The TV Cowboy Who Built the Modern World of Merchandising

75 years ago, Hopalong Cassidy became the first superstar of the small-screen. Then he built a gargantuan product licensing and sponsorship empire.

Every holiday season, we’re all treated to an audio reminder of the Great Hoppy Craze of 1949. Next time you hear Perry Como or Bing Crosby crooning that old chestnut “It's Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas,” pay attention to the lyrics:

It's beginning to look a lot like Christmas

Toys in every store…

A pair of Hopalong boots and a pistol that shoots

Is the wish of Barney and Ben

Barney and Ben weren’t alone in their desire for licensed Hopalong Cassidy footwear. In midcentury America, it seemed like every single kid wanted clothes, toys, and knickknacks branded with the face and the moniker of the famous small-screen cowboy known as “Hoppy.”

You might think that the preposterously excessive licensed merchandise bonanza as we know it today only dates back to the era of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles or Transformers or Star Wars. But it actually kicked off 75 years ago when an over-the-hill B-movie cowpoke became the first superstar of the small screen.

Half a century before the Schwarzenegger comedy Jingle All the Way poked fun at the commodification of Christmas, parents were already spending December 24th battling tooth and nail over the last piece of Hopalong Cassidy merch on department store shelves

The character Hopalong Cassidy originated in a series of Western novels that appeared in the first years of the 20th Century. Those were followed by 66 B-films cranked out between 1934 and 1948. “Hoppy” was portrayed by the actor William Boyd. He wasn’t a particularly skilled horseman. He didn’t sing in the saddle like Roy Rogers or Gene Autry. He had a string of sidekicks over the run of the films, and they were mostly interchangeable. The only thing remotely singular about this sarsaparilla-swigging buckaroo was that he wore black instead of standard good-guy white.

What turned Hopalong Cassidy into a TV icon was Boyd’s unflagging belief in the character. When the studio felt that the B-Western series had run its course in 1943, Boyd produced the final 12 films himself on shoe-string budgets. And when there was no longer a market for even those cheaply made oaters, the actor sold his ranch and his car and poured his life savings into buying the rights to the Hoppy films, the character, and all associated merchandising.

Boyd was no John Wayne, but his understanding of the value of intellectual property was way, way ahead of its time.

Boyd finalized the deal just as the TV medium was hitting critical mass. The price of sets was plummeting, the number of broadcast networks was expanding, and the number of households with TVs was quadrupling year-to-year—from a million in 1949 to 20 million in 1952. The new medium was starved for content to fill all of those broadcast hours.

Hopalong Cassidy became the first TV cowboy in the summer of 1949. The library of old feature films that Boyd owned was immediately sliced up into broadcast-length chunks and aired over and over again in prime time while a new TV series was rushed into production. The old films and the 52 new episodes cranked out over the next three years caught rival Western movie stars, many of whom had much higher profiles, flat-footed. Hopalong Cassidy quickly became a household name, and Boyd quickly became obscenely wealthy.

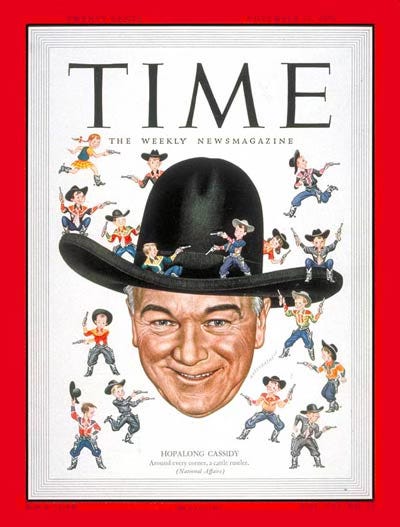

“Among all the U.S. enterprisers who devote themselves to titillating the unripened mind, none has succeeded as Hoppy has, both with his under-age customers and the thousands of manufacturers, retailers, and advertising men who hawk his wares,” wrote Time magazine in a 1950 cover story. “Last week 63 television stations were pumping out his old movies, 152 radio stations were carrying his voice, 155 newspapers were printing his new Hopalong Cassidy comic strip, and 108 licensed manufacturers were turning out Hopalong Cassidy products at the rate of $70 million a year.”

Licensed merch wasn’t a completely new phenomenon. There had been a profusion of tie-in toys for Mickey Mouse and Superman in the 1930s. And as the movie A Christmas Story demonstrated, one young man was willing to do anything to get his hands on a Red Ryder Carbine Action 200-shot Range Model air rifle back in 1939.

But the scale and the scope of Hopalong-mania were unprecedented. Part of the reason was that the increased immediacy and intimacy of the TV medium forged a deeper connection. But the main reason is that this craze coincided with the post-WWII economic boom. People had more disposable income, consumer choice had become much broader, and manufacturing processes were more flexible and able to respond more quickly to trends.

Starting in 1949, Hopalong Cassidy’s kisser was stamped onto hundreds and eventually thousands of products, including the first lunchbox to bear a licensed image. The tin food receptacle was available in red or blue and had a simple paper decal of Hoppy pasted on the side. Within a year, it led to a twelve-fold sales increase for its maker.

Hopalong Cassidy was the first pop culture craze to truly lasso the hearts of the Baby Boomers. Adults in an increasingly urban and industrialized America were astonished by the intensity of their children’s newfound passion for the Wild West.

Time magazine noted:

The kiddies exhibited a leaping enthusiasm for the new and massive doses of entertainment offered by video. Overnight, almost every little boy & girl in the nation had become a cowboy; in those carefully metered periods which they spent outdoors between programs, they saw cattle rustlers around every corner. They were not the first U.S. children to indulge in make-believe about the Old West. But they were the first to catch the fever simultaneously from coast to coast and to demand such splendid arms and accouterments.

Children with impressively styled cap guns and bejeweled double holsters (many tied to their thighs to facilitate a fast draw) were so commonplace that those without them seemed a little underdressed.

The array of branded playthings on offer was dizzying. This virtual museum exhibit hints at the variety of toys. But the Hoppy craze went so far beyond toys…

In the early 1950s, a kid could sleep in a room decorated with Hopalong Cassidy wallpaper, wearing Hopalong Cassidy pajamas, on a Hopalong Cassidy bunk bed. They could wake up and switch on a Hopalong Cassidy lamp atop their Hopalong Cassidy nightstand, listen to a Hopalong Cassidy radio while they washed their face with soap shaped like their hero’s horse Toppy, dress head-to-toe in Hoppy-branded cowboy gear pulled from their Hopalong Cassidy dresser, eat breakfast with Hopalong Cassidy branded plates and bowls and utensils, and then grab an armload of Hopalong Cassidy school supplies and pedal off to school on a Hopalong Cassidy bicycle.

Many of the foods that Hoppy-besotted youths consumed also had sponsorship deals with the TV star. There were cookies and candy bars and peanut butter and Sugar Crisp cereal, all branded “Hoppy’s Favorite.” But The American Heritage Center, which houses Boyd’s papers, notes that the most common deals were for staples like bread, tuna, and dairy products. Boyd had his standards—he reportedly declined one endorsement deal because he disapproved of chewing gum, and he claimed to have turned down innumerable offers from products that he deemed shoddy or unsafe.

Time wrote that the actor “has an almost evangelistic attitude about his success. He discusses himself in the third person—as ‘Hoppy’ or ‘this character’—and seems to feel that he has retapped the same deep vein of American character which made the Old West, and that it is both his fate and his duty to strengthen the fiber of U.S. youth…When a department store manager suggested that crowds which had come to see Hoppy were duty-bound to buy something in return, the people's friend promptly punched him in the nose.”

“For folks who sell things to the nation’s small fry, he’s the greatest godsend to come down the train in the memory of man,” The Wall Street Journal wrote. “Manufacturers are standing in queues awaiting permission to tack his name to their merchandise for juveniles.”

“Hopalong was the Michael Jordan of his time,” says Byron Price, executive director of the Cowboy Hall of Fame. “It was the most successful merchandising campaign there had ever been.”

In the summer of 1951, the 80-acre Hoppyland amusement park opened in Venice, California. (Four years before Walt Disney launched his own titular theme park in Anaheim.) It offered 20 rides, a baseball diamond, horseshoe pits, and even “a man-made mountain stocked with goats,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

Hoppyland closed its doors in 1954, and the whole cowboy craze fizzled before the end of the 1950s as kids’ attention increasingly turned to sci-fi. Boomers set aside their spurs and cap pistols and cowboy hats for toy rockets and ray guns and space helmets. (This cultural shift is recapitulated in the first Toy Story, with the Sheriff Woody stuffed doll elbowed out of the spotlight by the Buzz Lightyear plastic action figure.)

Still, William Boyd continued to profit from the Cassidy cash cow that he never relinquished the rights to. Despite giving a large chunk of his fortune to charity, he had nearly $10 million in the bank when he rode off into the sunset in 1971. You can still watch all of the episodes of Hopalong Cassidy through various streaming services, but Boyd’s real legacy is the more than 2,500 products bearing the Hoppy name.

And if your cranky octogenarian great uncle mocks you for driving all over town trying to find your kid a Chicken Dance Elmo or a Barbie Dream Besties doll, you can console yourself knowing that when the old coot was young, he probably whined and moped for weeks until his poor parents broke down and bought him a pair of Acme Hopalong Cassidy Cowboy Boots and a Hopalong Cassidy Gold Plated Repeating Cap Pistol.