than all the other players out there, being the best felt like the obvious outcome. So when I was handed the trophy, it didn’t excite me whatsoever.”

“The man looks ice cold; you rarely see him emote,” says Patrick Miller, game developer and author of From Masher to Master: The Educated Video Game Enthusiast’s Fighting Game Primer. “He has a great mind for reading his opponent, he understands the framework of a game and how people make decisions within it. He does well in this very Daigo way.”

Before he unleashed what would become known as Moment #37 (a name chosen entirely at random by the Evo organizers, it turns out) Umehara actually got off to a weak start in the match. The American was “turtling,” using his character Chun-Li conservatively, chipping away at his opponent’s life gauge. It was the antithesis of Umehara’s aggressive approach, and as video of the match proves, it was quite effective at getting under his skin.

“This is rare footage of Daigo actually angry,” noted the match’s commentator Seth Killian, who would go on to work for Street Fighter publisher Capcom and develop many fighting games. “Justin’s turtle-style now on the verge of putting Daigo down.”

The game went down to the final round of the final match. Whoever KO’d their opponent one final time would be the winner. Wong clobbered Umehara again and again until his life gauge was reduced to a single pixel-width. One more hit of any kind would mean game over.

“I remember feeling the pressure as I watched my life gauge dwindle, thinking this might be the end,” writes Umehara in his book. “But when he had me in that corner, I entered into a Zen-like focus, prepared to do whatever it took.”

At that moment, Wong unleashed a seemingly unbeatable move, an explosive flurry of 15 lightning-fast kicks so powerful that each dealt damage even if you blocked it… and Umehara was a single hit away from defeat. Things looked grim for The Beast.

But Wong did not realize that he had been baited into this position.

Umehara had sensed that his opponent was eager to end the match with a flourish. Wong could have simply let the clock run out and won, but the god of 2D fighters did everything he could to goad the American into trotting out his big move.

Umehara saw an infinitesimally small opening to catch his opponent off guard and stage a comeback. All he would have to do was parry each of the kicks instead of blocking them. Parrying is a high-risk high-reward defensive maneuver in Street Fighter III that prevents a player under attack from taking damage if they lean into a blow at the precisely perfect moment. The “parry window” is four frames of animation – about seven one-hundredths of a second.

And that superhuman feat of timing wasn’t even the most difficult part.

Umehara would have no advance notice of when Wong’s attack had been initiated. He would have to intuit the precise moment that the furious onslaught began. “He essentially had to make the first parry before the move started,” says Miller, who was one of the thousand or so fighting game fans in the audience that day. “And if he mistimed just one of them, it’s over and he’s lost.”

Somehow, The Beast pulled it off.

He parried kick after kick after kick after kick after kick after kick. Then, before Wong had time to initiate another move, Umehara dispatched him with a devastating super attack known as Shippu Jinraikyaku, or “Hurricane Swift Thunder Leg.” In just a few seconds, Umehara had gone from near-certain defeat to total victory. (You can watch the whole three-minute match in the embedded video below, or jump right to the climactic moment by clicking here.)

“When I came back to myself Chun-Li was down,” The Beast writes in his book. “It wasn’t until then that the screams from the crowd finally reached my ears.”

“Unbelievable,” shouted commentator Killian, his voice cracking with excitement as the enormity of the reversal sunk in. “Daigo with the full parry, and then combo for the win… It’s madness! It’s unadulterated madness!”

The crowd was beside itself. They had initially been pulling for their countryman Wong. But after this astonishing display, they leaped to their feet to cheer for Umehara. “This match was no longer about Justin the American guy versus Daigo the Japanese guy,” says Miller. “It was about how humans are capable of incredible things, and how this video game is one of the things that lets us express this.”

Miller says that there were elements of mastery in that moment that he didn’t fully grasp until years afterwads. Killian would later note that the perfectly timed parries and combos were not the most impressive feats that Umehara performed in Moment #37. “The real strength of the play was mental,” he has said. “It was such an incredible read of the situation and such an incredible move of Jiu Jitsu to take someone’s advantage and use it against them in such a brilliant way.”

“The match made a big wave online, reaching more than 20 million views worldwide,” writes Umehara. “And so, the name Daigo Umehara became known across the globe.”

The obsessive attention that his singular feat continues to garner leaves Umehara somewhat nonplussed. If there’s a central takeaway from his motivational book, it’s that the dedication and discipline and rigorous practice required to stay on top are far more important than any individual victory. “I’ve never deluded myself into thinking that I had mastered games, or that I’m some kind of prodigy,” he writes. “But am I confident in my ability to keep winning? Hell yes.”

“Daigo always was a little surprised that it was such a big deal for us, that it left that kind of impact,” says Miller. “For the people in the American fighting game community that were there to witness it, it was the most significant day of our lives. For Daigo, it was Sunday.”

A version of this piece originally ran on rollingstone.com.

Fantastic piece! You captured the drama of that moment 20 years ago perfectly.